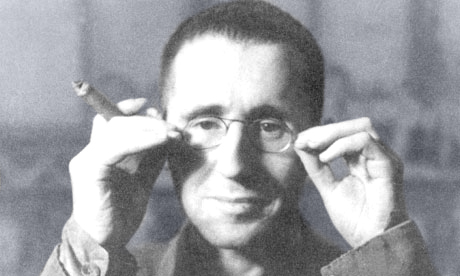

In this letter, Bertolt Brecht writes to Bernard von Brentano about an unfavorable review of Brecht’s book, The Threepenny Novel. The review had been published in the communist monthly, Unsere Zeit. Brecht explains his view of Stalin and the political changes in Russia.

Dear Brentano,

Thank you for your letter. Your sentence about the advantages of monitoring seems to mean that the K[antorowicz] review is an unfortunate accident and that the monitor has hastened to tell me about it. So while awaiting rectification, let’s forget about the review. The sentence provoked by this incident also suggests a certain resentment against supposedly free opinions and evaluations such as Kantor[owicz]’s. Furthermore, to come to the point that is of importance to you, it contains microscopic particles of totally free criticism. I think you know I feel friendly towards you, and not just for the sake of your good looks, but also despite some of your cherished opinions. I share your doubts as to the validity of opinions professed by persons who without said opinions would suffer material loss. But you will agree with me that such opinions may nevertheless be sound. Sound as well as unsound opinions can be bought. I do agree with you about the possibility of substantial reservations with regard to personal opinions and judgements where great tasks are being carried out by a small number of people. In the organisation of great social changes it is necessary to on the one hand to make (and break) alliances in many quarters and to allow our like-minded allies considerable freedom in matters that have no bearing on the common aim. (The battle must somehow be won.) On the other hand, we must drastically restrict the freedom of opinion of a small nucleus. A party without strict discipline cannot enter into alliances. You tend, it seems to me, to forget how very limited the Rusian revolutionaries are in number and how small their social base is. And what an enormous class struggle they are engaged in. And how isolated the Russian industrial proletariat is, how much hatred and how many adversaries they must contend with in building their industry, from which they expect everything. Only this revolutionising of the productive process can solve all problems, the distribution of commodities, the relations of people to one another, the creation of individual freedom. (Creation, not preservation.) It is not possible to bring about a radical change of this kind without repressing those who resist it and in some measure those who favour it. Such repression, we see, sometimes takes on a private character. I do not share your opinion of Stalin. The adulation of the sycophants and that attacks of those who (voluntarily or involuntarily) have withdrawn from the Russian struggle obscure the picture. He is not a brilliant writer. His toleration of a certain deification argues bad taste. But liking to hear himself called ‘the great’ does not make him little. The assertions of the ‘bureaucracy’ also have a character of struggle. They are addressed to those who have no confidence, who do not believe in the Party leadership and the necessity of all the effort and hardship (without necessarily being better leaders themselves). And of these there are many. Just consider the makeup of the Russian population, the numbers of peasants, white collar workers, technical intelligentsia of all sorts, of workers, of those who have only recently become workers, etc. Even if you think I am wrong about all this—even then there is one fact that ought to take the ground from under your feet. Your fight against a bad form of state becomes a fight against the highest form of state thus far developed. How can you call the Bolsheviks fascists? Do fascists abolish the private ownership of the means of production? Do fascists establish and maintain the dictatorship of the proletariat? You might as well say that a few individuals, aided by a few policemen, have seized power by violence (in line with Dühring’s theses). Without a class base.

I know, Brentano, that if you start collecting arguments against these statements you will manage to refute them. E.g., there are contradictions between the interests of the various European proletariats, and some things are more important than others. Action requires an ability to handle contradictions.

I hope you will take this letter as it is intended, as a small labour of friendship.

[Brecht]

From Bertolt Brecht Letters, 1913-1956. Brecht, Bertolt, Ralph Manheim, and John Willett. London: Methuen, 1990.