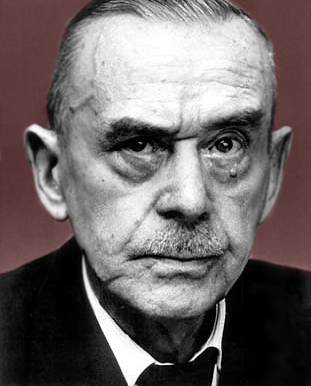

In the letter below, Thomas Mann rejects the notion that The Magic Mountain is hostile to life, instead arguing that he has attempted “to make death a comic figure.”

To Josef Ponten

Munich

February 5, 1925

Dear Ponten:

Your last Magic Mountain letter, dated the 2nd, reached me today—a document that can truly in the finest and purest sense of the word be called “naïve.” I sincerely thank you for it. Of course I don’t doubt your explanation that you wrote it before reading my reply to your last letter, whose naïveté was of a somewhat less fine character. But my faith goes a step further: I believe you would have written no differently even after reading that letter. Take this statement as the moral compliment it is. Today I have given a good deal of thought to the things you say, in sadness and admonition, about the inner nature of the book. We must take this nature, the alliance with death that you scent, the melancholy that depressed you (although betweenwhiles you had to laugh aloud—a strange complication and confusion!), the skepticism and nihilism which is (or so I think) the final effect of the disputes—we must take all this as something imposed by destiny, I suppose, a personal fatality which evidently emerges from my work. Hardly likely that anything can be done about it. You now know better than before how, where, in what sphere, under what humanly not wholly secret inner circumstances, this well-balanced and not humorless, though sometimes irritable and fatiguable Herr T. M., honorary doctor and paterfamilias, really dwells, and henceforth you will subject your relations with him, if you continue them at all, perhaps somewhat more than previously to the rule of discreet forbearance.

But let’s be just in the matter of hostility toward life. Is not my book, despite its own inner fatality, a book of good will? In saying this I leave aside the question of whether the kind of nihilism that pokes fun at extremist theories and manages to counter them with such characters as the brave Joachim and the high and mighty stammerer Peeperkorn (the age provides nothing better)—is really such dyed-in-the-wool nihilism, after all. This is just by the way. But where in all the history of art and literature have you ever before encountered the attempt to make death a comic figure? That is literally done in The Magic Mountain, and our good Hans, though by nature inclined to consider death as the most noble and superior principle, is systematically disillusioned on that score, however piously he fights against it. Is that hostility to life? I feel that it at least testifies to the intention of denying such hostility. Nor is it accurate to say that Hans Castorp learns nothing at all, arrives at no resolution and no decision in his sorry place. In his dream in the snow he sees this: Man is, to be sure, too superior for life; let him therefore be good and attached to death in his heart. But man is also and especially too superior for death; let him therefore be free and kind in his thoughts. This insight into the human incompatibility of aristocratic alliance with death (history, romanticism) and of democratic amity toward life is not something that Hans bears “triumphantly home on the point of his hunting spear,” as [literary critic, Conrad] Wandrey (who in other respects also is not so sound) writes. On the contrary, Hans promptly forgets it again; in general he is not personally able to cope with his higher thoughts. But how does he come to be concerned about “man” and man’s “standing and status” at all? Primarily not through Naphta and Settembrini, but rather in a far more sensual way which is suggested in the lyrical and enamored treatise on the organic in nature. You found the section too long, but it is not an arbitrary digression. Rather, it shows how there grows in the young man, out of the experience of sickness, death, and decay, the idea of man, the “sublime structure” of organic life, whose destiny then becomes a real and urgent concern of his simple heart. He is sensuously and intellectually infatuated with death (mysticism, romanticism); but his dire love is purified, at least in moments of illumination, into an inkling of a new humanity whose germ he bears in his heart as the bayonet attack carries him along. His author, who there takes leave of him, is the same who emerged from the novel to write the manifesto “The German Republic.” He is no Settembrini in his heart. But he desires to be free, reasonable, and kindly in his thoughts. That is what I would like to call good will, and do not like to hear branded as hostility to life.

Wandrey is priceless. He denies me creativeness, music, sculptural quality, in short everything, and does so with the greatest deference. It is difficult to take any kind of attitude toward that sort of thing. And how he treats me as a kind of shuffling old wizard. “The pastmaster.” “Oh, that cunning old puppetmaster.” I had to laugh aloud. But I shall thank him nicely; he has taken great pains.

Early in March I am going traveling […]: Venice, Corfu, Constantinople, Port Said, Naples, Algiers. On invitation from the Stinnes Liune. Perhaps we can see each other some time before then. Frau Hallgarten [philanthropist and patron of the arts] recently spoke of inviting us together.