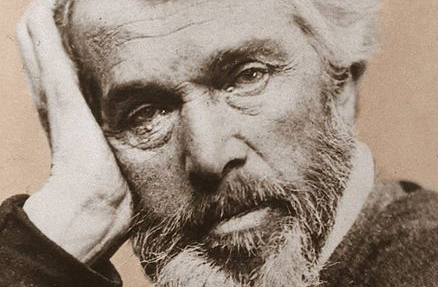

Here, an older Thomas Carlyle writes to his mother, commenting on the ongoing Irish Potato Famine, before considering how his wealth has contributed to a lull in his literary production.

My dear good Mother,

I purposed often, last week, to write you a little word; but was always put off again, by that old enemy, “one thing and another!” Not to be foiled a second time in the same way, I begin the week this time by doing that duty. A small duty, and a most blessed one, which ought not to be neglected!

We received Jenny’s Letter, and another of more detail from Jean; by which we had comfortable news of you in the cold weather, that you were among the Bairns, nestling down as quietly as you could, and on the whole doing pretty well in spite of the bitter winds and frosts. Our weather, here too, has been very cold all this while, and the Northeast with its smoke (for it brings all London on the top of us in comparison) still prevails: but we heap on flannel (as I hope you do), and coals, and struggle on with nothing hitherto but the discomfort for the time, and on the whole have nothing to complain of. The weather, I suppose, is very good for the plougher and sower: nobody ought to complain that has food and shelter at present! We hear that the Irish, in addition to all their other woes, are this year in many cases refusing to plough or sow the ground at all: they say, “Why should we raise a crop? Our Landlords will come and take it all; we shall get fed by the Government any way! We get a little money too for our horse-labour by carting Government-meal, at a penny a hundredweight for 10 miles; that is better than ploughing!” On the whole, I think there never was seen such a scene as that of Ireland; and I believe we are very far yet from having got to the bottom of it; the bottom of it does not yet seem to be visible to the generality. From one to two millions of men, some calculate, will perish;— and our time too, it seems very likely, lies close in the rear: I hope we may meet it a little more wisely!—

Jack and I have sent you various Newspapers for a little reading in the vacant afternoons. One always goes off too which is intended for James Aitken; Jack had one left with him to despatch thither last night: I do not know that it is a good Newspaper; it seemed far too small of print for one thing: but it is very cheap; and there is no good Weekly Newspaper here that I know of, except the Examiner, which would not at all suit James’s purpose I am afraid. They can write me about it by and by.

In the way of putting pen to paper I am still altogether inactive, and decline every offer made me by such poor hawkers as call on me by chance for that object: but in the way of sorting the abstruse confusions within my own self (which I suppose is the first condition of writing to any purpose) I have plenty to do! And for doing it, I find, one good condition is to hold your tongue if you can. Happily I now can: my poor Books bring me in a little money now, to fill the meal-barrel, every year; and the wealth of all the Bank of England is daily a smaller and smaller object to me,—indeed it is long since well near no object at all; which is perhaps a very good definition of being extremely rich; the “richest author in Britain” at present? I think I shall hold my tongue for a pretty while yet; and then, if I live, there will another word perhaps be found in me, which I shall be obliged to speak;—a terribly hard job when it comes. I read Books, but seldom find any that contain what I want: indeed one’s busiest time is often when altogether silent and quiescent, if one can stand to that rightly.— Jean says, “I must tell you whether I have no notion to be in Annandale soon; you will go home, and make ready for me, if I say yes.” Dear Mother, I know you will! But tho’ it is not at all impossible I may make some sally out of London if the season were warmed a little, and Annandale too may lie in the cards,—I have no thought that way at present; so stay still, and keep yourself warm and quiet where you are, so long as it is pleasant to you, dear Mother.—

Jack is very strong and brisk here; dining out considerably, rushing about among his old friends. We had him yesterday; indeed oftenest see him every day. I do not find that he has any specific project of work in his mind: the far feasiblest-looking thing I have heard him hint, is that of setting up house in Dumfries with you and Jenny, “and practising gratis among the poor”; but, for that, he has come away at the wrong season; and indeed I think the matter is still very far from being matured in his mind.— Dear Mother, here is a man coming (I hear his knock!) to take me out; here he enters! a gratis ride; it will do me good. But so I must end abruptly: in a very short time I will write again. Adieu dear Mother: commend both of us to Jenny and Jean and all the rest.

Ever Affectionately,

Your son,

Tom