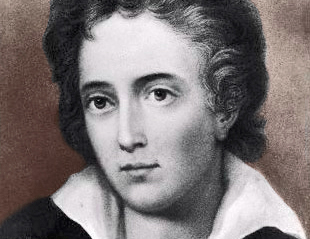

Percy Bysshe Shelley and Thomas Jefferson Hogg met during their studies at Oxford University; the two friends were expelled in 1811 after they published The Necessity of Atheism, a flowery restatement of David Hume’s skeptical philosophy. In the letter below, Shelley reminisces over their youthful fireside conversations while denouncing the fault of pride. John Keats once suggested that Shelley “curb his magnanimity,” referencing an irascible passion for reform. The need for such curbing becomes apparent in the letter below.

To Thomas Jefferson Hogg

Tanyrallt [Tremadoc]

Feb[ruary] 7, 1813

My Dear Friend,

I have been teased to death for the last fortnight. Had you known the variety of the discomfitures I have undergone, you would attribute my silence to anything but unkindness or neglect. I allude to the embankment affairs, in which I thoughtlessly engaged; for when I come home to Harriet, I am the happiest of the happy. I forget whether I have expressed to you the pleasure which you know I must feel at your visit in March. I hope it will be early in the month, and that you will arrange matters so in London, that it may be protracted to the utmost possible length.

We simple people live here in a cottage extensive and tasty enough for the villa of an Italian Prince. The rent, as you may conceive, is large, but it is an object with us that they allow it to remain unpaid until I am of age.

You must take your place in the mail as far as Capel Cerrig, and inform me of the time you mean to be there, and I will meet you. I do not think that you have ever visited this part of North Wales. The scenery is more strikingly grand in the way from Capel Cerrig to our house than I ever beheld. The road passes at the foot of Snowdon; all around you see lofty mountain peaks, lifting their summits far above the clouds, wildly-wooded valleys below, and dark tarns reflecting every tint and shape of the scenery above them. The roads are tremendously rough; I shall bring a horse for you, as you will then be better able to see the country than when jumbled in a chaise.

“Mab” has gone on but slowly, although she is nearly finished. They have teased me out of all poetry. With some restrictions, I have taken your advice, though I have not been able to bring myself to rhyme. The didactic is in blank heroic verse, and the descriptive in blank lyrical measure. If an authority is of any weight in support of this singularity, Milton’s “Samson Agonistes,” the Greek Choruses, and (you will laugh) Southey’s “Thalaba” may be adduced. I have seen your last letter to Harriet. She will answer it by next post. I need not say that your letters delight me, but all your principles do not. The species of pride which you love to encourage appears to me incapable of bearing the test of reason. Now, do not tell me that Reason is a cold and insensible arbiter. Reason is only an assemblage of our better feelings—passion considered under a peculiar mode of its operation. This chivalric pride, although of excellent use in an age of Vandalism and brutality, is unworthy of the nineteenth century. A more elevated spirit has begun to diffuse itself, which, without deducting from the warmth of love, or the constancy of friendship, reconciles all private feelings for public unity, and scarce suffers true Passion and true Reason to continue at war. Pride mistakes a desire of being esteemed for that of being really estimable. I scarce think that the mock humility of ecclesiastical hypocrisy is more degrading and blind. I remember when over our Oxford fire we used to discuss various subjects; fancy me present with you in spirit, and own “how vain is human pride!” Perhaps you will say that my Republicanism is proud; it certainly is far removed from pot-house democracy, and knows with what smile to hear the servile applauses of an inconsistent mob. But though its cheeks could feel without a blush the hand of insult strike, its soul would shrink neither from the scaffold nor the stake, nor from those deeds and habits which are obnoxious to slaves in power…

Since I wrote the above, I have finished the rough sketch of my poem…Like all egotists, I shall console myself with what I may call, if I please, the suffrages of the chosen few, who can think and feel, or of those friends whose personal partialities may blind them to all defects. I mean to subjoin copious philosophical notes.

Harriet has a bold scheme of writing you a Latin letter. If you have Ovid’s “Metamorphoses,” she will thank you to bring it. I do not teach her grammatically, but by the less laborious method of teaching her the English of Latin words, intending afterwards to give her a general idea of grammar. She unites with me in all kindest wishes.

Notes: Shelley writes from the coast of Wales, where he was sustaining an elopement with Harriet Westbrook. The two would be married shortly thereafter. Shelley left Westbrook after she mothered two of his children, Ianthe and Charles.

Hogg published the first two volumes of Shelley’s biography in 1858, a few decades after his friend’s death. Hogg’s writing was so self-involved, his tone so disparaging, that he would subsequently be estranged from the remainder of the Shelley family.

From The Letters of Percy Bysshe Shelley. Edited by Roger Ingpen. New York: Scribner, 1909. p. 380–383.

FURTHER READING

Shelley’s search for himself.

The UK’s Rationalist Association assesses the poet’s humanism.

The portal devoted to “Shelley’s Ghost, exhibited at the Schwarzman Building in NYC. See a sketch of a Hogg, playing chess.