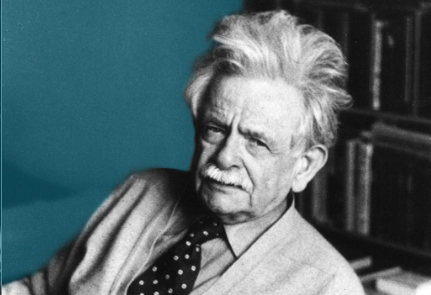

Below, Elias Canetti’s response to his brother’s (apparently trenchant, generally positive) criticisms of Auto-da-Fé. Elias Canetti was thrilled with the novel’s overwhelmingly positive reception, confiding to Georges: “ Since the publication of Auto-da-Fé, everyone who reads it considers me one of the most important writers of our time, and I admit that, given the enormity of my craving for fame, I am not indifferent to this […] I do not want to die, and fame is for me only one of the most obvious paths to immortality.”

TO GEORGES CANETTI

December 5, 1935, Vienna

My dear, dear Georg,

Two weeks have passed since I started this letter to you. Perhaps I only left it unfinished because I wasn’t pleased with the tone I had set. It’s just that I can’t tell you how happy and excited your double recovery makes me. Nor do I have any desire to talk about your experience up there in the mountains. I was so shaken by your illness that I would have liked to squeeze your hand tightly and tell you: Georg, you are even more of a brother. Now you are my brother forever, for you know what death is and will no longer smile at my rabid tirades against it. I would love to be with you. In the next two years, I shall be working on the most daring book ever written; it is a book against death that I’ve been thinking about for eight years or more. I would have loved to write it while living with you, because I love you so much and half a year ago was trembling for your sake. But I fear it won’t be possible. Perhaps, if I’m lucky (I mean material luck—some dough), I can really come visit you for a month. Otherwise, you’ve got to come to Vienna.

What you have to say in general about my (latest) book is very wise. You have completely grasped the essence of the automatism I intended to portray. In fact, of all the readers who have commented upon it, you are the sharpest. But you have underestimated the lucid consciousness with which I did it. Naturally, it is only for the sake of the automatism that I turned to the psychotics. In a letter I wrote to Thomas Mann four years ago, I explained my plan to base a “comédie humaine” on psychotics, and used literally the identical wording you use in your letter. (With the one difference that at the time, Joyce was only a name to me. My notion of his work was extremely vague, so I couldn’t measure my project against his.)—But you are mistaken in the details: you could only have formed the impression of excessive erudition because you were anticipating the final chapter, especially the great debate between the two brothers. No doubt part one and part three contain too much erudition when placed immediately side by side. But for the average reader, the longer part two stands between them and leads very far away from all that erudite ballast. Besides, there’s something particularly attractive about clarifying the structure of madness with the help of learned, foreign, quasi-objective building blocks. The “automatism” becomes clearer; it has something of the advantages of a puzzle or a chemical formula that you memorize in the same way.—I myself am disturbed by the frequent scenes of beatings. I’m sure they disturb you even more. They stand for something other than beatings: perhaps for all hurtful words, perhaps (and this seems even more likely to me) for the hundreds of thousands of attempted murders everyone alive is constantly exposed to.—In one point, however, your misunderstanding is much more profound: perhaps the most important thing about the book for me is the way the characters talk past each other. It may seem exaggerated sometimes, but that is only because old, bad novels have gotten us used to people understanding each other. That, however, is one of our silliest illusions. In reality, no one understands anyone else. It amounts to a miracle if once in a great while it happens after all. The nonstop mutual understanding that goes on in old-fashioned novels is kitsch. When I differentiate my characters, even in their speech, so sharply from each other, all I’m doing is raising an utterly normal element of our lives as individuals to an aesthetic principle.

The reviews have been excellent so far. I sent Mama one from the Neue Freie Presse and I’m sure she has shown it to you too. But perhaps with the exception of Thomas Mann and two local writers, Dr. Sonne and Dr. Sapper (and you of course), I can say that hardly anyone has really understood the book. It makes an enormous impression on people. It impacts them in about the same way as someone hitting them over the head with a club. Some of the reviews seem to be written by people who have been drugged. But what does it matter?

The fact remains: since the publication of Auto-da-Fé, everyone who reads it considers me one of the most important writers of our time, and I admit that, given the enormity of my craving for fame, I am not indifferent to this. Maybe it’s unwise of me to say it out loud, but you know me well enough in any event: I do not want to die, and fame is for me only one of the most obvious paths to immortality.—It may interest you to know what Thomas Mann said about Auto-da-Fé. In a long, handwritten letter, he says that my novel and a book by his brother have preoccupied him more than any other new books this year. After going into great detail, he summarizes his impression as follows: “I’m really struck and very positively impressed by its eccentric abundance, overflowing imagination, a certain embittered grandiosity of its plan, its poetic courageousness, its mournfulness, and its daring. It is a book that can stand beside the works of the greatest talents of other literary cultures, in contrast to the stuffy mediocrity common in Germany today.”—In this judgment, you have to make some allowances for Thomas Mann’s natural reserve and somewhat dry disposition. He is so completely and utterly lacking in effusiveness that the words above can almost be taken as effusive. And that is how all the experts take them. I hope you are not annoyed at this long gush of self-congratulation. I’ve written you this to spare you the somewhat silly reviews, however much they may sing my praises. I won’t send you any unless they are intelligent enough to take halfway seriously.

+