Shaw writes to the New York theatrical manager F. C. Whitney. Baron Trenck, a comic opera, has just opened in his newly acquired theatre. Shaw gives advice to Whitney about Arnold Daly, a producer who had brought several of Shaw’s plays to an American audience—talented, but a bit unpredictable for Shaw’s taste.

My dear Whitney

I see that Daly is filling the papers with rash announcements of performances of my plays which will never come off. Do not let him commit you in this way: I cannot prevent him from calmly explaining wonderful plans of campaign to me as if all my plays belonged to him; but I have most carefully avoided committing myself to anything beyond the production of Arms and the Man. And he always assumes that I am dealing with him; whereas the real centre of the business situation is you and nobody else.

As I see the situation, it is something like this. If Daly fails in London, you will, I presume, have to drop him like a hot potato. However, a failure in Arms and the Man may be put out of the question as practically impossible. Suppose, then, the production is a showy first-night success, and brings him a sheaf of good notices. It will be a very serious matter to risk that success by producing a play like Candida, in which he wants to play a stripling of 18 who is supposed to be the nephew of an English peer. The accounts of the American performance which people have given me have been very different; but roughly speaking, the enthusiastic accounts are the American accounts, and the more critical one English. In particular, the people who saw Granville Barker in the part could not stand Daly at all. Daly himself is confident that he can sweep London off its legs by his Eugene; and if it were a case of neck or nothing I should let him have his chance. But when his appearances as Eugene may possibly spoil his success as Bluntschli, and cannot in any case add much to it; and when, furthermore, it would involve engaging another leading lady (Ellen O’Malley would have to play it instead of Miss Halstan), I conclude that we had better let it alone. On the other hand, The Man of Destiny, which exactly suits Miss Halstan (she was the original Street Lady), could be played without a single extra engagement; and I believe Daly could play Napoleon more effectively than it has ever been played before in London. In fact, he would produce the effect of making a success of a play which has never been successful before, whereas in Candida he might quite easily do the reverse.

As to You Never Can Tell, that is asking me for too large a sacrifice. Daly has not the least notion that in letting him have Arms and the Man for 6 weeks at the tag end of the season when it was just becoming ripe for a big revival, and Loraine was very anxious to do it, I am doing as much as he can reasonably expect from me—not to mention this three weeks producing, which, coming on top of Fanny’s First Play, has put a serious strain on me, both physically and financially. To ask me to throw away You Never Can Tell on top of it is beyond all reason.

It therefore comes down to this: that there will be only two Shaw programs: Arms and the Man and The Man of Destiny. I take it, however, that you want to take Daly back to New York as a big artistic proposition in the highest class of modern drama. To achieve this, you must trot him out here in plays by some other author. To a certain extent, a success in my plays does not count: it goes too much as part of the Shaw boom. If Daly could produce, say, two plays by other authors, one being Ibsen and the other Strindberg or Tolstoy, or one of the newer English writers, then he would really have a good stock of plays for America. You must bear in mind that in America You Never Can Tell and Candida are quite stale: he has played them to death there, and to return and begin with them over again would simply make people yawn and stay away. He must have something new from London. Arms and the Man will pass, because he played it only a few times, and apparently did nothing with it; but The Man of Destiny will be no use, as he squeezed it dry in New York: I am suggesting it for London only because we must allow him one appearance in a Shaw part that is not, like Bluntschli, actor-proof. But if he goes back to New York with 3 London successes, all modern and high-class, and only one of them stale Shaw, he will be all right to jump into the leading position which now seems to be vacant there.

There is one other thing for you to consider. Daly has, as you know, been taken up by Tyler (Liebler) and other managers; but they have never been able to hold him: he has always broken away after just a few weeks; and this is, I suppose[,] the real reason why he lost the grip he was just getting on the American theatre with my plays. On this account there is no use in our making arrangements very far ahead. If you and I do any more business, it will have to be more or less hand to mouth where Daly is concerned, because it is impossible for either of us to calculate whether you will be on speaking terms with him next September or not. Immediately he gets a success, there will be no holding him. I do not blame him: he has the qualities of his faults as well as the faults of his qualities; but still, blame him or not, he is what he is, an entirely incalculable person for six weeks ahead.

Perhaps you had better not shew him this letter, as it might upset him uselessly. But you might impress on him that he must not make announcements on your behalf, and that he still has to make his success. From the course of the rehearsals, I have no misgivings about a thoroughly successful first night; but still, you may as well rub it into him that he must conquer London before he hoists the flag.

You need not bother to answer this just now, unless in what I have said above, I have completely mistaken your intentions as to running Daly in the future.

I infer from the difficulty in getting your theatre for rehearsals that you are trying to alter Trenck. I should not if I were you. Alterations never do any good. Either persevere and force it on the public as it is, or else scrap it promptly. You cannot really alter a thing of that size enough to make the difference between success and failure.

Mrs Granville Barker is very anxious that you should go and see Fanny’s First Play. It is really amusing––considering who wrote it. Shall I tell her to send you a box?

yours faithfully

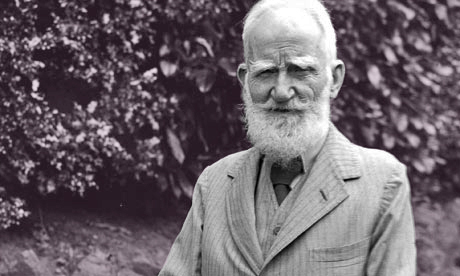

G. Bernard Shaw

FURTHER READING

A mistaken report informs Arnold Daly of his own suicide.