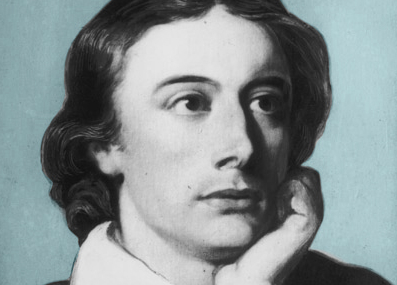

John Keats’s poem “Endymion,” one of the more obscure in his literary canon, tells the story of a shepherd who yearns, dreamily, for a lost beloved while gazing into the bright moon. Keats was self-conscious at the time of the poem’s publication in 1818, prefacing the work with an apology for his artistic purgatory in which “the soul is in a ferment, the character undecided, the way of life uncertain, the ambition thick-sighted.”

The work was savagely denounced in contemporary literary circles. John Gibson Lockhart, writing in Blackwood’s Magazine, went so far as to call the poem an “imperturbable driveling idiocy,” and ended his contemptuous review by suggesting that Keats return to his original occupation as an apothecary. “Back to the shop,” Lockhart wrote, “back to plasters, pills, and ornament boxes.” In the following letter addressed to his publisher, Keats wrestles with the fall-out from this harsh blow.

Hampstead, 9 October 1818

[To James Augustus Hessey]

My dear Hessey—

…I begin to get a little acquainted with my own strength and weakness.—Praise or blame has but a momentary effect on the man whose love of beauty in the abstract makes him a severe critic on his own Works. My own domestic criticism has given me pain without comparison beyond what Blackwood or the Quarterly could possibly inflict—and also when I feel I am right, no external praise can give me such a glow as my own solitary reperception and ratification of what is fine. J. S. is perfectly right in regard to the slip-shod Endymion. That it is so is no fault of mine. No!—though it may sound a little paradoxical. It is as good as I had power to make it—by myself—Had I been nervous about its being a perfect piece, and with that view asked advice, and trembled over every page, it would not have been written; for it is not in my nature to fumble—I will write independently.—I have written independently without Judgment. I may write independently, and with Judgment, hereafter. The Genius of Poetry must work out its own salvation in a man: It cannot be matured by law and precept, but by sensation and watchfulness in itself—That which is creative must create itself—In Endymion, I leaped headlong into the sea, and thereby have become better acquainted with the Soundings, the quicksands, and the rocks, than if I had stayed upon the green shore, and piped a silly pipe, and took tea and comfortable advice. I was never afraid of failure; for I would sooner fail than not be among the greatest—But I am nigh getting into a rant. So, with remembrances to Taylor and Woodhouse etc. I am

Yours very sincerely

John Keats.

FURTHER READING

The full text of “Endymion.”

Lockhart’s review in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine.