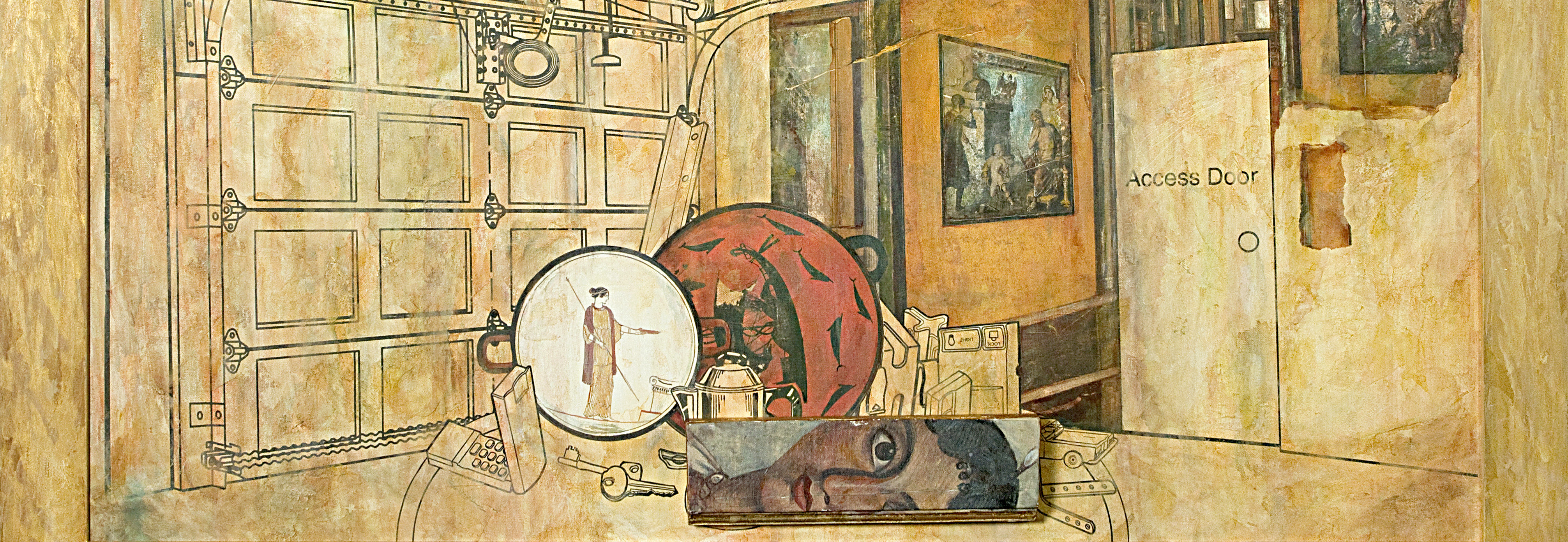

Elena Sarni, “Access Door” (2012)

Elena Sarni, “Access Door” (2012)

A Word or Two from the Lord

At the time of the book’s printing, the author of the text was twenty-two years old. He considers himself a decent writer in the primitivist style and currently works in the Vyatka Cheka.

The Young Worker

A hot-blooded, hulking fiend of a young worker will break all of Papa’s windows, knock over Mama’s canapé, whack Brother round the ear, frighten the life out of Sister, who—ah!—will remember it for the rest of her life, he’ll flatten the eunuch cat, find me in my room, push me in the stomach, tear my lace, hoist me up, plant me like a nut on a bolt and carry me away from here—Lord, oh Lord, make it happen! He is a furious red hammer. Yes, yes—I’m a Socialist. Long live the proletariat. And Papa is a swine. I hate him, the bourgeois. So thought Valya, the daughter of the chief engineer, in her room at 11 o’clock in the morning.

Dogs with Wings

We were walking across the bridge and imagining excitedly what kind of wings each breed of dog would have:

A German shepherd has eagle wings;

A dachshund has small wings; it flaps them often like a duck (the dachshund is the duck of the dog world);

The poodle is assisted in flight by its ears; on its sides it has an extra pair of wings, just as tousled and silly;

A fox terrier has the wings of a beetle, and during flight it is the only dog not to bark, but to emit a distinctive hum;

A pug has wings like ladies’ fans;

A pointer has elastic elegant ovals;

Bichons have small pink tongues and their eyes are hidden from view; the wings of a bichon are two neat little curd cheese pastries;

When greyhounds fly the girls go crazy; a greyhound’s wings are like those of the archangels on the canvases of the Italian renaissance;

Huskies and spitz dogs have invisible wings—they have lived too long among sorcerers;

It is not hard to imagine how a bulldog flies: desperately waving its negligible round winglets and itching to push off from some other dog flying nearby. The other dogs won’t grumble though, they all love bulldogs. We decided that a bulldog would need a propeller;

And a spaniel flips through the air from stomach to back. He is his own propeller, and has no need of wings.

The bridge was long, warmed throughout the day, and the dogs with our wings flew over it.

The Girl and the Woman

Angel Dima told me this story.

General Krushilov, who lived in Kiev, had a daughter called Mashenka. She was an adorable elf of a girl with shining eyes and a heart as pure as a white begonia. Mashenka was barely seventeen, and her parents only ever called her mouseykins, squirrel-wirrel, and Minkie, and for Christmas and Easter they gave her long knitted socks filled with nuts. Mashenka would stay in the city all year long, then in the summer they would send her to the dacha of an old lady-cousin of Papa’s for the holidays.

This was how it had always been, and so it was this summer. Only this time Second Lieutenant Knysh, a real cockroach, who was recuperating after being wounded, took up lodgings near our dacha ladies. He took Mashenka for walks in the meadow and invited her to his orchard to help pick the cherries.

Mashenka left Kiev a charming and modest girl, and returned a fiery and strident woman, gawping crazily from side to side. She’d walk about the house like a bulldog on its hind legs, bedecking herself in shawls and poking her father in the stomach, saying, “Aye-aye!” while flaring her nostrils and winking. For days on end the general and his wife would dash from room to room, taking turns to clutch their heads and cry, “Dearie me!” Or, shutting themselves away in their bedroom, they would gaze into each other’s eyes for ages, holding hands and listening through the window as outdoors Mashenka stamped her feet and laughed hoarsely, explaining something to the coachman.

Big Saturday Love

On Saturday, no matter where we’ve been invited, and whatever the weather, Anya and I know that today our big Saturday love is to take place. What’s that? It is five hours between the sheets in the middle of an empty house on a day of rest. Ah, is it really five hours? Well, we don’t keep an eye on our watches like those Englishmen.

We work hard, and our life is a series of long, cold days, but the moment we got married, we decided firmly that our number one family tradition would be big Saturday love. Everything is always rather dreary, and the winter here is not getting any milder—God forbid, we wouldn’t want it to. We just tell our friends not to visit us on Saturdays—after all, they have no way of telling when our big Saturday love might start and end.

Nelly

The dear thing, she hasn’t worn glasses since that incident. They shattered to dust on the step of the tram. It’s common knowledge that horseless trams are powered by the devil, and Nelly got on one without crossing herself.

Nelly did have a ticket; she wanted to get off at the corner of the Evangelists Church; “Two cakes at the patisserie, to be sure, I’ll get two, not one,” thought Nelly, placing her foot on the step, when all of a sudden a millimetre from her ear boomed the deafening, bearlike roar: “Show us your ticket, Miss.” Here’s what happened next: with bells ringing in her ears, Nelly saw the devil in the form of the tram driver. He stood within a hair’s breadth of Nelly and blocked her path with his arm, he was missing a tooth, his forehead was burnt and peeling, and he had only one eye, bang in the middle of that burnt forehead, I believe. The devil smiled sneeringly. “A-a-ah, too tight-fisted to buy a ticket!” hissed his flunkies from all around. That very moment Nelly’s glasses cracked once and for all – the devil dimmed into a blur, the lenses shattered, and the frame slipped from her little nose and fell in their wake. It seems Nelly did show the devil her ticket, because soon she was standing in the street, having forgotten about the patisserie, without her glasses, unable to move from the spot, because a horseless tram is powered by the devil, and you have to cross yourself, or better still, spit on the rails and say “begone,” and then there are those airyplanes and watch out one might fall on your head, and there’s also a black quail that’s roaming the city stealing children.

The Bread Proletariat

Of all the proletariat the best is the bread proletariat. It is made up of people sprinkled in flour and smelling of the happiest truth that comes out of the earth. Their life is not so sweet as their cheeks and hands might be, but you must admit, a bread factory is better than an iron foundry or a coal pit. Of course, man’s exploitation of man is to be found everywhere, and our floury toilers often have the eyes of beguiled children. But that’s why the enthusiasm and special dedication of a man who can make a tasty twisted bread ring in the revolutionary ranks make the bread proletariat the most sweet-smelling column of all.

Aunties

How I loved them—my mother’s adorable sisters and Auntie Sasha, the sister of my father. They played with me, took me for walks and told me all sorts of silliness. Now I know that they were my childhood sexual experiences. But in fact I was a sexual experience for them too. It is no accident that they sometimes got changed in front of me, though it’s true, they would turn away or tell me to turn around. They went bathing with me, in swimsuits, of course, but oh how they used to catch me in the water, throw me in the air, teach me to swim! I learnt to swim with most tender teachers, but I also remember how my arm or leg would unexpectedly knock against something unmentionable.

Who asked, “Do you love me?” And who said, “Give your auntie a kiss”? Who picked berries with me in grandmother’s garden in a loose-fitting smock dress and, bending to reach the lower branches, flashed their breasts and dark nipples? They took me around the little town on a bicycle and suddenly played up: “Time for you to pedal.” And I pedalled with all the steamy spirit of my six, or nine, or twelve years, and then they all went and got married. Perhaps I was heartbroken, although perhaps not—after all, I’m not a girl. In any case I lived in a different town. And I was taken to my aunties by my parents for one of the summer months, and then brought home again.

Gangstress Lena

How many red heroes she slayed! How she’d whistle and spit in the face of the next martyr. And she could shake her curls and whip off her belt with its huge buckle. Her trousers would slip—whoops!—the whole rabble would guffaw.

How skinny and slight she was, Lena’s thugs carried her everywhere: to her horse, or to church, or to the bushes when nature called. Lena would sit in the bushes, with her gangsters all in a semicircle—swords drawn—in salute to Lena.

She yelled and didn’t wash properly, but they loved her all the same. She used to execute the red heroes herself. She’d whistle and spit, she’d say, “What starts with ‘d’ belongs to me.” Then bang in the forehead from her Mauser! “What starts with ‘d’ belongs to me”—that was her favourite saying.

Engineer Slavyanov

Nikolai Gavrilovich Slavyanov, head of the Perm state gun factories, sailed on the steamship France to the World’s Fair in Chicago to receive a diploma and gold medal, awarded for inventing the electric arc welding of metals using metal electrodes. It was the year 1893. The ocean was quiet, and the sea monsters rocked lazily on its surface without a thought of gobbling up the Russian inventor. The middle of the ocean, thought Slavyanov, and he chuckled into his beard. He remembered how in Perm his wife had said to him, “Kolya, bring a white parrot from America, we’ll call it Anton.”

In Russia no doubt it was now the dead of night. Slavyanov could not sleep; standing on deck, he was wondering: Why is she so keen on the name Anton?