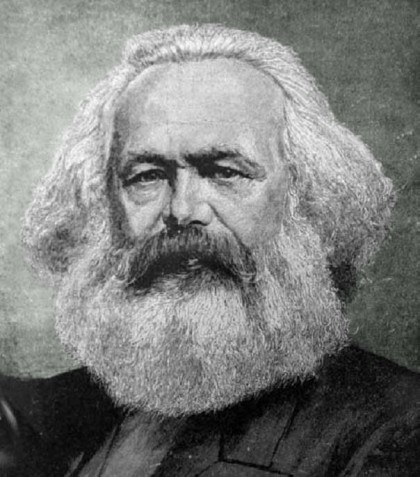

The letter below is a snapshot of the friendship between Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. At the time of writing, Marx had just published his first article with The New York Daily Tribune, to which he would be a frequent contributor until a shift on the paper’s editorial board in 1861. His main connection to the Tribune was through Charles Dana (referred to below), whose resignation was requested in 1862 due to the dramatic differences between his political views and those of founder Horace Greeley. Marx expresses his frustration with his financial situation as well as concern for the health of his wife and daughters.

London

8 September 1852

Dear Engels!

Your letter today dropped into a very disturbed atmosphere.

My wife is ill, little Jenny is ill, little Lene has a kind of nervous fever. I could not and cannot call the doctor because I have no money for medicine. For 8-10 days I have kept the family going on bread and potatoes, and it is even doubtful whether I can get these today. That diet of course was not conducive to health in the present climatic conditions. I’ve written no articles for Dana because I did not have a penny to go to read newspapers. Incidentally, as soon as you’ve sent No. XIX I’ll send you a letter with my opinion on XX, a summary of this present shit.

When I was with you and you told me you’d be able to obtain for me a somewhat larger sum by the end of August I wrote and told my wife to put her mind at rest. Your letters 3-4 weeks ago indicated that there was not much hope but nevertheless some. Thus I put off all creditors until the beginning of September, who, as you know, are always only paid small fragments. Now the storm is universal.

I have tried everything but in vain. First that dog Weydemeyer cheats me of 15£. I write to Germany to Streit (because he had written to Dronke in Switzerland). The pig doesn’t even reply. I turn to Brockhaus and offer him articles for Gegenwart, of harmless content. He declined in a very polite letter. Finally throughout last week I’ve been running around with an Englishman all day long because he wanted to obtain from me the discount for the bills on Dana. In vain.

The best and most desirable thing that could happen would be for my landlady to throw me out of the house. At least I would save the sum of 22£ then. But I can hardly expect her to be so obliging. Then there are the baker, the milkman, the tea fellow, the greengrocer, and an old butcher’s bill. How am I to cope with all this diabolical mess. In the end, during the past 8-10 days I borrowed a few shillings and pence from Knoten, which was the last thing I wanted to do but it was necessary in order not to croak.

You will have observed from my letters that, as usual when I am in it myself and do not just hear about it from afar, I am wading through the shit with great indifference. But what’s to be done? My house is a hospital, and the crisis is getting so disruptive that it compels me to give it my all-highest attention. What’s to be done?

Yours, K.M.

FURTHER READING

Peruse the archive of Marx’s contributions to the New York Daily Tribune.