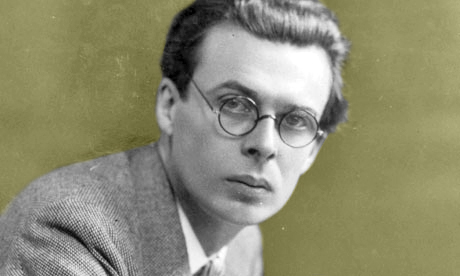

In a letter to his brother, evolutionary biologist Julian Huxley, Aldous Huxley recounts the political climate during his travels in South Asia with his wife, Maria.

To Julian Huxley

6 February, 1926

My dear J,

The enclosed cheque is to pay for the freight and insurance of two packages containing warm coats and bedding which I am sending home, as we shan’t need them (let us hope) in the tropics. Will you be kind enough to give them lodgment till we return. I have sent them carriage forward in order to stimulate the zeal of Thomas Cook, who is apt to be remiss if paid in advance.

Here we are on the high seas between Calcutta and Burma. Pleasant weather—a hot sun and a cool breeze, with practically no movement of the sea. We had an amusing fortnight at Delhi, in the midst of politics, which we had an opportunity of looking at from both sides—the government’s and the opposition’s. As people, I must say I preferred the opposition. Most of the Englishmen are of the export variety one rarely meets at home—at any rate in one’s own monde: rich, vulgar jute manufacturers, representing the European community in the Legislative Assembly, and then the officials—decent fellows, but terribly insect-like, as Civil Servants generally are. The Swarajists are more entertaining and various. There is Pandit Motilal Nehru—a superb old man of the world, positively dix huitième in polish and aristocracy: there are the Mohammedans, the Ali Brothers and Kidwai—wild passionate creatures: there is young Goswami, the treasurer of the party, a millionaire with an income of 80,000 pounds a year; and all the rest, a most varied assemblage. But what a farce the Assembly is. The statistics show that less than one per cent of the resolutions passed by the Assembly are given effect to by the government. Such are the Reforms. One isn’t surprised to find that the Indians are rather depressed. The government holds all the trump cards and shows no sign—naturally enough—of surrendering them.

We spent 3 days in Calcutta, and went one afternoon to Sir J. C. Bose’s institute. He showed us round for 3 hours and we saw all the experiments in full blast—the heart beats of plants, plants being drugged and recording their symptoms automatically in a graph, and so forth. Really astonishing. I had been skeptical—such is the force of ancient prejudice—I thought there must be something fishy about the results. But when you see the plants making records of their own sensations—well, you’ve got to believe. And I suppose one’s also got to believe Bose’s earlier results on the fatigue of metals and the effects of drugs on them. The results were published in 1900. Why haven’t they been more used than they have? Is it that people don’t believe—or what? If they’re sound, it does seem to be an experimental proof of what, by deduction, one had supposed to be true—that life is implicit in all inanimate matter. Bose is just about to start for Europe I expect you’ll see him and his experiments—if he brings his apparatus.

Love to all from both of us.

A.

P.S. Maria asks if Juliette will kindly open the packages when they arrive and send the fur coats and (if she thinks it necessary) the blue greatcoat to be cleaned, so as to make sure of eliminating any moths. Beware when opening, as the box is full of pepper and formalin.