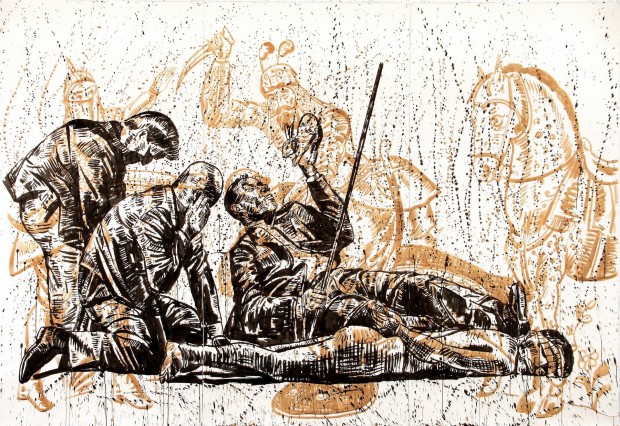

- Inspector’s Scrutiny

- Hasty Retreat

- Invasion

- The One Who Sees What Is Hidden

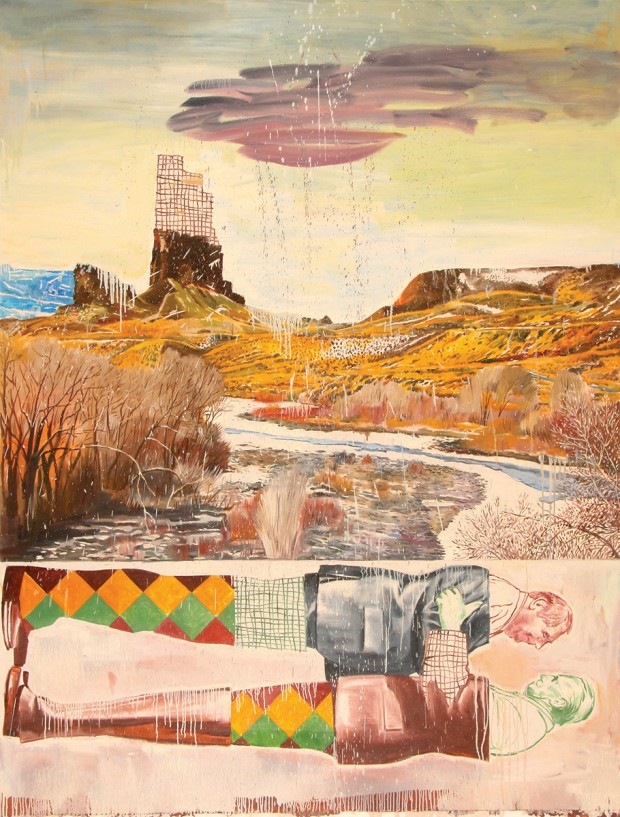

- The Accident

- Time to Pray

- Let Me Describe It To You

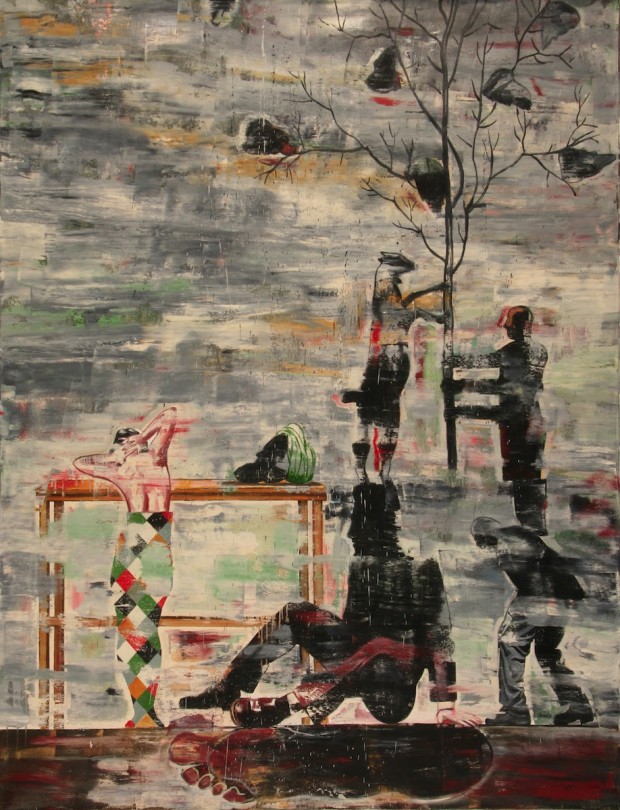

- Last Summer Night

- The Shadow of a Cloud

- High Jump

- Caught in the Game

- Dancing

- Intriguing Gesture

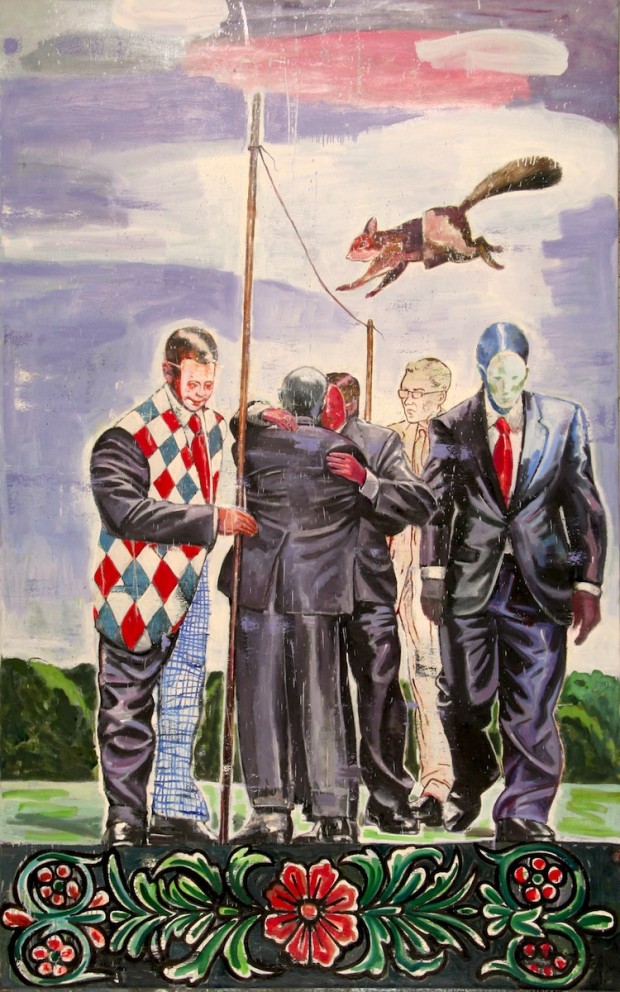

- Chasing the Butterfly

Iranian artist Nicky Nodjoumi’s large scale oil and ink paintings explore dynamics of power and violence. Nodjoumi marries re-contextualized photographs from the news with everyday objects and pregnant iterations of ancient and universal images. His most recent exhibit was the inaugural show Chasing the Butterfly at the Taymour Grahne Gallery. Below, Nodjoumi reflects on form versus content and the cryptic significance of string.

—Alma Vescovi

American Reader: Your work is often described as political commentary, even though the specific kind of engagement associated with the word “commentary” (e.g. the discursive exploration associated with op-eds or documentaries) doesn’t seem applicable to images. There’s an aspect of “on the one hand, on the other hand” at which the written word excels but with which the image struggles. Would you describe your work as commentary?

Nicky Nodjoumi: I hesitate to do that. I think what we’re missing here is the visual aspect of the painting. If you say commentary, we look for the comment, we look for the words. There’s a narrative in the painting, but commentary is really more political. Most of them have a critical point of view, but it’s visual, that aspect of it is much more important than anything else. What I like to do is to make such powerful paintings that the image reflects some feeling—you feel that image, you see that image, you experience that image, that’s the difference. If you want to emphasize the commentary, you have to say “visual commentary.” That probably comes closer to what the visual situation is.

AR: Do images have a longer shelf life in the brain than words do?

NN: Hopefully. I like to think if the image is strong enough it will stay longer because you will kind of feel it, it will stay in the unconscious mind.

AR: Iranians have a long and complicated history with the concept of whiteness—before 1935, Iran was still called Persia until Reza Shah changed the name to Iran in an attempt to fortify ties with Nazi Germany by declaring Persians “Aryan.” The figures in Chasing the Butterfly have features as easily associated with the British and Americans, who ran such unwanted interference in Iranian politics and perpetrated the violence depicted in the paintings, as with Iranians themselves. Looking at your work, viewers can’t always be confident they know who they’re looking at. Is this intentional?

NN: Yes, it’s a conscious intention to not pigeonhole, so that you see only Iranians or Americans in the paintings. There is a kind of universal situation, that you can apply it to any place. In one painting, the two men are actually Afghan, and I put them in a situation where you can read it any way you want. I took the photo and deformed it, to get the identity out of them, that way it becomes something else. It’s not real anymore, they don’t exist anymore in that situation. I don’t think any Iranian would identify with them, or any American, in fact, it’s just a kind of human being, but they have a recognizable suit. Most of these paintings are critical of both societies, Iranian and Western.

AR: Are they the same criticisms?

NN: With a twist. The problem is people. When they come into power, no matter what, they do bad things. The paintings are generally about people in power, it doesn’t matter what country. They are demagogues, they are hypocrites.

AR: It’s interesting to see so many horses, long-standing residents of war paintings. There’s a strange duality to a horse in battle; when carrying a charging cavalryman, they seem to represent the finer aspects of war, the depictions which make it seem like a big manly picnic. But when a horse falls in battle, it can bring home with enormous force the surreal nightmare of such organized violence; their immense size adds to the intensity and their innocence feels the more shocking since we know they are often beyond all rescue and care.

In the largest painting in Chasing the Butterfly, Inspector’s Scrutiny, a fallen horse dominates the front and center of the painting, with the same insistence on anatomical accuracy that typifies the military horses of the Western canon. In the background, two grey horses, still standing, seem to be fighting their own battle in a much earlier period, imitating the fluid ink lines and attention to detail found in the art of medieval Middle Eastern empires. In Taking the Horse for a Walk, a chestnut mare trots obediently along led by a man in a suit. Finally, in Dancing, a pale horse lives behind an ink drawing of a man, reminding me of the stooped head and slightly cramped position of a bronze plaque from the 6th-century Persian Achaemenid Empire. Can you talk about the variety of horses painted in the canvases, and the decision to include them along with more contemporary, familiar military tools like nightsticks?

NN: In Inspector’s Scrutiny, I was trying to have this huge something, animal, something that is at the same time powerful and innocent, as you said, that duality. Again, my conscious or unconscious was looking for something to represent people, or represent a country. So I want them to really strong, I want them to be really innocent. Not innocent in terms of being naive, but innocent in terms of being clean. That’s one reason I use the horses. In Inspector’s Scrutiny and Taking the Horse for a Walk, they’re a little bit bigger because I put them in a situation that is larger than normal. I want them to look stronger, but that strength is in conflict with the group of men. We are hoping that if he gets up, the strength will demolish everything. If not, that ladder behind the picture is for a place to hang the horse. It’s a metaphorical situation, its not real, most often it’s a kind of narrative that you make up. I like to have drama in the painting, even though I cannot articulate clearly what the situation is.

AR: What’s going on with all the string? There’s some kind of string or rope in more than half of the paintings in the series.

NN: It’s a kind of artistic vehicle for me to play with. I can put figures in a situation where I can play with it and it also has a metaphorical meaning, a political meaning. You can tie someone with a rope, you can hang someone with rope or string, so you can do a lot with this, with the meaning, it’s not doodling. So I’m using it first as merely artistic, if you don’t look at the meaning of it. All of the paintings have many of these combinations. One side is trying to find a new way to paint, to have different elements that help you bind together all of these meanings, and the other side of it is the meaning of the painting. The string creates a different form in the painting, then it adds to the meaning. So this is a kind of back and forth playing with the form and meaning.

AR: Your style seems to use some of the best techniques of Pop art for very different ends. Pop art addresses a familiarity with certain images so complete that they pass into the brain unchallenged or undetected, like the chairs and ladders present in your paintings. But your paintings feel like a departure from the Warholian culture that makes those pervasive symbols and references the topic itself. Why do these very familiar and banal objects keep making an appearance amongst images of brutality and injustice?

NN: One reason is to make the narrative of the painting complete. By that I mean sometimes they work as an element of decoration, or sometimes as a means to another meaning, and that’s the difference from the Warholian culture. I use it as a decorative element to complete the paintings—it’s a compositional thing, it’s color. I don’t think it’s any easier to process a political painting when there are more familiar images in it, and maybe it’s my fault because I want to confuse people, or I want to confuse myself. I want to make some painting that’s a little bit different from others and I want to have narrative and drama in the painting. It becomes more complicated when you put all these multi-meaning images in one painting, so I’m consciously aware of it and I know a lot of people either don’t like it or it confuses them, but I’m not going to come down on that. For me, when I put them there, I know it’s helping the painting so that’s enough for me, I’m not thinking what happens afterwards.

✖