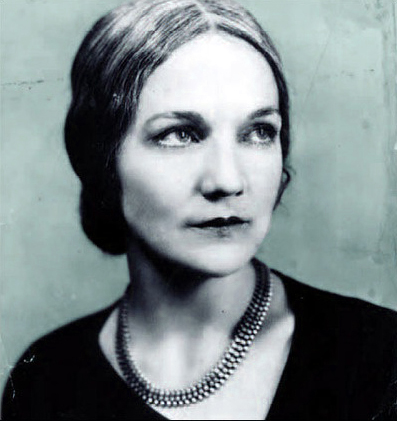

In 1931 Katherine Anne Porter won a Guggenheim fellowship, in part due to the great critical acclaim she received for Flowering Judas (1930), a collection of short stories. The fellowship initiated a five-year long excursion through Europe, allowing Porter to spend time in Berlin, Basel, and Paris. This voyage was the inspiration for her novel Ship of Fools (1962). Below, Porter discusses the challenge of finding time to write while attending to domestic obligations. She had married Eugene D. Pressly two years prior, a consul who was working at the US Embassy in Paris. While living there, Porter worked on a biography of Cotton Mather and a short novel she called Promised Land. Neither of these works were ever finished.

[70 bis rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs] Paris

June 9, 1935

Darling Caroline:

Your letter, dated one month less four days ago, arrived yesterday, which I think must be a modern record for transatlantic crossing. We are in the midst of the Pentecost holidays, such an important feast that my Sylvie, who is Arlesienne, goes home to her family for three days. She takes also Easter, of course, Ascension Day, Bastille Day, Christmas, and Three Kings’ Day, and All Souls’. It occurs to me that this officially rationalistic France is as bound by religious holidays as Mexico. Anyhow, our little chore in the Foreign service does this for us: We get all the American as well as the French holidays; but mostly for me they mean, and so does Sunday, that I get stuck in the kitchen and the dishes do pile up. Just the same, this morning we pulled ourselves together and went to a little village an immense rose garden just coming into bloom. Oh at least a million roses, far too many, really. I should prefer about a half acre, with a dozen varieties very carefully chosen and tended. Some of those heavy dark red roses we used to have, some fine shell-pink-beige tea roses, Gold of Ophir, Gloire de Dijon, several climbing kinds, and a hedge or two of wild roses, and the whole thing surrounded by a carefully clipped wall of cape jessamines. I can see it, I know just how it should look. Some day I may even have it.

Ford, you know, is always praising the French by contrasting them with the benighted Germans and English who are just wild about nature, saying the French never know the names of flowers…As usual, he is talking through his hatful of prejudices, and either doesn’t know what he is talking about or doesn’t give a damn…The French may not care for nature, but God, how they love a tree or a bush or a plant or anything they can set in the earth and train on a trellis and watch grow…They may not like nature, but they love a city full of leafage and fountains and birds. The whole town is just now like a garden…

Our own private estate has just about got out of hand. The Virginia creeper is closing in on Gene, he can hardly see out of his own windows, the ivy has gone wild and lilac trees think they own the place, the chestnut is dense and shady as an umbrella, and there must be some hardy pruning around here come next clipping time…I send you a few pretty bad snapshots. The camera is really no good, how I miss my Rolleiflex…It’s a hot drowsy afternoon, and I hear Gene over in the atelier playing Scarlett’s “Good Humoured Ladies” on the gramophone. Pretty soon we’ll have some sherry. And I shall make hot biscuits for dinner. And that is about what living is like around here. I saw the Italian show—and saw things I shall never see again, I imagine—we went to hear Landowska play a gorgeous program of music of the time of Shakespeare, (What Music) and saw four thrillers at the Grand Guignol, and I went twice to the Horticultural Show at Cours La Reine, and that is a whole springtime of activity. For the rest, I just sit about in the intervals of small errands and household chores and think constantly that if ever, ever in this world I get two hours and a half to myself I’m going to finish one of those forty short stories I have lined up, or Cotton Mather, or the novel…None of this may ever happen unless I manage to distribute my time or grow claws. In “legend and memory” I am stuck right now in the middle of the history of great-aunt Sallie, who had a personality and couldn’t find any way to express it, her family being what it was: they thought that if you had a personality it was quite natural, you went ahead and expressed it as a matter of course and what was there to get excited about?

This was not enough for great-aunt Sallie. So she changed her religion. She quit being a Cumberland Presbyterian (the Faith of her Kentucky pioneer fathers) and she became a Seventh Day Adventist, her husband’s family being Methodist. And there-after she was a scourge to her entire community. As one of her relatives put it, “changing her religion put claws on Aunt Sallie.” I wish I knew her secret. It wasn’t change, I feel pretty certain, it was getting her bearings. I don’t want to be a scourge to anybody, I merely would like to stop being a scourge to myself. My whole impression of her, after hearing her history here and there through the years, is that she had the devil of a good time and died happy. What more can one ask?

Well, I am in the middle of her history now, and I wish I could just keep going in a trance until I had finished. Its too much to ask, I suppose. I can only write anything once, and if it isn’t finished then, its not apt to be…I made one draft of “Legend and Memory,” Gene in his charity wrote it out for me in a fair copy, and I made a few corrections. I simply have to do things that way or not at all…that means I have to sweep a track and make a dead run when I once start. And that is a very difficult thing to manage for. But never mind, Caroline, I’ll really do all I have planned, even yet.

You can’t think how it pleases me that you like the part of my manuscript you have read…The people of the Virginia Quarterly liked it, and so did Red: and I like being approved by a jury of my peers. If the southerners approve of each other know instantly what I am talking about…You do know that in this book, I am not looking up any facts, nor consulting with any one, nor going back to check my sources—nothing, I depend precisely on what I know in my blood, and in my memory, and on something that is deeper than knowledge. Your book was wonderful for another reason; you were back on your own territory, and you were writing of something you know, and you could go down the road a ways and ask a technical question if you needed to, and there is a most marvellous kind of here and nowness in your story. I cannot do that, I must depend on just what is in me, there is no one I can go to, I wish there were—

For example, I have curried a horse, and saddled him, and have ridden him, how many hundreds of times: and to this day I cannot really name the parts of a horse in a way that a horseman would approve, nor can I recall the names of all the pieces of harness I put on my horse, I really can ride but I do not know the names of the different ways of riding, this seat and that; I spent all my summers on a farm, and I do not know just when one plants cotton, or watermelons.

Now I don’t feel in the least wistful about it, dear Caroline, though it does sound a little that way. No, not at all. What really makes me sad and angry is that I seem never to learn to use the typewriter. This is a lovely little silent portable that Gene gave me for Christmas, and it is quite perfect in every way, with a wonderful three-language keyboard—accents for all the usual languages, and I can’t even hit the most familiar letters…

Katherine Anne

From Letters of Katherine Anne Porter. Edited by Isabel Bayley. New York: The Atlantic Monthly Press, 1990. pp. 125-8.

FURTHER READING

Read “The Grave,” published by The Virginia Quarterly Review in April 1935.

Read an essay published in The New Yorker on Porter: “I had nothing in the world but a kind of passion.”

Listen to The Martyr, a play written by Porter.