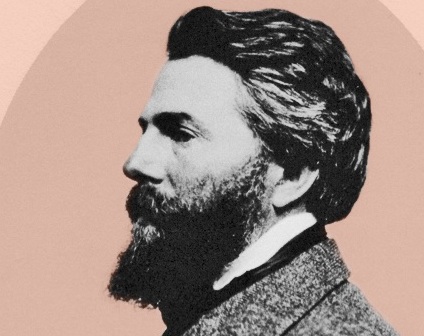

In the following letter Herman Melville addresses Sophia Hawthorne, wife of Nathaniel, responding to her comments on the recently published Moby Dick. Melville makes brief mention of Sophia Hawthorne’s words, his real point of interest being her husband’s allegorical interpretation of the novel. The intimate correspondence between the two writers had recently cooled; both continued to advocate for the other’s work, but they would meet only twice more in life. Scholars attribute the break to Melville’s overzealous idolatry of the wary Hawthorne.

To Sophia Hawthorne

8 January 1852

[Embossed trademark, “Bath”]

New York Jan: 8th 1852

My Dear Mrs. Hawthorne

I have hunted up the finest Bath I could find, gilt-edged and stamped, whereon to inscribe my humble acknowledgment of your highly flattering letter of the 29th Dec:—It really amazed me that you should find any satisfaction in that book. It is true that some men have said they were pleased with it, but you are the only woman—for as a general thing, women have small taste for the sea. But, then, since you with your spiritualizing nature, see more things than other people, and by the same process, refine all you see, so that they are not the same things that other people see, but things which while you think you but humbly discover them, you do in fact create them for yourself—Therefore, upon the whole, I do not so much marvel at your expression concerning Moby Dick. At any rate, your allusion for example to the “Spirit Spout” first showed to me that there was subtle significance in that thing—but I did not, in that case, mean it. I had some vague idea while writing it, that the whole book was susceptible of an allegoric construction, & also that parts of it were—but the specialty of many of the particular subordinate allegories, which, without citing any particular examples, yet intimated the part-parcel allegoricalness of the whole.—But, My Dear Lady, I shall not again send you a bowl of salt water. The next chalice I shall commend will be a rural bowl of milk.

And now, how are you in West Newton? Are all domestic affairs regulated? Is Miss Una content? And Master Julien satisfied with the landscape in general? And does Mr. Hawthorne continue his series of calls upon all his neighbors within a radius of ten miles? Shall I send him ten packs of visiting cards? And a box of kid gloves? And the latest style of Parisian handkerchief?—He goes into society too much altogether—seven evenings out, a week, should content any reasonable man.

Now, madam, had you not said anything about Moby Dick, & had Mr. Hawthorne been equally silent then had I said perhaps some to both of you about another Wonder Book. But as it is, I must be silent. How is it, that while all of us human beings are so entirely disembarrassed in censuring a person; that so soon as we would praise, then we begin to feel awkward? I never blush after denouncing a man: but I grow scarlet, after eulogizing him. And yet this is all wrong; and yet we can’t help it; and so we see how true was that musical sentence of the poet when he sang—

“We can’t help ourselves”

For tho’ we know what we ought to be; & what it would be very sweet & beautiful to be; yet we can’t be it. That is most sad, too. Life is a long Dardenelles, My Dear Madam, the shores whereof are bright with flowers, which we want to pluck, but the bank is too high; & so we float on & on, hoping to come to a landing-place at last—but swoop! we launch into the great sea! Yet the geographers say, even then we must not despair, because across the great sea, however desolate & vacant it may look, lies all Persia & the delicious lands roundabout Damascus.

So wishing you a pleasant voyage at last to the sweet & far countree—

Beleive [sic] Me

Earnestly Thine—

Herman Melville

I forgot to say, that your letter was sent to me from Pittsfield—which delayed it.

My sister Augusta begs me to send her sincerest regards both to you & Mr. Hawthorne.

Note: Melville makes a rift on Hawthorne’s social excursions; the notorious recluse rarely ventured outside of his home for matters other than business.

The “rural bowl of milk” would come to be Pierre: or, The Ambiguities.

From The Letters of Herman Melville. Edited by Merrell R. Davis and William H. Gilman. New Have: Yale University Press, 1960.

FURTHER READING

The tale within a tale: Greek myths in Hawthorne’s Wonder Book.

The meeting of the two literary giants, providence of a thunderstorm.

Melville’s beautiful copy of Mosses from an Old Manse, gift of Hawthorne, replete with pressed liverworts.