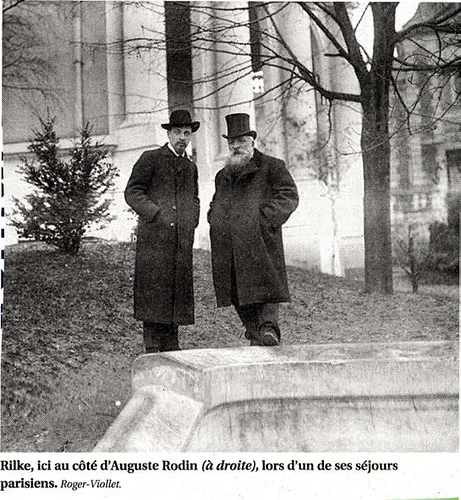

Rilke and Auguste Rodin

Rilke and Auguste Rodin

In the summer of 1902, Rainer Maria Rilke left his wife, Clara, and daughter, Ruth, and went to Paris, where he worked for a time as the private secretary of Auguste Rodin.

TO CLARA RILKE

September 5, 1902, Paris

[…] I believe much has now been revealed to me at Rodin’s recently. After a déjeuner that passed no less uneasily and strangely than the one I last mentioned, I went with Rodin into the garden, and we sat down on a bench which looked out wonderfully far over Paris. It was still and beautiful. The little girl (it is probably Rodin’s daughter), the little girl had come with us without Rodin’s having noticed her. Nor did the child seem to expect it. She sat down not far from us on the path and looked slowly and sadly for curious stones in the gravel. Sometimes she came over and looked at Rodin’s mouth when he spoke, or at mine, if I happened to be saying something. Once she also brought a violet. She laid bashfully with her little hand on that of Rodin and wanted to put it in his hand somehow, to fasten it somehow to that hand. But the hand was as though made of stone, Rodin only looked at it fleetingly, looked past it, past the shy little hand, past the violet, past the child, past this whole little moment of love, with a look that clung to the things that seemed continually to be taking shape in him.

He spoke of art, of art dealers, of his lonely position and said a great deal that was beautiful which I rather sensed than understood, because he often spoke very indistinctly and very rapidly. He kept coming back to beauty which is everywhere for him who rightly understands and wants it, to things, to the life of these things – de regarder une Pierre, le torse d’une femme. …And again and again to work. Since physical, really difficult manual labor has come to count as something inferior – he said, work has stopped altogether. I know five, six people in Paris who really work, perhaps a few more. There in the schools, what are they doing year after year – they are “composing.” In so doing they learn nothing at all of the nature of things. Le modelé (ask your Berlitz French woman sometime how one could translate that, perhaps it is in her dictionary). I know what it means: it is the character of the surfaces, more or less in contrast to the contour, that which fills out all the contours. It is the law and the relationship of these surfaces. Do you understand, for him there is only le modelé…in all things, in all bodies; he detaches it from them, makes it, after he has learned from them, into an independent thing, that is, into sculpture, into a plastic work of art. For this reason, a piece of arm and leg and body is form him a whole, an entity, because he no longer things of arm, leg, body (that would seem to him too like subject matter, do you see, too – novelistic, so to speak), but only of a modelé which completes itself, which is, in a certain sense, finished, rounded off.

The following was extraordinarily illuminating in this respect. The little girl brought the shell of a small snail she had found in the gravel. The flower he hadn’t noticed, – this he noticed immediately. He took it in his hand, smiled, admired it, examined it and said suddenly: Voilá le modelé grec. I understood at once. He said further: Vous savez, ce n’est pas la forme de l’object, mais: le modelé. …Then still another snail shell came to light, broken and crushed…: –C’est le modelé gothique-renaissance, said Rodin with his sweet, pure smile! …And what he meant was more or less: It is a question for me, that is for the sculptor par excellence, of seeing or studying not the colors or the contours but that which constitutes the plastic, the surfaces. The character of these, whether they are rough or smooth, shiny or dull (not in color but in character!). Things are infallible here. This little snail recalls the greatest works of Greek art: it has the same simplicity, the same smoothness, the same inner radiance, the same cheerful and festive sort of surface. …And herein things are infallible! They contain laws in their purest form. Even the breaks in such a shell will again be of the same kind, will again be modelé grec. This snail will always remain a whole, as regards its modelé, and the smallest piece of snail shell is still always modelé grec. …Now one notices for the first time what an advance his sculpture is. What must it have meant to him when he first felt that no one had ever yet looked for this basic element of plasticity! He had to find it: a thousand things offered it to him: above all the nude body. He had to transpose it, that is to make it into his expression, to become accustomed to saying everything through the modelé and not otherwise. Here, do you see, is the second point in this great artist’s life. The first was that he had discovered a new basic element of his art, the second, that he wanted nothing more of life than to express himself fully and all that is his through this element. He married, parce qu’il faut avoir une femme, as he said to me (in another connection, namely when I spoke of groups who join together, of friends, and said I thought that only from solitary striving does anything result anyway, then he said it, said: Non, c’est vrai, il n’est pas bein de faire des groupes, les amis s’empêchent. Il est mieux d’être seul. Peut-être avoir une femme – parcequ’il faut avoir une femme) … something like that.

– Then I spoke of you, of Ruth, of how sad it is that you must leave her, – he was silent for a while and said then, with wonderful seriousness he said it: … Oui, il faut travailler, rien que travailler. Et il faut avoir patience. One should not of wanting to make something, one should try only to build up one’s own medium of expression and to say everything. One should work and have patience. Not look to right nor left. Should draw all of life into this circle, have nothing outside of this life. Rodin has done so. J’ai y donné ma jeunesse, he said. It is certainly so. One must sacrifice the other. Tolstoy’s unedifying household, the discomfort of Rodin’s rooms: it all points to the same thing: that one must choose either this or that. Either happiness or art. On doit trouver le Bonheur dans son art … R. too expressed it something like that. And indeed that is all so clear, so clear. The great men have all let their lives become overgrown like an old road and have carried everything into their art. Their lives are stunted like an organ they no longer need.

…You see, Rodin has lived nothing that is not in his work. Thus it grew around him. Thus he did not lose himself; even in the years when lack of money forced him to unworthy work, he did not lose himself, because what he experienced did not remain a plan, because in the evenings he immediately made real what he had wanted during the day. Thus everything always became real. That is the principal thing – not to remain with the dream, with the intention, with the being-in-the-mood, but always forcibly to convert it all into things. As Rodin did. Why has he prevailed? Not because he found approbation. His friends are few, and he is, as he says, on the Index. But his work was there, an enormous, grandiose reality, which one cannot get away from. With it he wrested room and right for himself. One can imagine a man who had felt, wanted all that in himself, and had waited for better times to do it. Who would respect him; he would be an aging fool who had nothing more to hope for. But to make, to make is the thing. And once something is there, ten or twelve things are there, sixty or seventy little records about one, all made now out of this, now out of that impulse, then one has already won a piece of ground on which one can stand upright. Then one no longer loses oneself. When Rodin goes about among his things, one feels how youth, security, and new work flow into him continually from them. He cannot be confused. His work stands like a great angel beside him and protects him … his great work!…

+

FURTHER READING

For the monograph on Rodin that Rilke would eventually write, click here.

For selections from “Rilke’s Rodin”, an essay by William H. Gass, click here, here, here, and here