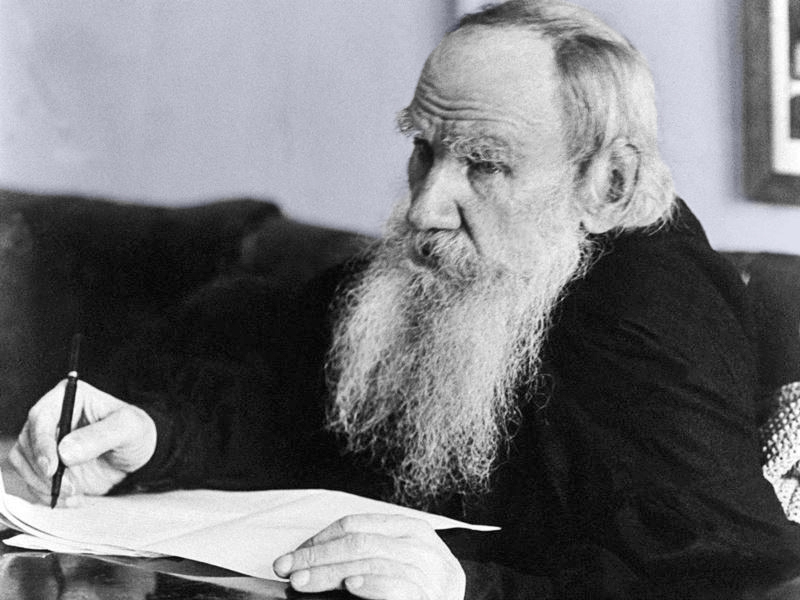

In the letter below, Leo Tolsoy writes to philosopher, publicist and literary critic (and longtime friend) N. N. Strakhov about Strakhov’s poetry and his own interest in the ‘physiology of delusions.’

Tula(?), 5 September 1878

Dear Nikolay Nikolaich,

While waiting for a letter from you I meant to forestall you so that you should find a letter from me in Petersburg, but I still haven’t got into the swing of the winter’s intellectual work and I haven’t managed to because of hunting, croquet and guests. Thank you for your letter and for your visit to us and for your unfailing friendship. I didn’t say anything to you about your poems. I didn’t like them. I don’t understand anything about poems, you know, and even you yourself don’t take them very seriously, so don’t be angry with me on that account. Your letter is all interesting, but the most interesting thing of all for me was Kavelin’s opinion which you had copied out about your book.

It’s impossible to devise any worse tortures on this earth than to make a man write and express with the utmost effort all the depth and complexity of his ideas and at the same time to make him read, as the opinions of an authority, such pronouncements as those of Kavelin. If I were tsar, I would make a law that a writer who uses a word whose meaning he can’t explain should be deprived of the right to write and receive 100 strokes of the birch. From the beginning you analyse things and demonstrate that people who say certain words invariably mean such and such by them; but Kavelin considers that your opinion is not binding for him, and that science rejects dualism. And nobody says that Kavelin is either an unscrupulous man or a madman, but everyone says: Kavelin is a philosopher. Your profession is a difficult, thankless and painful one, but he who endures to the end will be saved. Kavelin’s argument that Strakhov is wrong because he thinks (if I understand him correctly) that all science rejects dualism is the same as the argument that it is incorrect that a husband and wife are two separate people, because the church recognises them as one.

Again, if I were tsar, I would give 100 strokes of the birch to a person who uses the very popular argument, common to learned books, namely: according to my researches and observations, i.e. according to science, it turns out that a mushroom is a mushroom but a horse is a horse, that a body is a body but a soul is a soul, electricity is electricity but heat is heat, and therefore the legitimate conclusion according to science would be that things are different, but according to my secret desire (and according to the purpose of science) it would be better if everything were one. And then the following jump is mad: science, science itself is left aside, and the course of science, the history of science is brought into the reckoning, as if the future course of science could be intelligible to the man who knows no science; and it is assumed that only some little trick is needed to achieve what we desire.

Forgive me for jabbering about something you understand better than I do, but I’m so fond of studying the physiology of delusions that I can’t help it. I’m truly glad and proud that my advice to you to write your life interests you. I’m very interested to know how it has been taking shape. I would have to tell you too much that was flattering order to explain why it was actually you I advised to do this. Your poems have precisely the good in them that I expect from your confession.

Our children have been ill, the older one with tonsillitis and Seryozha with pleurisy; they are getting better.

Turgenev has been again and was just as nice and brilliant, but—between ourselves, please—rather like a fountain of piped water. You were afraid all the time that he would soon run out and dry up. As soon as you had left, we sat down at the table and I said: ‘well, go on and abuse him’. I wish you could have heard Tatyana Andreyevna’s tone of voice when she said: ‘it’s impossible now’ and heard the general chorus of assent and seen my feeling of self-satisfaction at this, as if it were something credible on my part God grant you may get on with your difficult philosophical work, and in such a way that it will satisfy you more from within than from without. Wish me the same. I very much want to write and I’m gradually making a start.

I wrote to Stasyulevich to say that I have entrusted everything to do with The Russian Library to you.

FURTHER READING

For a recent essay at Slate on Tolstoy’s admiration for the Doukhobors, a remote pacifist sect in the highlands of Georgia, go here.