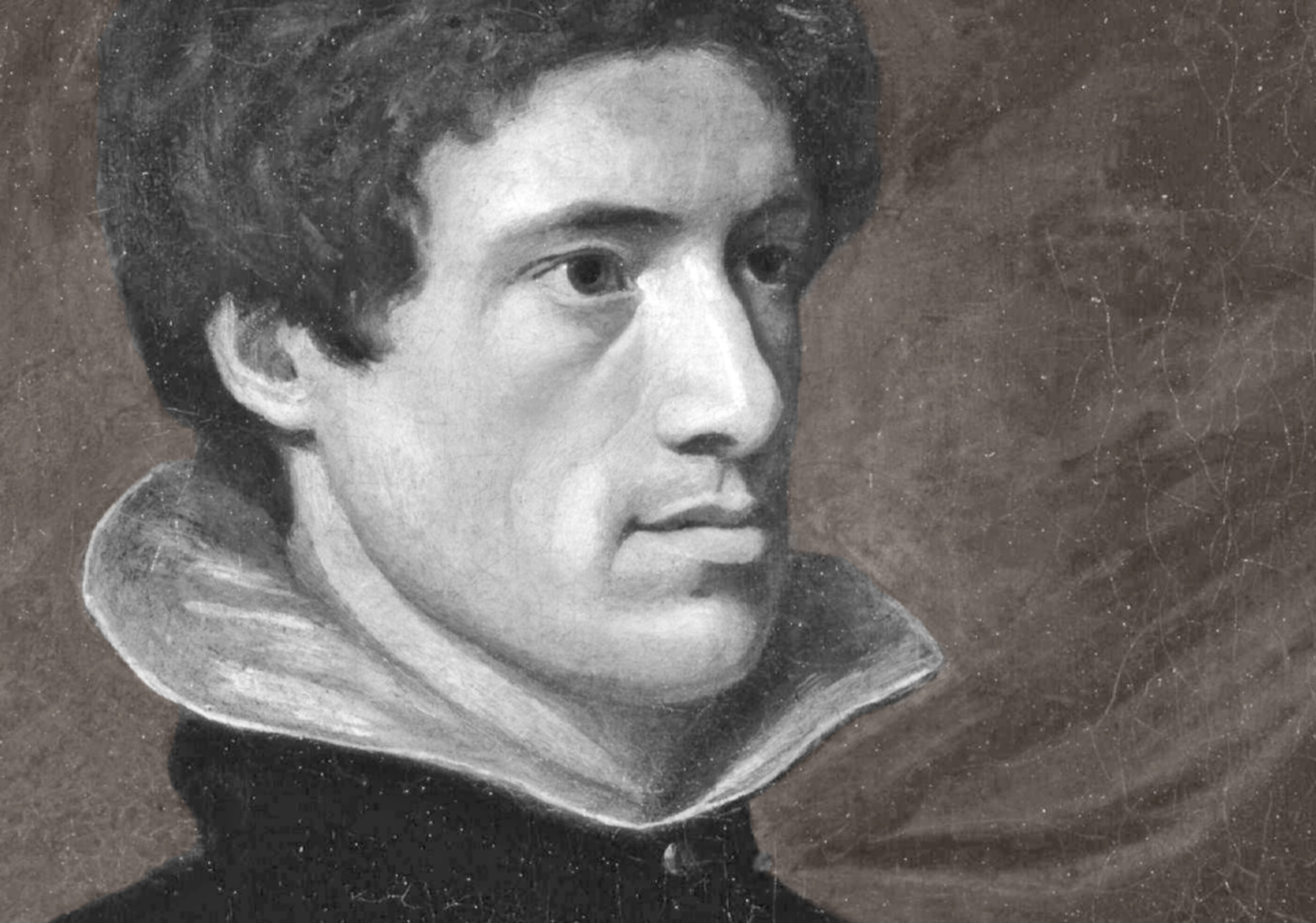

Below, the English writer and essayist Charles Lamb writes an affectionate thank you letter to friend H. Dodwell for the gift of a pig, before playfully complaining about the lack of “gentlemen” in civil service since Dodwell’s departure.

October 7, 1827

H. Dodwell, Esq.

Maidenhead, Berks.

Let us meet if possible when you hobble to town. Enfield Chase, nearly opposite to the 1st chapel; or better to define it, east side opposite a white House in which a Mrs. Vaughan (in ill health) still resides.

My dear Dodwell—Your little pig found his way to Enfield this morning without his feet, or rather his little feet came first, and as I guessed the rest of him soon followed. He is quite a beauty. It was a pity to kill him, or rather, as Rice would say, it would have been a pity not to kill him in his state of innocence. He might have lived to be corrupted by the ways of the world, and for all his delicate promise have turned out, like an old Tea Broker you and I remember, a lump of fat rusty Bacon. Bacon was a Beast, my friend at Calne, Marsh, used to say—or was it Bendry? A rather of the latter still hangs up in Leadenhall. Your kind letter has left a relish upon my taste; it read warm and short as to-morrow’s crackling.

I am not quite so comfortable at home yet as I should be else in the neatest compactest house I ever got—a perfect God-send; but for some weeks I must enjoy it alone. She always comes round again. It is a house of a few years’ standing, built (for its size with every convenience) by an old humourist for himself, which he tired of as soon as he got warm in it. Grates, locks, a pump, convenience indescribable, and cheap as if it had been old and craved repairs. For me, who always take the first thing that offers, how lucky that the best should first offer itself! My books, my prints are up, and I seem (so like this room I write in is to a room there) to have come here transported in the night, like Gulliver in his flying house; and to add to the deception, the New River has come down from Islington with me. ‘Twas what I wished—to move my house, and I have realised it. Only instead of company seven nights in the week, I see my friends on the First Day of it, and enjoy six real Sabbaths. The Museum is a loss, but I am not so far but I can visit it occasionally: and I have exhausted the Plays there.

“Indisputably I shall allow no sage and onion to be cramm’d into the throat of so tender a suckling.

“Bread and milk with some odoriferous mint, and the liveret minced.

“Come and tell me when he cries, that I may catch his little eyes.

“And do it nice and crisp.” (That’s the Cook’s word.) You’ll excuse me, I have been only speaking to Becky about the dinner to-morrow. After it, a glass of seldom-drunk wine to my friend Dodwell, and, if he will give a stranger leave, to Mrs. Dodwell: then to the memory of the last, and of the last but one, learned Dodwell, of whom, but not whom, I have read so much. The next to the “Outward and Homeward bound ships”—and, if the bottle lasts, to the Chairman, Deputy-Chairman, the Court of Directors, the Secretary, the Treasurer, and Accomptant-General, of the East India Company, with a blunt bumper at parting to P—. All I can do, I cannot make P—look like a G—n, yet he is portly, majestic, hath his nods, his condescensions, his variety of behaviour to suit your Director, your Upper Clerk, your Ryles, and your Winfields; he tempers mirth with gravity, gives no affront, and expects to receive none, is honourable, mannered, of good bearing, looks like a man who, accustomed to respect others, silently extorts respect from them, has it as a sort of in course; without claiming it, finds it. What do I miss in him, then, of the essentials of gentlemanhood? He is right sterling—but then, somehow, he always has that d—d large Goldsmith’s Hall mark staring upon him. Possibly he is too fat for a gentleman—then I think of Charles Fox in the Dropsy: and the burly old Duke of Norfolk, a nobleman, every stun of him!

I am afraid now you and — are gone, there’s scarce an officer in the Civil Service quite comes up to my notion of a gentleman. D— certainly does not, nor his friend B—.

C— bobs. K— curtsies. W— bows like the son of a citizen; F— like a village apothecary; C— like the Squire’s younger Brother; R— like a crocodile on his hind legs; H— never bows at all—at least to me. S— splutters and stutters. W— halters and smatters. R— is a coal-heaver. Wolf wants my clothing. C— simmers, but never boils over. D— is a Butterfirkin, salt butter. C—, a pepper-box, cayenne. For A—, E—, and O—, I can answer that they have not the slightest pretensions to anything but rusticity. Marry, the remaining vowels had something of civility about them. Can you make top or tail of this nonsense, or tell where it begins? I will page it. How an error in the outset infects to the end of life, or of a sheet of paper!

Cordially adieu.

C. Lamb

From The Complete Works and Letters of Charles Lamb. New York: The Modern Library, 1935. pp. 936-7.

FURTHER READING

Dive into a few of the many essays written by Charles Lamb.

Buy yourself a piece of history, view some of Charles Lamb’s estate that’s up for auction.

If you’re across the pond, take a walking tour, and enjoy some of Charles Lamb’s last steps.