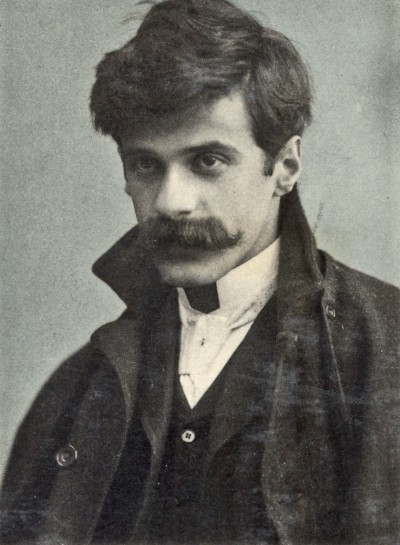

Photographer and gallery owner Alfred Stieglitz writes to the famed American artist Georgia O’Keeffe, making reference to the summer of 1918 when he invited her to move to New York in order to live with him and create art full-time. Stieglitz, 23 years her senior, was married, and did not finalize the divorce of his first wife until 1924. At the time of this letter’s writing, he was spending a summer at his family home in Lake George, depressed and discouraged after being informed of the slated destruction of the building that had housed his gallery, “The Intimate Gallery,” which Stieglitz called “the Room.”

Lake George

5 August 1929

Noon. It’s an autumn day — cold. And a stormy gray very moving sky. Amazing tempting shapes. I have been up since seven and very much on the go. Getting off many letters — at least seven to bankers who will insist in sending checks to you with O’Keeffe spelled wrong. I have written before but somehow mistakes continue. Many details to be attended to. I’ll change much when I go to New York. It may cost money but my time does mean more than money.

I want to print this afternoon. Maybe I have something very fine. I don’t know.

Two letters from my woman finally came. Very grand ones. It was a very long wait.

Yes, you are doing as I want you to do. Just wired you. Fill yourself to the fullest. I understand.

And I share it all with you. I have much more in me of what you are experiencing than you have any idea of. There is a side of me that is as wild as your wildest side is, but my life in America has been such I had to find “Equivalents.” Someday we’ll talk it all over without arguing. There is nothing to argue when one sees. It’s all very simple. No you are not selfish.

When I telegraphed you the other day there was nothing in the East for you but myself, I well knew what I was saying. Of course if you were a water woman the sea would have the parallel of what you are getting on land.

What you feel beyond you is in your blood — what I feel beyond me is in the center of me, my blood, too. Twenty-five years in a way make a difference. And man and woman are complementary.

The mail brought me a very unusual bunch of letters. Much is asked from me, spiritual and practical. Maybe now that finally our togetherness is reestablished and that fine edge that both insist on again exists, I can be of some use to others. But I’ll have to spare myself. Something I never did before.

There has been so much “waste” that it is ghastly. I dare not waste any more.

It does feel very wonderful to know we are together again, that your need and my need are identical, even though you are there and I am what is termed “here.” I know the pull I have, your pull towards me. But you are wise in doing what you are doing. Of course I want to hold you and kiss all of you, see you, look at you, see whether you really exist, are what I know you to be. Too bad I’m not twenty years younger and yet be what I am now! But then perhaps we wouldn’t be together at all. That’s the queer thing about it. It’s great you’re riding so much. Great you’re doing all the things you are doing. All so healthy and clean. Riding in the storm. That reminds me of some days years and years ago up in the Alp and in my little scull out on the Lake here when I was a kid, in real storms. I had no fear then, no responsibilities. That damnable sense of responsibility — developed to a morbid degree! I’m gradually ridding myself of the morbid state. Yes, I am. I’m doing lots of things to myself. Nothing that isn’t natural. I have to in order to go on.

Painting! I wonder what I’ll see. I really wonder will I be able to see paintings at all. Yours surely. Marin’s too. But not many others. What’s more I don’t want to see them. As much else I don’t want to see or touch.

You grand woman. You say you are my woman. Yes I know. On August 9 it will be eleven years that you gave me your virginity. During thunder and lightning. It’s as if it were yesterday. It’s a wonder I didn’t give you a child! We were made to have one. But it was not to be. I realize how impossible such a child’s chance would have been. How unready you were to be. How little I could provide for it and for you. Yes, you gave me your virginity, I still your face and feel it all. And see you on the floor afterwards naked with a bandage on — a wounded bird. So lovely. Georgia, I loved you then most wonderfully and I never ceased to love you in spite of all you felt to the contrary. But what I feel today is what you feel beyond you. That’s what you feel beyond yourself — that something you are to me. You gave me your virginity. That’s the reason you are my woman for all time. You are not like other women and I am your man for all time for I’m not like other men.

You gave me your virginity, Georgia, and don’t I remember June 15 — six days after you arrived — and I touched a spot and you jumped and I sat on a chair and felt like a murderer and you wondered what ailed me. I often wondered since wasn’t I a murderer. Particularly after you had gone and you wrote me those letters and I looked at the hair I cut that day and I looked long. And I knew that what I was and felt was as true as that day — that touch, that hair. And as fine. And then I was called to camp to see Kitty and her mother and slept in a tent, storm raging, a boy asleep near me, you in Lake George. I remember the long talk with Emmy and Kitty listening. And when I went away I believed I was understood. Really did. And it was the day returning to the Lake you gave me your virginity. I couldn’t have accepted it (or taken it) hadn’t I felt all was very right between Kitty, Emmy and me. You know how “wrong” I eventually was. But your virginity was in my trust. Is today. And I have never forgotten it. Yet you doubted me. Appearances were against me.

And I bungled, for I was hurt as you were hurt. But all it very right between us, for you gave me your virginity. It is the very center of your being you gave me and dearest of women, most beautiful of women, I gave you my center. The center of my center. No one else ever received it. Yes, I love you.

How the trees are torn to pieces by the wind — a gale — and the sky has grown very dark and the room is very cold. I don’t want to start a fire.

This morning I had a touch of sinus. If it develops I’ll go to town and have it nipped in the bud. I hope it won’t be necessary. The sudden crass change of temperature — and I flaunting all of myself to the wind! Getting chilled. And the bed was icy. And my wrapper is still in the trunk. I’ll tell you a secret. I couldn’t wear it while I felt you no longer loved me! What you were feeling in a way about me I was feeling in a way about you. Only I didn’t have the bitter resentments. But the line was very similar.

Maybe I’ll get out the wrapper. Maybe on August 9th (and be sentimental). No, no, I’m not a bit sentimental. And yet I am.

I love you, my wild Georgia O’Keeffe. I’ll never be able to hold you again. So I fear. But I really don’t fear. It looks like snow. Nothing can surprise me. Oh yes, something can. You. Beautiful surprises only.

Lunch calls.

Give me your body, let me kiss every inch of it, long and tenderly. Remember you gave me your virginity. It still exists. I kiss it — a kiss into eternity. Do you feel it? I know you do.

And still another kiss.

From My Faraway One: Selected Letters of Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011, pp. 505-507.

FURTHER READING

Listen to excerpts from O’Keeffe’s and Stieglitz’s letters at NPR Books.

Look at photos of O’Keeffe taken by Stieglitz, about which she said, “I felt somehow that the photographs had nothing to do with me personally.”

Read Bitch magazine’s retrospective on O’Keeffe’s attempt to disassociate herself from female iconographists.