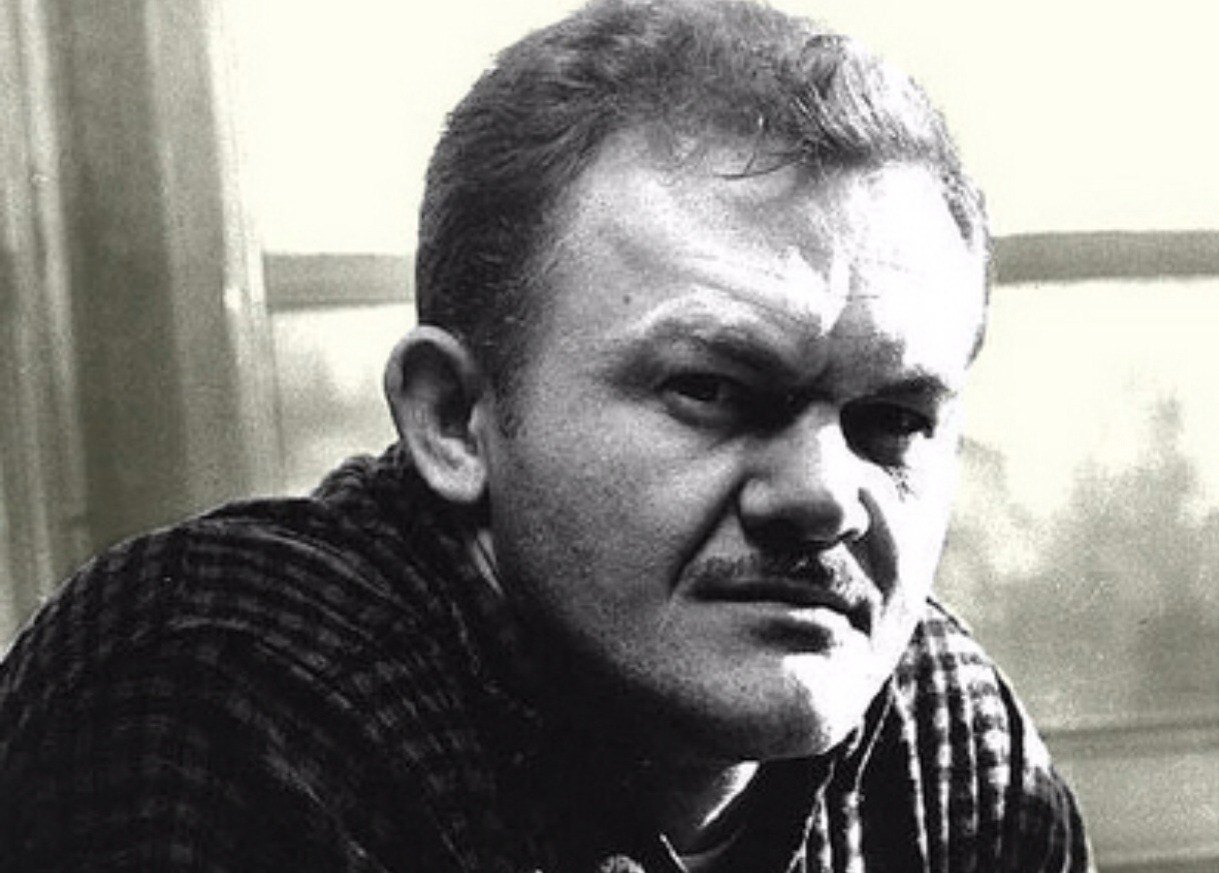

In the following letter James Jones, best known for his reflections on WWII and its aftermath, addresses his brother. Though never referencing the event directly, Jones was undoubtedly writing in the emotional wake of his mother’s death, which had occurred a month before. This letter was his first attempt at taking pen to paper after learning of the news, and he was determined not to talk about the family’s loss, asking his brother to remain quiet on the subject as well. While struggling with the onset of depression, Jones took consolation in the artistic achievement of Thomas Wolfe: “His home life seemed so similar to my own, his feelings about himself so similar to mine about myself, that I realized I had been a writer all my life without knowing it or having written.” As he expands upon below, this feeling of empathy encouraged Jones in his literary aspirations, aspirations which he would achieve with the publication of From Here to Eternity (winner of the National Book Award in 1952).

Hawaii

Monday, April 7, 1941

Dear Jeff,

I wrote to Dad about a week ago. Apparently, he wrote to you before he received my letter. I tried to explain the way I felt—without much success, I’m afraid—and tried to help him, what little I was able. It’s hard as hell to try to write a letter of that sort, especially when you’ve been away so long without any contact except writing. I felt so futile and helpless about it…If it’s all the same to you, I’d rather just drop the subject and not refer to it in future letters.

I’m sorry I haven’t written you for so long. Now that I’m a clerk in the orderly room, I’ve been spending all my spare time in there, writing. I have full access to the place, and it’s a good place to write: no one can come in and bother me, and I can stay there all night, if I choose.

I’m really serious about this writing thing. What time I haven’t been writing, I’ve been reading: Thomas Wolfe, if you know who he is. His writing is mostly built about the central character of a writer, himself. Although it’s fiction, it deals with his life and experiences. In my opinion, little as it’s worth, he is the greatest writer that has lived, Shakespeare included. He is a genius. That is the only way to describe him. And in reading of his childhood, his youth, and his struggles to get out of him the things he wanted to say, I can find an almost exact parallel with myself. Of course details are different, but the general trend is practically the same…

I, too, like Wolfe, have felt myself different from other kids, especially while I was in high school: I never seemed to mix with the other kids; I didn’t think at all like they did; I never ran around with the gang of boys that were the elite of the campus, nor did I run around with the gang that envied them and disliked them, and ganged together in a sort of mutual protection, because they were excluded from the select group: I did feel hurt about it, and I wasn’t able to understand it; but I don’t think I was little about it. I fell into the habit of going with myself, and expressing my “radical” thoughts to no one. Even at home they didn’t see things the way I did. Don’t think I’m a victim of an inferiority complex or an aesthete, who is always complaining he is misunderstood, because I’m not. I don’t feel sorry for myself. I’ve gotten so that I like my own company. I can understand me better than anyone I know.

Anyway, it seems I’ve always felt a hunger and unrest that nothing could satisfy. I couldn’t understand what it was. It was like an idea for a story you have in the back of your head that you can’t quite grasp. You know it’s there, but it keeps receding before your grasp like a mist. Do you remember when I fell so hard for that girl in Findlay? (If you don’t remember her name, then I won’t say it for the thing is forgotten and in the past now.) We had even talked about getting married. But something, some vague wisp of dissatisfaction kept sifting thru [sic] my mind. I didn’t know what it was then. I think I do now: It’s that desire to write, to be famous and adored, to be known and talked about by people I’ve never seen. Yet, that’s not all it is. It’s more than that. I—well, I don’t want to go melodramatic on you. I’m afraid you’ll laugh at me.

…You know there’s really nobody that I can talk to with[out] being afraid of being laughed at, not even you. Right now, I’m afraid you’ll laugh when you read this; or worse, feel sorry for me and pity me, because I’m a[n] idealistic, romantic kid, who doesn’t know what in the hell he’s talking about. In fact, this is the first time I’ve ever come anywhere near telling you what I thought.

Which brings me to another subject, one I hope you’ll say nothing about to anyone, not Sally, Dad, and least of all, the one involved, if you should ever run across her in rambling thru the metropolis…I’m very strongly afraid the old cynic has fallen again.

I doubt if you remember…. Probably you never met her. She was in my class in high school. Very smart: Editor of the N ’n E [Notes ‘n Everything, a school publication], 4 A student, et al. I had a few dates with her in high, but never succeeded in kissing her, a fact which made me mark her off my list quickly, altho I did have a lot of fun with her. Well, she asked Tink [Mary Ann Jones] two or three times to ask me to write her, after I got here. Tink mentioned it a couple of times and one day down at Hickam, when I had nothing to do, I wrote her a little letter and inclosed a copy of that poem about the soldier I sent to you (that was after I had gotten the corrected copy back from you). It was a pretty raw thing to do, especially in a first letter, what with its knocking women in general and all; but I was feeling low and wanted to shock hell out of somebody. Well, I got an answer pretty quickly. She liked it and wanted to know if that was the way I really felt. From that [inauspicious] beginning our correspondence as founded. I’ve sent her copies of my stories, poems, and of the sketches and descriptions I’ve been writing ever since I got out of the hospital. I’ve written her exactly as I feel, mincing no words, speaking the truth exactly as I felt it. I’ve written her my ambitions, hopes, fears, just everything. I guess.

As far as I’m able to discern, I am in love with her. I don’t think I really knew it until I got her last letter.

You see, she is engaged to marry some guy in Robinson. I’ve known about it since her first letter. In her next to last letter, she told me they planned on getting the bowline twisted in June; and proceeded to ask me whether or not we should continue writing—now. It seems her OAO [one and only] got very jealous, and that he suspected her of corresponding with me. She didn’t know whether she should write to me, when he felt that way. She was afraid of messing things up. She didn’t love me, but she did enjoy writing me, and hearing from me.

Well, the outcome was, that I wrote her a very strong letter. (I’ll send you a copy of it sometime, if you like, for that’s the only way I could describe the thing.) I told her that I’d never had anyone I’d been able to write to like I could her, and suggested he censor all letters, among other things. I also got pretty frank about the marriage business. The matter of fact way she talked about marrying him got under my skin: she talked just as if she were going on a picnic, or out to buy a new dress.

Well, she met me word for word, phrase for phrase. I guess it was when I got that letter that I realized I was in love with her. I wouldn’t let her know it for the world. In the first place, it would destroy the frankness that exists between us and in the second place, I know she loves this other guy (at least, I think I know), and I can’t stand to be pitied, laughed at, or felt sorry for by anyone.

…She thinks my stories are great, and that I have a great future as a writer. I’d like to think she’s right. But…I’m working in the dark all the time. Whenever I do write something, that black, forbidding doubt is in me, making me wonder if I’m just some damned egotistical fool, or if I really have that spark of genius it takes to be a really great author like Wolfe. If I only had some way of knowing. If only some authority that knew would tell [me] I was good and had promise, then I’d be all right, but as it is, I’m always full of that fear that maybe I’m not any good. Sometimes I get so damned low I feel like blowing my brains out…

Love to Sally and Dave,

Jim

From To Reach Eternity: The Letters of James Jones. New York: Random House (1989).

FURTHER READING

After a long run in its censored version, From Here to Eternity is now published in its original form, scandals and profanities included.

On Guadalcanal.

Jones’ interview at The Paris Review.