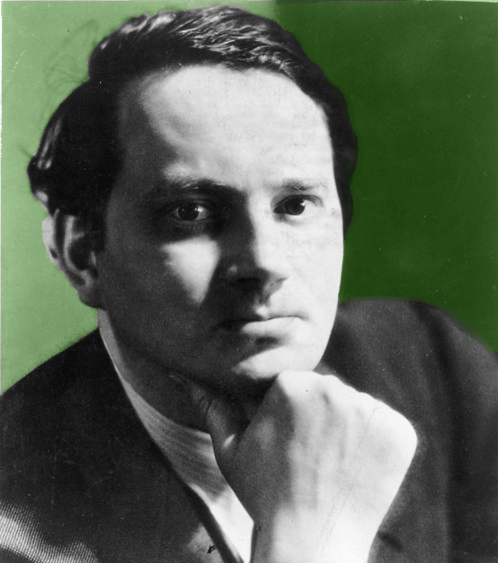

Thomas Wolfe

Thomas Wolfe

Below, Thomas Wolfe recounts for Aline Bernstein his (drunken, hapless, violent) experience of Oktoberfest in Munich, which resulted in “a mild concussion of the brain, four scalp wounds, and a broken nose,” as well the (ultimately unfounded) fear that he’d accidentally killed a person.

To ALINE BERNSTEIN

October 4, 1928, Munich

Dear Aline:

…Today is the first time I have been for mail since Saturday. I went to the hospital Monday and got out this afternoon. I had a mild concussion of the brain, four scalp wounds, and a broken nose. My head has healed up beautifully, and my nose is mending rapidly…. I am shaven as bald as a priest—in fact, with my scarred head, and the little stubble of black hair that has already begun to come up, I look like a dissolute priest.

What happened I am too giddy to tell you about tonight. I shall begin the story and try to finish it tomorrow. I had been in Munich three weeks—during that time I had led a sober and industrious life—as I have since coming abroad. It is now the season here of the Oktoberfest. What the Oktoberfest is I did not know until a week or two ago when it began. I had heard of it from everyone. I thought of it as a place where all the Bavarian peasant people come and dance old ritualistic dances, and sell their wares, and so on. But when I went for the first time, I found to my disappointment only a kind of Coney Island—merry-go-rounds, gimcracks of all sorts, innumerable sausage shops, places where whole oxen were roasting on the spot, and enormous beer halls. But why in Munich—where there are a thousand beer-drinking places—should there be a special fair for beer? I soon found out. The Oktober beer is twice as strong as the ordinary beer—it is thirteen percent—the peasants come in and go to it for two weeks.

The fair takes place in the Theresien Fields which are on the outskirts of the town, just before the Ausstellungs Park…. I went out to see the show two or three times—these beer halls are immense and appalling—four or five thousand people can be seated in one of them at a time—there is hardly room to breathe, to wiggle. A Bavarian band of forty pieces blares out horrible noise, and all the time hundreds of people who cannot find a seat go shuffling endlessly up and down and around the place. The noise is terrific, you can cut the air with a knife—and in these places you come to the heart of Germany, not the heart of its poets and scholars, but to its real heart. It is one enormous belly. They eat and drink and breathe themselves into a state of bestial stupefaction—the place becomes one howling, roaring beast, and when the band plays one of their drinking songs, they get up by tables all over the place, and stand on chairs, swaying back and forth with arms linked, in living rings. The effect of these heavy living circles in this great smoky hell of beer is uncanny—there is something supernatural about it. You feel that within these circles is somehow the magic, the essence of the race—the nature of the beast that makes him so different from the other beasts a few miles over the borders….

This is what happened… There is an American Church in Munich. It is not really a church—it is two or three big rooms rented in a big building in the Salvator Platz—a place hard to find, but just off the Promenadeplatz. They have six or eight thousand books there—most of it junk contributed by tourists. But you can go there in the afternoon for tea—if you are lonely you can find other Americans there… There was a young American there with his wife and another woman, his wife’s friend…. I was delighted to talk to these people; they asked about rooms, life in Munich, galleries, and so on…. I told them about the Oktoberfest, and suggested that they go there with me during the afternoon, as the good museums were closed. So we went out together: the weather was bad, it began to rain. There was a great mass of people at the Fair—peasant people in their wonderful costumes, staring at all the machines and gimcracks. I took them through several beer halls, but we could find no seats. Finally, after the rain had stopped, we managed to get in at a table some people were leaving. We ordered beer and Schweirswurstt…and I was beginning to desire only to get rid of these people, who were full of quotations from the American Mercury…. I was nauseated by them, I wanted to be alone. I think they saw this; they suggested we all go home and eat together; I refused and said I would stay there at the Fair. So they paid their share, and went away out of all the roar and savagery of the place.

When they had gone, I drank two more liters of the dark Oktober beer, singing and swaying with the people at the table. Then I got up and went to still another place, where I drank another, and just before closing time—they close at 10:30 there at the Fair, because the beer is too strong, and the peasants get drunk and would stay forever—just before closing time I went to another great hall and had a final beer. The place was closing for the night—all over the parties were breaking up—there were vacant tables here and there, the Bavarian band was packing up its instruments and leaving. I talked to the people at my table, drank my beer, and got up to go. I had had seven or eight liters—this would mean almost a quart of alcohol. I was quite drunk from the beer. I started down one of the aisles toward a side entrance. There I met several men—and perhaps a woman, although I did not see her until later. They were standing up by their table in the aisle, singing perhaps one of their beer songs before going away. They spoke to me—I was too drunk to understand what they said, but I am sure it was friendly enough. What happened from now on I will describe as clearly as I can remember, although there are lapses and gaps in my remembrance. One of them, it seems to me, grasped me by the arm—I moved away, he held on, and although I was not angry, but rather in an excess of exuberance, I knocked him over a table. Then I rushed out of the place exultantly, feeling like a child who has thrown a stone through a window.

Unhappily I could not run fast—I had drunk too much and was wearing my coat. Outside it was raining hard; I found myself in an enclosure behind some of the fair buildings—I had come out of a side entrance. I heard shouts and cries behind me, and turning, I saw several men running down upon me. One of them was carrying one of the fold-up chairs of the beer hall—it is made of iron and wood. I saw that he intended to hit me with this, and I remember that this angered me. I stopped and turned and in that horrible slippery mudhole, I had a bloody fight with these people. I remember the thing now with horror as a kind of hell of slippery mud, and blood, and darkness, with the rain falling upon us several maniacs who were trying to kill. At that time I was too wild, too insane, to be afraid, but I seemed to be drowning in mud—it was really the blood that came pouring from my head into my eyes…. I was drowning in oceans of mud, choking, smothering. I felt the heavy bodies on top of me, snarling, grunting, smashing at my face and back. I rose up under them as if coming out of some horrible quicksand—then my feet slipped again in the mud, and I went down again into the bottomless mud. I felt the mud beneath me, but what was really blinding and choking me was the torrent of blood that streamed from gashes in my head. I did not know I bled.

Somehow—I do not know how it came about—I was on my feet again, and moving towards the dark forms that swept in towards me. When I was beneath them in the mud, it seemed as if all the roaring mob of that hall had piled upon me, but there were probably not more than three. From this time on I can remember fighting with only two men, and later there was a woman who clawed my face. The smaller figure—the smaller man—rushed towards me, and I struck it with my fist. It went diving away into the slime. I was choking in blood and cared for nothing now but to end it finally—to kill this other thing or be killed. So with all my strength I threw it to the earth: I could not see, but I fastened my fingers and hand in its eyes and face—it was choking me, but presently it stopped. I was going to hold on until I felt no life there in the mud below me. The woman was now on my back, screaming, beating me over the head, gouging at my face and eyes. She was screaming out “Leave my man alone!” (“Lassen mir den Mann stehen”—as I remember). Some people came and pulled me from him—the man and woman screamed and jabbered at me, but I could not make out what they said, except her cry of “Leave my man alone,” which I remember touched me deeply….

These people went away—where or how I don’t know—but I saw them later in the police station, so I judge they had gone there. And now—very foolishly perhaps—I went searching around in the mud for my hat—my old rag of a hat which had been lost, and which I was determined to find before leaving. Some German people gathered around me yelling and gesticulating, and one man kept crying “Ein Arzt! Ein Arzt!” (“A Doctor! A Doctor!”) I felt my head all wet, but thought it was the rain, until I put my hand there and brought it away all bloody. At this moment, three or four policemen rushed up, seized me, and hustled me off to the station. First they took me to the police surgeons—I was taken into a room with a white, hard light. The woman was lying on a table with wheels below it. The light fell upon her face—her eyes were closed. I think this is the most horrible moment of my life…I thought she was dead and that I would never be able to remember how it happened. The surgeons made me sit down in a chair while they dressed my head wounds. Then one of them looked at my nose, and said it was broken, and that I must go the next day to a doctor. When I got up and looked around, the woman and the wheeled table was gone. I am writing this Saturday (six days later): if she were dead, surely by this time I would know….

Sunday morning. I do not think I have told you what happened to me after the police doctors had looked at my wounds and dressed them that night at the Oktoberfest—or how I found doctors to look after me, and so on. From the doctors I was taken before the police next door where they asked me many questions which I did not answer. They also had two of the other men there, looking very bloody, also—and perhaps others I did not see. Then they let me go, when they could get nothing out of me. I had lost my hat, and was one mass of mud and blood: it was raining hard and wet: a young man I did not know went along with me, and when I asked him what he wanted, he said he “had no role to play.” We got a street car and came back to the center of town where I got off and shook him—at the Odeonsplatz.

That day at lunch with the three people who had gone to the Fair with me, I had met a young American doctor who had come here for special study. Now I was going back to their place to get his address. I found the married pair in bed, and the other woman out with the doctor. They stood around and gasped and looked scared—the woman made me a cup of tea—and in a few minutes the woman and the doctor came back. He gave me the address of another American doctor who was working in a famous clinic here, and told me to see him the first thing the next morning.

I got a taxi and drove through town to the clinic. My appearance almost caused an earthquake in the pension, and people in the streets stared at me. I had been directed to Dr. Von Muller’s clinic—and Dr. Von Muller is one of the greatest doctors in the world. His picture was in all the papers the other day—on his seventieth birthday…. I found the great man in the office, and when I asked for his American assistant—Dr. Du Bois, whose name I had been given—I was told he was at home, and that I should go there. I felt low-spirited and was on the point of asking old Von Muller himself to look at my head (which would have been a great breach), when in came this man Du Bois. The name is French, but you never saw anyone more prim and professorly American. He was very tidy and dull-looking, with winking eyeglasses, and a prim careful voice. I felt done for. I told him what had happened and where I was hurt, and he listened carefully, and then said in his precise careful way that we ought perhaps—ah—to see what can be—ah—done for you. By this time, I thought I was dead.

But here let me tell you the truth about this man, Dr. Du Bois, who is, I found later, a professor in the Cornell Medical School (hence the professorly manner). He is one of the grandest and kindest people I have ever met. In this dry prim way he showed me for days the most amazing kindness—and then refused to accept anything for his services, although he had come to my pension with me in a taxi, to help me pack, when the German doctor said I had to come to the hospital, and had gone back with me, and had visited me once or twice a day, and brought me books during the time I was there in the hospital. At any rate, he asked the great Von Muller first of all where we should go, and the great Von Muller had said that we should go across the street to the Surgical Building and see the great Lexer, who is the best head surgeon in Germany.

+

FURTHER READING

For more on the Wolfe/Bernstein relationship, click here.