I was having a drink on the balcony of a friend’s apartment in Brooklyn last April when I fainted, flipped over the railing and fell two stories onto a parked vehicle and thence into an asphalt parking lot some fifteen feet below. With respect to this incident, two schools of thought have emerged among my friends and professional acquaintances. The first is that it was a very lucky thing that I fainted before I fell, since if I’d been conscious I might have braced myself or stiffened my neck and been seriously injured; instead I plummeted with unwonted grace and walked away fairly unscathed. The other position is that if I hadn’t fainted I would never have fallen to begin with. I’m committed to neither view.

Since then, I’ve developed a powerful interest in the areas of collapse, heights, luck, and death, and my thoughts on these subjects have been colored by a number of chance encounters following the incident. About four months later, I was standing on another balcony—also in Brooklyn, also drinking—having a conversation with the writer Durga Chew-Bose. She told me that, as a teenager, she was in the Copper Canyon, Mexico, crossing a rope bridge. “Five or six people, heavier people, had crossed before me. And by luck I stepped on a broken plank and fell into a dry rock riverbed about thirty feet below.” So badly injured was she that when we met again for drinks another four months later—nearly a decade after her fall—she was again having dental surgery to repair the damage.

Did she feel that she was lucky in having survived, I asked her, or unlucky in having fallen? Not certain: “The nurses kept saying, You’re so lucky to be alive. I said sure, but I was just being polite to them.” What about the moral aspect? Did she feel her experience gave her any special insight into her own condition, existential or otherwise? Again, not really: “I don’t value my experience in any special way,” she said. “The closest I’ve come to understanding death is grieving.”

A month before I’d talked with Durga the first time, and three months after the fall, I was having another conversation, this time with the artist Kenny Scharf. We were sitting on a porch in East Hampton, and neither of us was drinking. Scharf, who was debuting a new show with gallerist Eric Firestone, has spent most of his working life dangling off the sides of tall structures, chiefly bridges and scaffolds but also power stations, monuments, apartment buildings, factories, billboards, viaducts, radio towers, and lampposts, all to create his signature graffito-art caricatures. He is usually stoned when he does this. “I think it regulates me, makes me normal—I like to do lots of sport things smoking weed,” said Scharf, who was stoned at the time.

He continued, “I’m afraid of falling, I’m just not afraid of heights. If it doesn’t feel like I’m going to fall, then I’m not afraid, but if I feel like I’m going to fall, then it’s scary.” Scharf paused and pulled at his joint. “I did fall once recently,” he said. “Off my bike. I got a hematoma on my hip and they had to remove it.” Jesus, I thought to myself, why we don’t just cling to the ground in terror all the time? I was not, incidentally, smoking marijuana as I was thinking this, and have not done so since the night of the fall. I suspect the small amount I’d inhaled earlier that evening contributed to my passing out.

Gravity is unique among the fundamental forces of the universe in so far as no one quite knows how it operates. It may be governed by a subatomic particle called the graviton, or it may be a nothing but a sort of cosmic fiction. There’s a Nobel Prize waiting for the person who figures it out, and when they do they will resolve one of the pressing mysteries of science. “One of the curious things is that gravity is actually the weakest force,” says physicist Michael Tutt of Columbia University, who I met in a coffee shop uptown. “Usually people think of it as really strong—it made you fall two stories, after all. But it isn’t, compared to the other forces, and the question is, why?” Gravity, as it turns out, is far less powerful than, say, magnetism: witness the humble refrigerator magnet, able to resist the whole gravitational pull of the planet.

As I explained to Prof. Tutt, I’m trying to understand all this in a thorough, objective way as a means of keeping at bay the lingering horror of my own personal experience. Perhaps a physicist—understanding how weak gravity really is—can somehow see through it? Achieve a kind of enlightened equanimity with the universe, instead of quaking in fear at every precipice? “No, I don’t think of some fundamental calculus,” says Tutt. “The realm of particle physics goes beyond our everyday experience. Dropping an apple, getting hit by a truck, falling off a balcony: that’s the only way we experience reality.” The consolations of philosophy do not apply in this instance: we are all in the same boat, waterfall-bound.

My typical métier—writing about architecture and design for a number of newspapers and magazines—has largely to do with things-that-do-not-not-fall-down. It was in this connection that I recently met Mahadev Raman, who has spent his life keeping things from collapsing. As director of global engineering giant Arup Associates, he’s created complex structures none of which ever tumble headlong into a near-empty parking lot in Williamsburg, destroying the roof of a Chevy Astrovan on the way down. “As a ten year old, I was fascinated by tall structures—I used to climb to the top of electricity cables out back of our house in Zambia,” recalls Raman, whose schoolteacher parents had relocated from India to the former British colony in southern Africa. Although Raman has never been involved with a project that’s fallen down, he’s witnessed the problem firsthand, having consulted post-collapse on structures like the failed New York City construction cranes and the skating rink roof that gave way just before the Salt Lake City Olympics. “Any time there’s any kind of a failure of a system, it feels like a personal defect,” Raman said. His friend Leslie Robertson, for example, remains haunted by the collapse of the World Trade Center, whose structural system he helped devise. Not that Robertson, or anyone else, could have anticipated that kind of strain.

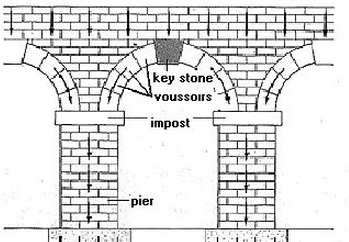

And then too, seen in a certain light, buildings are always falling down: they’re just doing it at an imperceptibly slow rate. Consider the keystone arches in the Corinthian story of the Roman Coliseum (Fig. 1): braced against its opposite, each side of the arch is kept in check by the other, playing gravity off against itself and thereby defying it. That’s some consolation, I feel—that one can play a trick on gravity. (Just try playing a trick on, say, time.) Completed in 80 AD, the Coliseum has withstood eons of being pulled down and down and down and down. Perhaps that is playing a trick on time.

Being a physical coward myself, I’ve never aspired to fool any of nature’s implacable forces, so I don’t know quite why I came in for this comeuppance the way I did. Only a couple months back (five months after the fall, two weeks before the evening with Durga, six after the afternoon with Scharf) I was touring a project with the architect David Adjaye, a new housing development in Upper Manhattan. We were on a top-floor terrace with a very low parapet and a sweeping urban vista beyond it; pointing to the knee-high wall, the designer said, “I wish we could keep it that way, but they’re making us put up a glass partition” to keep people from toppling overboard.

I like Adjaye’s work a great deal—in particular his way of mixing traditional and modern African motifs—but I disagree with him entirely on this point. I’m all for these sorts of regulations, and fully support the work of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. For Chirssakes, if David Adjaye wants to tempt fate, how come he hasn’t gone ass-over-teakettle off a balcony, executing (as reported by witnesses) a perfect Olympic pommel horse maneuver, body vertical and hands grasping the railing for an impossible moment before letting go? “I love these open construction elevators,” said David Adjaye, as we descended the fifteen floors of the new high-rise and I clung desperately to the metal cage of the lift.

It’s been a lifelong struggle. When I was seven or so, some well-intentioned Montessorians diagnosed me with a learning disorder based entirely on my terror of high places. I was enrolled in a physical therapy program where smiling collegians with lanyard whistles coaxed me up ladders and across monkey bars. It didn’t work: I still hate heights. Danny Forster is an architect and host of The Discovery Channel’s Extreme Engineering for nine seasons, during the course of which he climbed up the sides of such enormous structures as the Shanghai World Financial Center, the Al Hamra Tower in Kuwait City, and the 77-story Central Market Tower in Abu Dhabi. I met him over coffee, two days (incredibly) after I fell. Forster claims there’s nothing to it. “Like they say in the stupid safety lessons, once you’re above six feet it’s the same as a thousand. A fall is a fall. You can die.” So why should I bother worrying? Forster is no less a bespectacled landlubber than I, and he seems fairly unfazed. In any case, I never had a learning disorder. I simply don’t like heights.

On the other hand, perhaps if the physical therapy had succeeded I’d be on TV, telling you all about my falling off a balcony while grasping onto the 2,717-foot-high spike of the Burj Khalifa.

Perhaps, perhaps. Perhaps I wouldn’t have ended up going abroad on assignment for five weeks, writing about a dozen different not-falling-down-yet buildings and generally running myself ragged. I wouldn’t have come back to the States with a debilitating cold and drunk so much Riesling and then, all undaunted, gone over to a friend’s house to smoke marijuana and had a panic attack on their plastically appointed terrace. The attack was precipitated by exhaustion, drugs, alcohol, and the psychic trauma of the then-recent termination of my engagement—the latter being itself a form of falling, a sensation of unarrested motion in space that likewise left one outwardly intact yet somehow deeply altered.

The moment I hit the ground, I popped right up, bleeding from the head and missing my phone and passport which had slipped under the vehicle. I felt instantly better.

✖

“I don’t remember the fall either,” said Durga at the rooftop cocktail party. “I just opened my eyes and everyone was around me. Also, could you stand a little further away from the edge there? Thanks.”

One of the interesting distinctions between Durga’s experience and my own is that while neither of us remember the actual incident, in her case the memory was probably knocked out of her upon impact. In my case, by comparison, my memory was suspended before I fell of the balcony. The film cut out, and when the picture resumed I was lying against what I took to be the back wall of a narrow closet. A closet of rare device, this one, since it went up instead of out. In the brief instant before voices reached me, I created a narrative to explain how I’d arrived there: I had simply gotten very tired and went to sleep standing up in my friend’s closet. The way one does. It was no more implausible in its way than what had happened, which is that I had somehow struck the parked van face first and then slipped into the narrow margin separating it from a concrete retaining wall.

In any collapse, the crowds gather around to gawk until the trained experts appear with calculators. After 7,000 Chinese schoolrooms collapsed following the Sichuan earthquake of 2008, engineers engaged in a frenzied effort to reconstruct (strange word, in context) the process by which they had given way. The results of their investigation, though indicating faulty building practices, stopped short of implicating systematic corruption, after interference by officials of the Chinese government halted the inquest. In Venice, about three weeks after my fall, I saw Ai Weiwei’s installation, Straight, a stack of iron bars recovered from the ruined buildings. The wall text featured a quote from the artist: “The tragic reality of today is reflected in the true plight of our spiritual existence. We are spineless and cannot stand straight.” There but for the grace of gravity, and of parked vans in otherwise empty parking lots, go we. The only meaningful evidence of my impact was the impression in the roof of the vehicle and the side-view mirror knocked off the passenger door.

Everyone snaps to attention when gravity is in play. Pierre Petit walks out onto the tightrope between the buildings of the old World Trade Center, and Jeff Koons dangles a steaming train engine from a crane in Los Angeles, and the German team leaps simultaneously from the high board at the London Olympics. Popular NPR program RadioLab aired an episode three years ago on the topic of falling, but I’ve been reluctant to listen to it since I’ve been afraid it might stir up some sublimated unpleasantness. Which is absurd, since I do not and cannot remember a blessed thing. I cannot reassemble anything of this episode of my life that was almost its last, anymore than I can extract any semblance of meaning from it. Does that make me lucky or unlucky? “Hard to say,” Kenny Scharf told me. “I would say no,” said Michael Tutt. “I don’t endow it with that much meaning,” said Durga. Oh, well.

Or is there more to it than that? A few weeks after our site tour, Adjaye and I met back up in Washington, D.C. to look at another new project of his, the future Museum of African American History on the National Mall. The present site is nothing more than a giant hole in the ground, as builders must construct a concrete envelope for the foundation to keep out the water of an ancient underground river. We stood on the lip of the excavation and peered down the seventy-some-odd feet into the dirt and bristling rebar below, as a builder scaled the sheer wall opposite on a thin ladder, descending.

I watched the small, helmeted, fly-like figure across the void, and all in an instant I felt a strange empathy: a memory not of the mind but of the body, of a suspension in the extremities and of quietly resigning oneself to the elements. This sensation lasted only a moment. But I’m almost certain it was real.