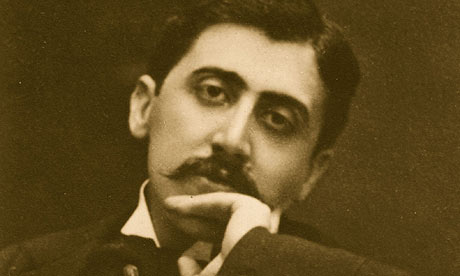

Marcel Proust

Marcel Proust

Below, Marcel Proust shares with writer and critic Camille Vettard some reflections on his method and craft. The letter is dated to “early October, 1922.”

Mon cher ami

I should like to answer your questions at length, but I am practically dead, and my reply would be almost the votive offering of a dying man. What I should like people to see in my book is that it sprang wholly from the application of a special sense (at least that is what I believe), which is very difficult to describe (like trying to describe sight to a blind man) to those who have never exercised it. But that is not true of you and you might understand me if I merely give you the (very imperfect) simile (you will certainly find a much better on yourself), which seems to me the best (at least at present time) to explain what this special sense is. It is perhaps like a telescope, which is pointed at time, because a telescope reveals stars which are invisible to the naked eye, and I have tried (I don’t however, attach any special value to my simile) to reveal to the conscious mind the unconscious phenomena which, wholly forgotten, sometimes lie very far back in the past. (It is perhaps, on thinking it over, this special sense which has sometimes made me concur with Bergson—since it has been said that I do—for there has never been, insofar as I am aware, any direct influence.)

As to style, I have endeavored to reject everything dictated by pure intellect, everything that is rhetoric, embellishment, and, more or less, any deliberate or mannered figures of speech (those figures which I denounced in the preface to Morand’s book) to express my deep and authentic impressions and to respect the natural progress of my thought. I am saying this all very poorly because I am forced to dictate in terrific pain, which leaves me only strength enough to tell you again of my admiring and grateful affection.

Marcel Proust

+

FURTHER READING

For René Girard on Proust’s “special sense,” click here and here.

For a short, incisive piece on Proust and Bergson, click here.

From Proust’s preface to Paul Morand’s Tendres Stocks (mentioned above; trans. by Ezra Pound):

The truth (M. France knows it better than anyone, for he knows everything better than anyone else) is that from time to time a new and original writer arrives (call him if you like Jean Giraudoux or Paul Morand, since for some reason unknown to me, people are always bringing Morand and Giraudoux together like Natoire and Falconet in the marvelous Nuit à Châteauroux, without their having any resemblance). This new writer is usually fatiguing to read and difficult to understand because he joins things by new relationships. One follows the first half of the phrase very well, and then one falls. One feels it is only because the new writer is more agile than we are. New writers arrive like new painters. When Renoir began to paint people did not recognize the objects he presented. Today it is easy enough to say that he is an eighteenth-century painter. But in saying it one omits the time factor, and it needed a great deal of time, even in the nineteenth century, to have Renoir recognized as a great artist. To succeed, the original painter, the original writer, proceeds like an oculist. The treatment—by their painting, their literature—is not always agreeable. When they have finished they say: “Now look!” And there it is, the world which has not only been created once, is created as often as a new artist arrives, appears to us—so different from the old one—perfectly clearly. We adore the women of Renoir, Morand, or Giraudoux, whom before the artist’s treatment we refused to consider as women. And we want to walk in the forest, which on the first day had looked to us like anything you like, except a forest—for example a tapestry with a thousand nuances, and lacking exactly the nuances of forest.