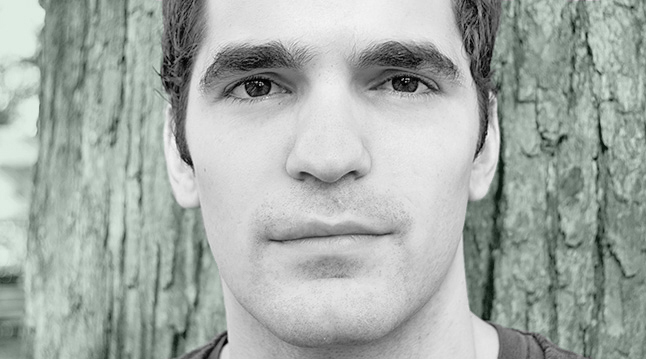

Bennett Sims wrote my favorite novel of 2013.

A Questionable Shape, Sims’ debut, follows two college friends, Mazoch and Vermaelen, on a weeklong quest through a devastated Baton Rouge reeling from a peculiar catastrophe: a zombie outbreak. The friends are on a search for Mazoch’s father, missing and believed undead. The approach of hurricane season looms over them—this week is their last chance to find Mazoch’s father and get him to a quarantine zone before the storms.

Sims’ novel masterfully casts the undead not as instruments of fear, but rather as occasions for reflection: moral and phenomenological gray areas that allow characters to dwell on questions of consciousness, identity, memory, and familial obligation. Narrated in elegant and controlled prose, elaborately footnoted, and rife with allusions to great works in philosophy, psychology, and film, A Questionable Shape is complex, erudite, and profoundly affecting. It reveals him to be a writer of great range, depth, and intelligence, who has only just begun to show us what he has to say.

Sims’ short fiction has appeared or is forthcoming in A Public Space, Conjunctions, Electric Literature, Tin House, and Zoetrope: All-Story. Fresh off a year of teaching at the University of Iowa (after graduating from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop himself), he was awarded the 2014 Bard Fiction Prize, recently given to young writers such as Nathan Englander, Karen Russell, and Benjamin Hale.

In the midst of his move to Annandale-on-Hudson to take up the position of writer in residence for the spring semester at Bard College, I corresponded with Sims over email about his groundbreaking novel and a few of the questions it raises.

—Nathan Goldman

✖

Nathan Goldman: A Questionable Shape has been out for a little more than half a year. It’s garnered excellent reviews, it’s all over best of 2013 lists, and you recently received the 2014 Bard Fiction Prize. How are you feeling about the book and the response?

Bennett Sims: I’ve been pleasantly surprised. I approached the publication process with a fair amount of pessimism, since the novel caters to the hatreds of so many different kinds of readers: readers who hate zombies, readers who hate footnotes, readers who hate plotlessness, philosophy, boredom. I didn’t expect many people to read the book, so the response has been really heartening. The Bard Fiction Prize, especially, is an incredible gift. With that said, I’ve still managed to remain pessimistic: whenever something nice happens, I assume that it’s the last nice thing that will ever happen.

NG: When recommending it, I often describe A Questionable Shape as a “literary zombie novel.” Similar descriptions abound in reviews. Clearly there is much more to the novel than its “literariness” and the fact that its plot involves the undead. But the tendency to summarize the book in this way seems revealing with respect to the novel’s relationship to the current literary climate. What do you think the relationship is between so-called “literary” and “genre” fiction in contemporary American literature? How does A Questionable Shape fit in?

BS: Bleh. I don’t know that I can offer insightful commentary on this. The relationship between ‘genre’ and ‘literary’ is pretty confused right now, and I’m sympathetic with readers who are impatient to just deconstruct that dichotomy and move on. What seems to be happening is that more and more literary writers are deciding to explore traditionally generic subject matter. It’s not uncommon to see reviews of the latest ‘literary mummy novel’ or ‘literary space opera,’ and if you were to ask critics to clarify exactly what they mean by ‘literary’ here, they’d probably provide one of two descriptions: either a stylometric checklist (lyrical prose; psychological depth; complex characterization) or a genealogy of influence (‘It’s the kind of mummy novel Lydia Davis might write’). As a reader, I tend to find the second class of description more helpful: it gives me a better idea of what the book might be like, and it doesn’t reinscribe as many insidious biases about genre (with that first description, on the other hand, you end up implying—whether intentionally or not—that run-of-the-mill mummy novels somehow lack lyrical prose and complex characterization).

A lot of contemporary conversations about genre seem to be spinning their wheels in these biases. Psychological realism was the dominant mode of literary fiction for so long in America that our intuitions about subject matter are deeply entrenched: whereas stories about human beings make for serious works of art, stories about time travel or vampires or apocalypses make for formulaic entertainment. So whenever critics describe something as a ‘literary vampire novel,’ they can seem to be using ‘literary’ as a synonym for ‘good’ or ‘aesthetically ambitious’: as in, ‘It has vampires in it, but don’t worry, it’s well written.’ This has the unfortunate effect of reducing ‘genre’ to a Judge Potter-y pejorative, which people reserve only for the vampire novels that they don’t like. As a result, genre readers are forced to continually advocate on behalf of their own canons, pointing out the existence of other well-written, aesthetically ambitious vampire/mummy/space-opera novels (as well as the existence of generic [i.e., shallow or formulaic] suburban-adultery novels). Complicating all this is the fact that ‘genre’ and ‘literary’ have also come to designate structurally distinct culture industries, with parallel publishing institutions and networks of prestige. So if two authors write about time travel, it might matter in the short term which of them attends Clarion or an MFA, appears in Lightspeed or The New Yorker, is reviewed in Strange Horizons or The New York Times, wins the Nebula or the National Book Award: all this could determine which community of readers they’re marketed to. That seems to be where we’re stuck these days, which is why it still feels natural to describe A Questionable Shape as a literary zombie novel. ‘Literary’ marks both its stylistic affiliations and the institutional channels through which it was produced. For what it’s worth, I usually find myself describing it to people as ‘the kind of zombie novel Nicholson Baker might write.’

NG: What kind of mummy novel might Lydia Davis write?

BS: Tutankhamun Is Indignant.

NG: This is a major cultural moment for zombies: Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, The Walking Dead, Zone One, World War Z. Why do you think that is?

BS: I’m not sure why zombies appeal to the culture right now. Historically, they were one of the first monsters in the 20th century to really explore the problematics of apocalypse: unlike site-specific creatures (the werewolf on the moor, the ghost in its mansion), zombies tend to spread virally, infecting entire cities and nations overnight. So it’s possible that zombie narratives provide a unique screen for projecting cultural anxieties about societal collapse. And it’s true that, with each generation of films, the ‘zombie apocalypse’ has remained allegorically customizable, tailored to different eras’ apposite disasters: nuclear fallout, globalization, pandemics, industrial pollution, climate change, overpopulation and resource scarcity, bioterrorism, mass migration, and so on. If this is a major moment for zombies, it might be an index of our own generation’s disaster mentality.

On the other hand, individual zombies are just as compelling as crowds of them. Any given zombie is a threshold figure, suspended between various oppositional concepts: between life and death; consciousness and unconsciousness; free will and automatism; memory and forgetting. This is the kind of creature that philosophers have in mind whenever they write about zombies: something that looks and acts like a human being but that is secretly ‘all dark inside,’ without any inner awareness. Taken individually, then, zombies seem to embody our culture’s uncertainties about subjectivity, about what the limits of selfhood are. If your mother lacks consciousness—if your mother’s memory is erased—is she still your mother? Some version of this question is posed in almost every zombie film. In Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), one boy insists—paradoxically—that ‘his mother is not his mother’; and in Shaun of the Dead, a character exclaims, ‘She’s not his mum anymore! She’s a zombie!’ Possibly the first formulation of this anxiety appears in Euripides’ The Bacchae, when Pentheus is being dismembered by Agave, who’s too frenzied by Dionysus to recognize him: ‘She fell upon him, and he…shrieked at her: “Me! It’s me! It’s Pentheus, Mother. Your son! You are my mother!…I’m your son: don’t kill me!”’ Like the apocalypse, this subjective dimension of undeath seems to be a flexible metaphor, adaptable to different cultures’ concerns about consciousness: intoxication and ecstatic self-forgetting for Euripides; compulsive mass consumption for Romero. Dementia, Alzheimer’s, brain death. Put simply, zombies may fascinate people now because minds do.

NG: To what degree, when you were writing the book, were you thinking about it as a “zombie novel”? What effect, if any, did that have on aesthetic choices and how you talked about (and continue to talk about) the book?

BS: I always conceived of the book as a ‘zombie novel without zombies.’ I wanted my characters to be able to argue about undeath without ever having to actually run from or fend off the undead. This meant that the zombies in the novel had to be marginalized, both socially (they’re quarantined) and dramatically (they rarely appear in scenes). Since the characters don’t feel threatened by the undead, their conversations are free to shift away from the apocalyptic logistics of most zombie fiction (‘How do we survive?’ ‘How do we kill them?’ ‘How do we know who’s been bitten?’) to a more passive fascination with zombies’ creatureliness (‘What do they remember?’ ‘Are they conscious?’ ‘What is it like to be them?’). For the most part, this decision also seems to have shifted people’s conversations about the book itself, which has been gratifying.

NG: You’ve said in previous interviews that many of the ideas in A Questionable Shape are derived from your undergraduate thesis on the use of zombies in critical discourses—philosophy, anthropology, psychoanalysis, etc. What changed in your thinking about zombies and their significance as what had been a critical thesis transformed into a novel?

BS: What changed was less my thinking about zombies than my feeling about them. The thesis did have a narrator, a first person plural ‘we’ that issued aphorisms about the undead (the opening line of the novel is vestigial in this sense: ‘What we know about the undead is this…’). But the thesis’s narrator wasn’t a fictional character: it was just a critical or exegetical intelligence. All it had to do was conduct close readings of zombie films and block-quote philosophical texts. It never had to go looking for an undead family member, or draft a list of places where its reanimated body might return to, or order potentially contaminated food from a diner. Nor did it have to ask the messy ethical questions that the characters in the novel have to: like, ‘What is a son’s duty to a terminally unconscious father?’ or ‘What legal or political rights should unconscious bodies have?’ My experience of the two projects was that my fictional narrator had a more complicated inner life than my critical one, so the novel forced me to feel my way through the day-to-day emotional implications of undeath. Writing about zombies like this, I found that I ended up sharing in the full spectrum of my characters’ reactions to them: awe, pity, philosophical curiosity, fear, morbid fascination, mortal envy. That’s what I mean when I say that my feelings changed. Compared to the novel, the thesis just had a much narrower affective bandwidth: all I felt about zombies while writing it was philosophical curiosity.

NG: The narrator spends a lot of time meditating on the consciousness and phenomenal experience of the undead. His thought frequently has recourse to thinkers such as Wittgenstein, Freud, Heidegger, and Viktor Shklovsky. In this way, A Questionable Shape is a philosophical novel not just in the sense that it raises philosophical questions, but also in its active engagement with the philosophical tradition and in the fact that the narrator thinks in the language of that tradition. What does fiction that is explicitly in conversation with a philosophical tradition have to offer philosophical discourse?

BS: I can probably piggyback on my last answer for this one. When novels narrativize philosophical problems, part of what they’re doing is demonstrating what it would actually feel like for someone to live out those concepts. They’re like laboratories for applied philosophy. What might it feel like to be an embittered Russian outcast ranting against utilitarianism in the 19th century? Dostoevsky’s Notes From Underground. What might it feel like to stage some of Baudrillard’s simulacrum scenarios in modern-day London? Tom McCarthy’s Remainder. What might post-apocalyptic solipsism feel like, if you thought you were literally the last person left on the planet and were struggling to describe your surroundings with the epistemological precision and propositional exactitude of Wittgenstein’s Tractatus…? David Markson’s Wittgenstein’s Mistress.

Of course, different novels engage with philosophy in different ways. I’m somewhat reluctant to describe A Questionable Shape as a ‘philosophical novel’ because its own mode of engagement seems so superficially allusive. If the narrator sees something that reminds him of Wittgenstein or Heidegger, he’ll quote them in a footnote, but their ideas generally aren’t being dramatized with real rigor. I guess the one contribution that the novel makes is to show how someone might draw on these thinkers in order to understand undeath, in a world where zombies actually existed. That’s its big insight: that if walking corpses started shuffling around, Agamben and David Chalmers and Euripides and Freud and Heidegger and Hitchcock and Shklovsky and Tarkosvky and Wittgenstein would all read pretty differently.

✖