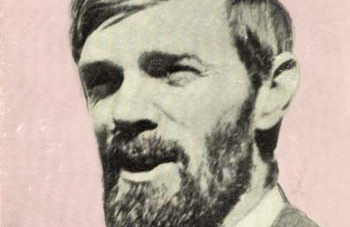

Due to his poor health, D. H. Lawrence was declared unfit for service in World War I. Here, Lawrence writes to his friend and future biographer Catherine Carswell, condemning the practice of military conscription and questioning the Christian doctrine of loving one’s neighbor as oneself.

Higher Tregerthen, Zennor,

St. Ives, Cornwall.

9th July, 1916.

My dear Catherine,—

I never wrote to tell you that they gave me a complete exemption from all military service, thanks be to God. That was a week ago last Thursday. I had to join the Colours in Penzance, be conveyed to Bodmin (60 miles), spend a night in barracks with all the other men, and then be examined. It was experience enough for me, of soldiering. I am sure I should die in a week, if they kept me. It is the annulling of all one stands for, this militarism, the nipping of the very germ of one’s being. I was very much upset. The sense of spiritual disaster everywhere was quite terrifying. One was not sure whether one survived or not. Things are very bad.

Yet I liked the men. They all seemed so decent. And yet they all seemed as if they had chosen wrong. It was the underlying sense of disaster that overwhelmed me. They are all so brave, to suffer, but none of them brave enough, to reject suffering. They are all so noble, to accept sorrow and hurt, but they can none of them demand happiness. Their manliness all lies in accepting calmly this death, this loss of their integrity. They must stand by their fellow man: that is the motto.

This is what Christ’s weeping over Jerusalem has brought us to, a whole Jerusalem offering itself to the Cross. To me, this is infinitely more terrifying than Pharisees and Publicans and Sinners, taking their way to death. This is what the love of our neighbour has brought us to, that, because one man dies, we all die.

This is the most terrible madness. And the worst of it all is that it is a madness of righteousness. These Cornish are most, most unwarlike, soft, peaceable, ancient. No men could suffer more than they, at being conscripted—at any rate, those that were with me. Yet they accepted it all: they accepted it, as one of them said to me, with one wonderful purity of spirit—I could howl my eyes out over him—because “they believed first of all in their duty to their fellow man.” There is no falsity about it: they believe in their duty to their fellow man. And what duty is this, which makes us forfeit everything, because Germany invaded Belgium? Is there nothing beyond my fellow man? If not, then there is nothing beyond myself, beyond my own throat, which may be cut, and my own purse, which may be slit: because I am the fellow-man of all the world, my neighbour is but myself in a mirror. So we toil in a circle of pure egoism…

If they had compelled me to go in, I should have died, I am sure. One is too raw, one fights too hard already, for the real integrity of one’s being. That last straw of compulsion would have been too much, I think.

Christianity is based on the love of self, the love of property, one degree removed. Why should I care for my neighbour’s property, or my neighbour’s life, if I do not care for my own? If the truth of my spirit is all that matters to me, in the last issue, then on behalf of my neighbour, all I care for is the truth of his spirit. And if his truth is his love of property, I refuse to stand by him, whether he be a poor man robbed of his wife and children, or a rich man robbed of his merchandise. I have nothing to do with him, in that wise, and I don’t care whether he keep or lose his throat, on behalf of his property. Property, and power—which is the same—is not the criterion. The criterion is the truth of my own intrinsic desire, clear of ulterior contamination.

I hope you aren’t bored. Something makes me state my position, when I write to you…

I have finished my novel, and am going to try to type it. It will be a labour—but we have got no money. But I am asking Pinker for some. And if it bores me to type the novel, I shan’t do it. There is a last chapter to write, some time, when one’s heart is not so contracted…

Greiffenhagen seems to be slipping back and back. I suppose it has to be. Let the dead bury their dead. Let the past smoulder out. One shouldn’t look back, like Lot’s wife: though why salt, I could never understand.

Have you got a copy of Twilight in Italy? If not, I have got one to give you. So just send me word, a p.c.

Frieda sends many greetings.

Yours,

D. H. Lawrence

I am amused to hear of Carswell’s divorce case.

FURTHER READING

Find a discussion of Catherine Carswell’s correspondence with D.H. Lawrence and others here.

Listen to a lecture by Catherine Brown on Lawrence and Christianity here.

For more of Lawrence’s impressions of military service in World War I, click here.