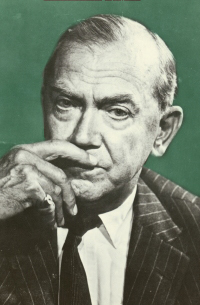

Graham Greene

Graham Greene

In the spring of 1946, Elizabeth Bowen and V. S. Pritchett convinced Graham Greene to join them in a formal, epistolary discussion on the role of the writer in society. The exchange was not completed until November of 1948, at which point a condensed form of it was published in the Partisan Review. Below, Greene’s response to Bowen, which argues for “two duties the novelist owes [to society]—to tell the truth as he sees it and to accept no special privileges from the state.”

+

TO ELIZABETH BOWEN

November, 1948, London

When your letter came, I had just been reading Mrs. Gaskell’s Life of Charlotte Brontë, and this sentence from one of Charlotte Brontë’s letters recurred to my mind. It certainly represents my view, and I think it represents yours as well: “You will see that Villette touches on no matter of public interest. I cannot write books handling the topic of the day; it is of no use trying it. Nor can I write a book for its moral. Nor can I take up a philanthropic scheme, though I honour philanthropy…”

Prichett, too, I think, would agree with that, though perhaps it was easier for Charlotte Brontë to believe that she had excluded public interest than it is for us. Public interest in her day was surely more separate from the private life: a debate in Parliament, a leading article in the Thunderer. It did not so colour the common life: with us, however consciously unconcerned we are, it obtrudes through the cracks of our stories, terribly persistent like grass through cement. Processions can’t help passing across the ends of our imaginary streets; our characters must earn a living: if they don’t what is called social significance seems to attach itself to their not-earning. Correcting proofs the other day, I had to read some old stories of mine dating back to the early thirties. Already they seemed to have a period air. It was not what I had intended.

‘The relation of the artist to society’: it’s a terribly vague subject, and I feel the same embarrassment and resentment as you do when I encounter it. We all have to be citizens in our spare time, standing in queues, filling up income tax forms, supporting our families: why can’t we leave it at that? I think we need a devil’s advocate in this discussion to explain the whole thing to us. I picture him as a member of the PEN Club, perhaps a little out of breath from his conference in Stockholm where he has been discussing this very subject (in pre-war times he would have returned from the Adriatic—conferences of this kind were never held where society was exactly thick.) Before sitting down to add his signature to an appeal in The Times (in the thirties it would have proudly appeared with Mr. Forster’s, Mr. Bertrand Russell’s and perhaps Miss Maude Royden’s), he would find an opportunity to tell us what society is and what the artist.

I’m rather glad, all the same, we haven’t got him with us. His letters confirmed the prejudice I felt against the artist (there the word is again) indulging in public affairs. His letters—and those of his co-signatories—always seemed to me either ill-informed, naïve or untimely. There were so many petitions in favour of the victims of arbitrary power which helped to knot the noose round the poor creatures’ necks. SO long as he had eased his conscience publicly in print, and in good company, he was not concerned with the consequences of his letter. No, I’m glad we’ve left him out. He will, of course, review us…

We had better, however, agree on our terms, and as you have suggested no alternative to Pritchett’s definition of society–‘people bound together for an end, who are making a future’—let us accept that. Though I’m not quite happy about it. We are each, however anachronistically and individually, making a future, or else the future, as I prefer to think, is making us—the death we are each going to die controlling our activities now, like a sheepdog, so that we may with least trouble be got through the gate. As for ‘people bound together for an end,’ the phrase does, of course, accurately describe those unfortunate prisoners of the French revolution of whom Swinburne wrote in Les Noyades: they were flung, you remember, naked in pairs into the Loire, but I don’t think Pritchett had that incident consciously in mind.

The artist is even more difficult to define: in most cases only time defines him, and I think for the purposes of this argument we should write only of the novelist, perhaps only of the novelist like ourselves, for obviously Wells will be out of place in any argument based on, say, Virginia Woolf. The word artists is too inclusive: it is impossible to make generalizations which will be true for Van Gogh, Burke, Henry James, Yeats and Beethoven. If a man sets up to be a teacher, he ahs duties and responsibilities to those he teaches, whether he is a novelist, a political writer or a philosopher, and I would like to exclude the teacher from the discussion. In the long run we are forced back to the egotistical ‘I’: we can’t shelter behind the great dead. What in my opinion can society demand of me? What I have got to render to Caesar?

First I would say there are certain human duties I owe in common with the greengrocer or the clerk—that of supporting my family if I have a family, of not robbing the poor, the blind, the window or the orphan, of dying if the authorities demand it (it is the only way to remain independent: the conscientious objector is forced to become a teacher in order to justify himself). These are our primitive duties as human beings. In spite of the fashionable example of Gauguin, I would say that if we do less than these, we are so much the less human beings and therefore so much the less likely to be artists. But are there any special duties I owe to my fellow victims bound for the Loire? I would like to imagine there are none, but I fear there are at least two duties the novelist owes—to tell the truth as he sees it and to accept no special privileges from the state.

I don’t mean anything flamboyant by the phrase ‘telling the truth’: I don’t mean exposing anything. By truth I mean accuracy—it is largely a matter of style. It is my duty to society not to write: ‘I stood above a bottomless gulf’ or ‘going downstairs, I got into a taxi,’ because these statements are untrue. My characters must not go white in the face or tremble like leaves, not because these phrases are clichés but because they are untrue. This is not only a matter of the artistic conscience but of the social conscience too. We already see the effect of the popular novel on popular thought. Every time a phrase like one of these passes into the mind uncriticised, it muddies the stream of thought.

The other duty, to accept no privileges, is equally important. The kindness of the State, the State’s interest in art, is far more dangerous than its indifference. We have seen how in time of war there is always some well-meaning patron who will suggest that artists should be in a reserved class. But how, at the end of six years of popular agony, would the artist be regarded if he had been reserved, kept safe and fattened at the public expense, too good to die like other men? And what would have been expected of him in return? In Russia the artist has belonged to a privileged class: he has been given a better flat, more money, more food, even a certain freedom of movement: but the State has asked in return that he should cease to be an artist. The danger does not exist only in totalitarian countries. The bourgeois state, too, has its gifts to offer the artist—or those it regards as artists, but in these cases the artist has paid like the politician in advance. One thinks of the literary knights, and then one turns to the plain tombstones with their bare hic jacets of Mr. Hardy, Mr. James, Mr. Yeats. Yes, the more I think of it, that is a duty the artist unmistakably owes to society—to accept no favours. Perhaps a pension if his family are in danger of starvation (in those circumstances the moralists admit that we may commit theft).

Perhaps the greatest pressure on the writer comes from the society within society: his political or religious group, even it may be his university or his employers. It does seem to me that one privilege he can claim, in common perhaps with his fellow human beings, but possibly with greater safety, is that of disloyalty. I met a farmer at lunch the other day who was employing two lunatics; what fine workers they were, he said; and how loyal. But of course they were loyal; they were like the conditioned beings of the brave new world. Disloyalty is our privilege. But it is a privilege you will never get society to recognize. All the more necessary that we who can be disloyal with impunity should keep that ideal alive.

If I may be personal, I belong to a group, the Catholic Church, which would present me with grave problems as a writer if I were not saved by my disloyalty. If my conscience were as acute as M. Mauriac’s showed itself to be in his essay ‘God and Mammon’, I could not write a line. There are leaders of the Church who regard literature as a means to one end, edification. That end may be of the highest value, of far higher value than literature, but it belongs to a different world. Literature has nothing to do with edification. I am not arguing that literature is amoral, but that it presents a personal moral, and the personal morality of an individual is seldom identical with the morality of the group to which he belongs. You remember the black and white squares of Bishop Blougram’s chess board. As a novelist, I must be allowed to write from the point of view of the black square as well as of the white: doubt and even denial must be given their chance of self-expression, or who is one freer than the Leningrad group?

Catholic novelists (I would rather say novelists who are Catholics) should take Newman as their patron. No one understood their problem better or defended them more skillfully from the attacks of piety (that morbid growth of religion). Let me copy out the passage. It really has more than one bearing on our discussion. He is defending the teaching of literature in a Catholic university:

‘I say, from the nature of the case, if Literature is to be made a study of human nature, you cannot have a Christian Literature. It is a contradiction in terms to attempt a sinless Literature of a sinful man. You may gather together something very great and high, something higher than any Literature ever was; and when you have done so, you will find that it is not Literature at all.’

And to those who, accepting that view, argued that we could do without Literature, Newman went on:

‘Proscribe (I do not merely say particular authors, particular works, particular passages) but Secular Literature as such; cut out from class books all broad manifestations of the natural man; and those manifestations are waiting for your pupil’s benefit at the very doors of your lecture room in living and breathing substances…Today a pupil, tomorrow a member of the great world: today confined to the Lives of the Saints, tomorrow thrown upon Babel…You have refused him the masters of human thought, who would in some sense have educated him because of their incidental corruption…’

Graham Greene

+