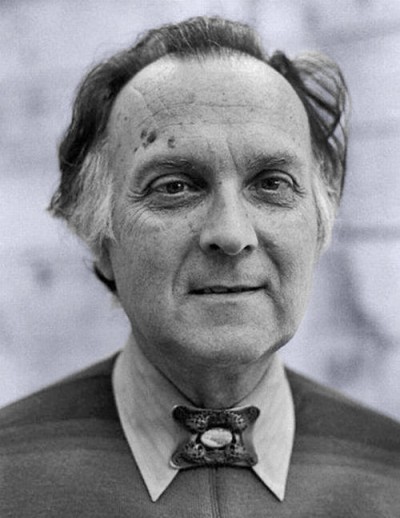

In 1958, poet and artist Robert Duncan moved into a Stinson Beach home with his partner, the mononymous visual artist Jess, and began to craft windows of glass and semiprecious stones commissioned by friends such as poet James Broughton. Duncan often wrote to his close correspondent, poet Denise Levertov, about their shared craft and sources of inspiration. Below, in a confessional letter, Duncan shares a dream with Levertov in which he is visited with a bout of “spiritual sickness.”

July 9, 1958

{Stinson Beach}

dear Denny,

With a fire on the hearth, and a foggy day, and poor Kit with a humiliating patch where we just clippd his back bare in our war on his eczema; coffee done and cups washd; but Jess is swearing at the mess of the table in the studio where I left the workings in progress of scattered moonstones, tweezers, broken and cut colord glass—the debris out of which we’ve been making plastic panels. I’ve finishd eight of twelve small panes for our bedroom window that faces on the road; and I’m working on a large bedroom window commissioned by Broughton that will be the first money I’ve earned in a long time. It’s been four months with few (only three) poems. In the last month these panels of plastic in which mosaics of translucent materials are suspended have provided a medium for my designing spirit to come to life in. Some imitation the soul can have of the ready burgeoning of geraniums and poppies. That we see all around us and even attend. Lettuce has a green translucence that rivals the rose. But how angry Jess’s broom sweeps up! and, well, my punishment is that once the clean-up started [I’d just sat down to this letter] I’m not permitted the somewhat expiation of participating. In a dream last week I’d decided I was spiritually sick and tho we had no money to afford it had to have a doctor’s care. After a series of encounters with stages previous to my case’s being accepted, elaborations of the waiting room (reception)—all of which enacted the idea of indulgence and excess and even exclusiveness involved (making it clear that the retreat I sought was socially fashionable; one was declaring oneself too sensitive and profoundly unusual to survive without care) I found myself “sick,” in a hospital bed. I had just witnessd four doctors and four nurses operating on James Broughton, probing beneath the epidermis, lifting up the skin to make pockets where the flesh was reachd—which was called “talking with the Id.” Jess sat by the (my) bedside and held my hand—my being “sick” and seeking help had been kept secret, until now; and worried too because the costs of my sickness were more than we could manage. Weeping (treacherously) I said when he askd what was the matter—“I’m so selfish it hurts” and felt, as if there were reason or vindication there, intimate pangs of a heart that had drawn up tight as a fist.

No wonder the few gifts—that in a colord window or a poem—my spirit can allow bring with their practice a sense of liberation. And Olson/Rimbaud’s becomes a text rememberd. “I’m not angry” dear Jess, “but I am, I’m angry at myself” Oh, the damnd litterd desk has been a kind of “I’m so selfish it hurts” statement,

Now we’ve, the two of us, made the bed, changed sheets and pillow cases and picked up shoes and clothes. My desk remains, a permitted debris of unanswered letters, unwritten Dahlberg review, of a crisis that needs only clearing away. News that’s no news of being eaten away by privilege.

****I’m not all a brood of mea culpa this morn. Tho Browning with his “the snail’s on the thorn” was no rose gardener, the snail’s himself so elegant a critter, in a sculptor’s dimension as extravagant a beauty as bee or butterfly. And there may be an economy yet that can share with the snail. That here verge upon pestilence, leaving lace of lettuce…

[…]

From The Letters of Robert Duncan and Denise Levertov. Edited by Robert J. Bertholf and Albert Gelpi. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 2004. Print.

FURTHER READING

Explore the collaborations between Robert Duncan and Jess.

Flip through Duncan and Jess’s shared scrapbook online.

Read the famous passage of Robert Browning’s Pippa Passes referenced above by Duncan.