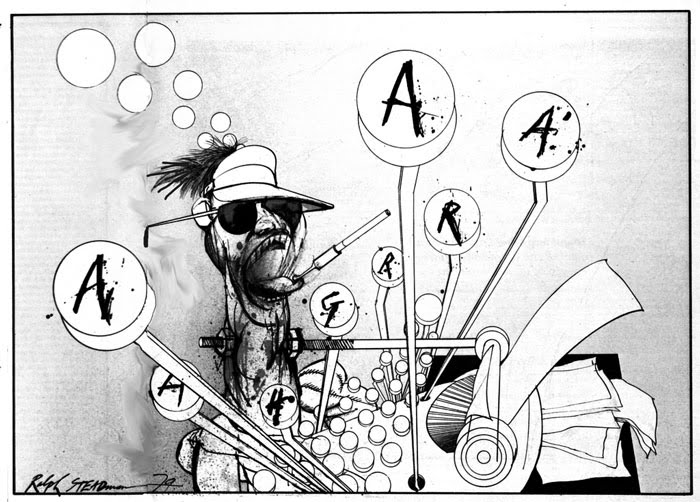

A Ralph Steadman illustration.

A Ralph Steadman illustration.

In the following, senior editor Samuel Burr gives a short note on graphic journalism, as preface to Lucy Knisley’s “The New Life of the Comic Book”. Read her work here.

+

“Print is dead.”

This was proclaimed, and loudly—shouted from the newspapers, scrolled in oversized, bold font on the televisions, chanted by the collective media in choreographed synchrony…

I was a journalism student at Northeastern when the economy crashed. In December of 2007—dead smack in the middle of my studies at Northeastern University—it was announced that America was in a recession.

Print is dead.

As I was preparing to graduate (my last course was in December of 2008), “the financial crisis of 2008,” had begun in earnest, continuing conservatively until late 2009 (though many would of course argue that the crisis stretched significantly further than the year and a half the American government stated). By the summer and early fall of 2009, we had eased, or careened, as it were, into the worst recession since The Great Depression.

Print is dead.

Journalism schools began to shut down; no refunds were given. My own alma mater shuffled their curriculum, but offered no advice whatsoever to graduating journalism majors preparing to enter into a marketplace rocked by the most significant financial crisis in nearly a century.

Print is dead.

Then, on August 18th of 2010, a strange happening: the New York Times came out with an article titled, “What Is It About 20-Somethings?” penned by Robin Marantz Henig. After casually dismissing my generation as essentially stunted emotionally, Ms. Henig, disregarding both circumstance (the economy) and sense, insisted that the source of our generation’s difficulties in regards to finding employment was not environmental and historical in nature, but rather came down to our developmental psychology. Talk about missing the point. But Ms. Henig pressed even further down this fatuous, misleading path, playing with semantics along the way: “The 20s are a black box” ; “We’re in the thick of what one sociologist calls ‘the changing timetable for adulthood.’” ; “…emerging adulthood.” Then she had the gall to validate her false premise with incongruous if not simply inane metrics, all tailored to support this shameless equivocation-laden filler of an article:

“We’re in the thick of what one sociologist calls “the changing timetable for adulthood.” Sociologists traditionally define the “transition to adulthood” as marked by five milestones: completing school, leaving home, becoming financially independent, marrying and having a child. In 1960, 77 percent of women and 65 percent of men had, by the time they reached 30, passed all five milestones. Among 30-year-olds in 2000, according to data from the United States Census Bureau, fewer than half of the women and one-third of the men had done so. A Canadian study reported that a typical 30-year-old in 2001 had completed the same number of milestones as a 25-year-old in the early ’70s.”

Almost all of my contemporaries were infuriated. In fact, most would agree it was one of the two worst articles the Times has published in the last decade (the other caused a war). But, at the very least it was a spur: “What is it about 20-somethings” gave me the motivation to turn a 20,000 word short story I had written about youth living in 2010 Manhattan into a 90,000 word novel, which might someday go to the printers—as long as the increasingly pervasive shrieks that “print is dead!” are in fact just coming from parrots.

If “What Is It About 20-Somethings?” got printed in the New York Times, and affected so deeply so many of my contemporaries, then print never died. And more importantly, our generation has improvised, and quickly. New mediums have emerged. Gone are the days of filler stories like the aforementioned piece, or at least the days our generation will pay any attention to them.

Evidence of this is a new form of journalism, which is edging its way into the mainstream—graphic journalism. Signs that this form of journalism is very much on the ascent have glowed bright neon for a while now. Ralph Steadman’s illustrations combined with Hunter S. Thompson’s text in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas laid some ground work. Still, it was not quite graphic journalism. An influence, certainly. A foundation, not exactly. Graphic journalism mixes coverage of real events of a broad scope (investigative journalism, event coverage, even critical examinations and first person accounts of travel, media, et cetera) with illustrations, as Lucy Knisley’s current piece “The New Life of the… COMIC BOOK” demonstrates. Artists with rooted interest in graphic journalism at this early stage, such as Ms. Knisley, are not only pioneers, but they are progressively shepherding this new form of journalism towards a wider audience. When it will truly “arrive” is up for debate, but the mainstream (though it is this form’s inevitable destination) has no purchase on graphic journalism from an artistic standpoint. So, enjoy graphic journalism now, as these roots are as plentiful as they are pulchritudinous.

One of the fascinating elements of this genre is the manner in which the illustrations that break up the passages not only leaven the text as artistic evidence of sorts, but also allows one’s mind to engage the subject and go places that one does not when reading a text-only article. The pauses engendered by the pictorial breaks recall the experience of viewing art in general. That affinity between the calm act of encounter and the pause the reader must take in the midst of reading is a curious and important one.

But how these two experiences—encountering illustrations in graphic journalism and viewing art in a traditional gallery setting—differ is perhaps most interesting. When you meet with an illustration in a work of graphic journalism, you are in the midst of an unfolding narrative that is not your own; you have a story; you’re already implicated in another world by proxy of the text. When viewing art in a traditional setting, however, you may go into the gallery thinking about your daily to-do list: perhaps worrying about your laundry, your girlfriend, your life—you go in thinking of something, and so, in an important sense, your mind is not free. Because the artistic act is doubled in graphic journalism—because you first give yourself into a written narrative, and then to a visual one—your mind is free (or at least, freer). Your mind, perhaps subconsciously, absconds from the quotidian, from your lamentations of the past and your presentiments of the future. It is more possible to live in the moment, however fleetingly, because you have here, in one contained genre, two modes of escape, two accomplices. And so, in an interesting and deeply compelling way, this newest instantiation of the doubled art experience opens new avenues to the imagination, new ways of engaging the senses.

Notice the illustrations in Ms. Knisley’s piece: how they not only emphasize a point, but also free your imagination, permitting you to explore the topic as you see fit.

Then return to the text; investigate further. And when the next illustration arises, retreat. Repeat.