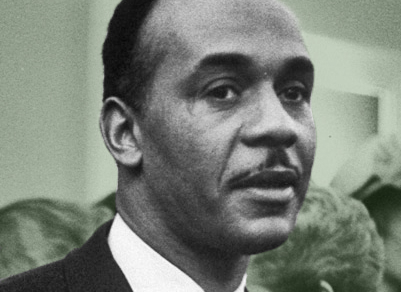

Ralph Ellison writes to his close friend and fellow writer Albert Murray. Murray was an Air Force pilot; he attended Tuskegee Institute with Ellison. Ellison here writes about preparing Invisible Man for publication, about the difficulty of transitions, and about Murray’s work.

New York

June 6, 1951

Dear Murray,

I hope you get this before you start your hitch. Your news was a surprise, to say the least. I was expecting to look up and see the three of you any old day. It makes me kinda sorry that I didn’t carry through during Nov. (?) when I called you and was all set to take a quick run down there. As luck would have it, it was during a big blizzard and you couldn’t be reached—and I fell back into my old groove and decided that I’d better remain here and work. Besides, I would have had to borrow the dough. Come to think of it, that was probably my last chance to see you in your natural habitat; after Invisible I’m just apt to be persona non grata—though I hope not. Anyway, I was having a little difficulty about that time and thought that such a trip might help, but I got over it and went on to turn in the book during April having finished most of it at Hyman’s place at Westport. I went there just about the time Shirley was doing the page proofs of Hangsaman and it was just the spur I needed. I had been worrying my ass off over transitions; really giving them more importance than was necessary, working out complicated schemes for giving them extension and so on. Then I read her page proofs and saw how simply she was managing her transitions and how they really didn’t bother me despite their “and-so-then-and-therefore”—and then, man, I was on. What I needed to realize was that my uncertainty came from trying to give pattern to a more or less raw experience through the manipulations of imagination, and that the same imagination which was giving the experience new form, was also (and in the same motion) throwing it into chaos within my own mind. I had chosen to recreate the world but, like a self-doubting god, was uncertain that I could make the pieces fit smoothly together. Well, it’s done now and I want to get on to the next.

Erskine and I are reading it aloud, not cutting (I cut out 200 pages myself and got it down to 606) but editing, preparing for the printer, who should have it in July or August. I’m afraid there’ll be no publication until spring. For while most of the reader reactions were enthusiastic, there were some stupid ones and Erskine wants plenty of time to get advanced copies in the hands of intelligent reviewers—whatever that means I guess it’s necessary, since the rough stuff: the writing on the belly, Rinehart (Rine-the-runner, Rine-the-rounder, Rine-the-gambler, Rine-the-lover, Rine-the-reverend, old rine and heart), yes, and Ras the exhorter who becomes Ras the destroyer, a West Indian stud who must have been created when I was drunk or slipped into the novel by someone else—it’s all there. I’ve worked out a plan whereby I trade four-letter words for scenes. Hell, the reader can image the four-letter words but not the scenes. And as for MacArthur and his corny—but effective—rhetoric, I’ll put any three of my boys in the ring with him any time. Either Barbee, Ras, or Invisible could teach that bastard something about signifying. He’d fade like a snort in a windstorm.

Who knows, perhaps we’ll have books published in the same year. I’m anxious to see what you’ve done and I’ve already told Erskine that you expect to have it typed by September. Come to think of it our writing novels must surely be an upset to somebody’s calculations. Tuskegee certainly wasn’t intended for that. But more important, I believe that we’ll offer some demonstration of the rich and untouched possibilities offered by Negro life for imaginative treatment. I’m sick to my guts of reading stuff like the piece by Richard Gibson in Kenyon Review. He’s complaining that Negor writers are expected to write like Wright, Himes, Hughes, which he thinks is unfair because, by God, he’s read Gide! Yes, and Proust and a bunch of them advance guard European men of letters—so why can’t those prejudiced white editors see it in his face when he goes in with empty hands and asks them for a big advance on a book he’s thought not too clearly about? No, they start right out asking him about Wright-Himes-Hughes, with him sitting right there all cultured before them, fine sensibilities and all. The capon, the gutless wonder! If he thinks he’s the black Gide why doesn’t he write and prove it? Then the white folks would read it and shake their heads and say, “Why, by God, this here is really the pure Andre Richard Gibson Gide! Yes, sir, here’s a carbon copy!” Then all the rest of us would fade away before the triumph of pure, abstract homosexual art over life. Right now, poor boy, he demands too much; not only must the white folks accept him, recognize him, as a writer, they must recognize him as a particular type of writer—And that, I believe, is demanding too much of the imagination. Especially if it must be backed up with an advance…. No, I think you’re doing it the right way. You’ve written a book out of your own vision of life, and when it’s read the reader will see and feel that you have indeed read Gide and Malraux, Mann and whoever the hell else had something to say to you—including a few old Mobile hustlers and whore ladies, no doubt. You’ve got to get it done by September—hell, I say this is only the point of departure, you can highball and ball the jack and apple jack in the next one, when you tell them about that philosophical, prizefighting foot racing, chippy chasing, Air Force character you’re going to meet up with in the next twenty-one months, name of Little Buddy.

Kidding aside I’m glad you’ve worked the hitch in with your larger plan in that you and Mozelle are getting that dream house. You’ve done so much since my days down there that I feel like a rounder. I never had much sense of competition (or at least I have a different kind) but with middle age staring me in the face I’m feeling that need to justify myself, or at least Fanny’s working and my thinning hair. So I’m trying to get going on my next book before this one is finished, then it it’s a dud I’ll be too busy to worry about it. I could use a little money, though, I really could. Anyway, just to put that many words down and then cut two hundred pages must stand for something. I’ll get you an advance copy if possible. Erskine’s having a time deciding what kind of novel it is, and I can’t help him. For me it’s just a big fat ole Negro lie, meant to be told during cotton picking time over a water bucket full of corn, with a dipper passing back and forth at a good fast clip so that no one, not even the narrator himself, will realize how utterly preposterous the lie actually is. I just hope someone points out that aspect of it. As you see I’m more obsessed with this thing now than I was all those five years.

Let us know where you’ve stationed should you transfer from Keesler and we’ll be glad to see you, as always, the first time you can hitch a flight up here. We might go to Chicago during August but we’re not certain. Meanwhile get the book finished. I want to learn more about Little Buddy and ole Reynard, the more than life-size man-with-the-plan. Give our love to Mozelle and Mike.

Ralph