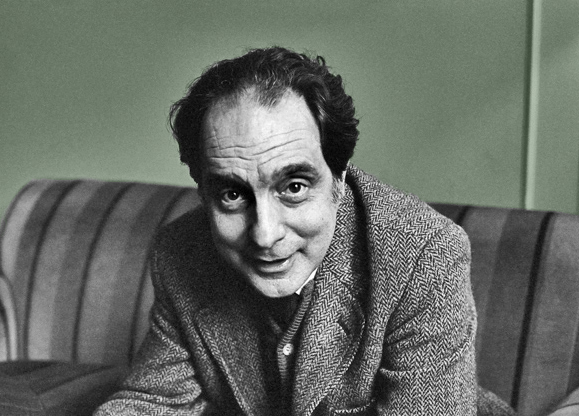

Italo Calvino addresses Carlo Salinari, a prominent Italian literary critic who had written a review of Calvino’s Il visconte dimezzato (The Cloven Viscount) in l’Unità, a Communist newspaper. The novella tells the tale of a nobleman who is split into two distinct parts after being struck by a cannonball. Each half of the original person carries a distinct personality of its own, one being purely good while the other is evil. Calvino wrote the novella after struggling with the manuscript he mentions below, I giovani del Po, which he stopped working on in 1951. It was never published.

Turin, 7 August 1952

Dear Salinari,

I’ve read your article on my book. I agree with the external definition, if we can call it that: a literary divertissement, a bravura piece, a nod to those in the know, something for a restricted circle of readers, and all the limitations that such a definition involves.

On the other hand, I cannot concur with your definition of the book’s central motif. The fact that man is a mixture of good and evil actually mattered very little to me; that is old hat and predictable, as everyone knows. What I was interested in was the problem of contemporary man (or rather intellectual, to be more precise) who is divided, that is to say incomplete, “alienated.” If I decided to split my protagonist down the line of the good-evil fracture, I did so because that allowed me a greater clarity of contrasting images, and it was connected with a literary tradition that was already something of a classic (for instance, Stevenson) so that I could play with it without worrying. Whereas my moralizing winks, so to speak, were aimed not so much at the viscount as at the frame characters, who are the real exemplifications of my argument. In other words, the lepers (i.e., decadent artists), the doctor, and the carpenter (science and technology detached from humanity), those Huguenots, seen with a bit of sympathy and with a bit of irony (they are in a sense an autobiographical allegory of mine portraying my family [a kind of imaginary, genealogical epic of my family], and also an image of the whole line of bourgeois idealist moralizing from the Reformation to Croce).

You will say: but none of this can be understood from the text. And on this score all I can do is say you’re right. The “anti-historicism” of the book, in my view, is not in its thematics, but is actually in its nature as a kind of game, which does not require allegories to be looked for, though at the same time suggesting them, whereas the books we most need are those that are explicit and devoid of allusions. That does not take away from the fact that one can still write books like this; it’s just that we also have to write the other books too, the real ones.

I had written another book that was completely different, one which had cost me a lot of effort; now it’s with Michele Rago, and I’ve written to him to let you read it too. Up until now it has not met with any good fortune and I think I’ll have to resign myself to leaving it unpublished, even though I was very keen on it. Instead, The Cloven Viscount, written to give my imagination a holiday after punishing it in the other novel, has enjoyed a success that I would never have expected for it. I thought of publishing it in a journal like Botteghe Obscure because publishing it in a book would have seemed to give it too much importance; but basically “I Gettoni” also have a public the size of a journal and I published it in that series. I know that the success it has enjoyed is out of all proportion and partly ambiguous, and I don’t trust it; in fact I can’t wait to make some people eat their own words of exaggerated praise. But I think the forbidding faces of some comrades are also exaggerated. This is a story in a genre where I could write another ten or twenty such tales, and without much effort, if I weren’t completely taken up with the desire to write things that I believe are more important. And my ideal would be to manage to write in equal measure, and ideally with equal facility, “useful” things and “amusing” things. And possibly things that are useful and amusing at the same time.

That’s my plan of work for the next ten years at least.

Calvino

FURTHER READING

A review of The Cloven Viscount and The Non-Existent Knight.

One of the first reports on Calvino’s early popularity in the US.

Gore Vidal writes about Calvino’s life and death.