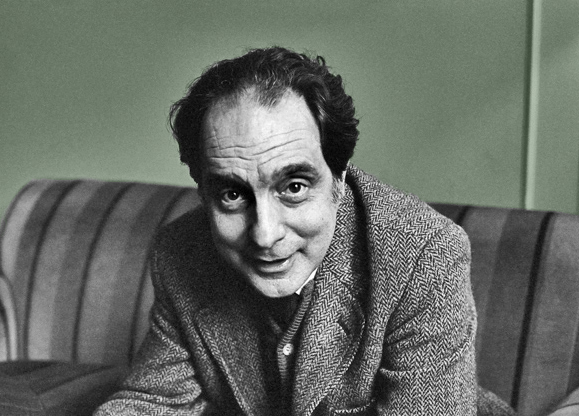

The son of anti-Fascist, secular parents, writer Italo Calvino joined the Communist Party in 1945 at the age of 22. In this letter to literary critic Mario Motta, Calvino rejects Motta’s suggestion that he read The God that Failed, a collection of essays about the failure of Communism, which was written by six former Party members. He goes on to discuss depictions of paradise by various authors and intellectual movements. Though he mocks the “dreary figure” of the ex-Communist in the letter below, Calvino himself would leave the Party in 1957.

To Mario Motta—Rome

Turin, July 1950

Dear Motta,

Your note on The God That Failed has prompted me to some considerations. I will not discuss the debate surrounding the book, which I have not read nor do I think I will read it. (The “ex-Communist” is one of the dreariest figures of the postwar period: behind him one senses that sad air of wasted time, and ahead of him the squalid existence of someone redeemed by the Salvation Army, going around the streets with the band and its choir, shouting out that he’s been a drunkard and a cheat.) What I’m interested in are the things you say about paradise:

In fact each one of us can hope for a supernatural paradise, without necessarily damaging either himself or others, but not for a paradise on earth: hoping for a latter means losing all real understanding of history, choosing a paradigm devoid of sense to evaluate history, condemning oneself voluntarily to never finding a homeland in which he doesn’t feel a foreigner sooner or later.

As often happens in such cases, before even formulating a verdict on your statement, I spontaneously asked an “auto-critical” question: what about me, do I believe in a paradise? But I had to struggle a bit to focus the question, to create an “image” of it for myself; all that came to mind were literary examples, second-hand ideas, things gleaned from elsewhere. I realized that this concept of a “paradise” that is—I won’t say supernatural, for I’m not accustomed to reflect on that plane—but even “terrestrial” was totally foreign to my usual way of thinking

I’ll try to go back to the specific case from which we started: how I “see” the revolution, socialism, the society I hope for and for which, “in my humble way,” I am working. What came to mind were images dictated by that small amount of experience I have of moments of democratic awakening and organized and efficient activity. I mean moments when interests in all aspects of life, communication with others, and ability and intelligence all increase in each of us; all this taken to the utmost degree and become non-provisional, but with effects that are anything but “paradisiacal”; a host of things to do, of responsibilities, of “troubles”: you are who are convinced I’m lazy, might laugh. What pushes me in this direction is not, it seems to me, a “paradise” to be reached, but the satisfaction of seeing things gradually start to go the right way, feeling in a better position for solving problems as they emerge, for “working better,” having greater clarity in my head and the sense of being more in my right place when I am amongst other men, amidst things, in the world of history.

Now I believe that this is a modern man’s achievement (or rather the achievement for which he should strive): to shed the myth of a teleological “paradise” (whether metaphysical or on earth) as man’s true homeland, and to find this human homeland instead in the heart of his own works and days, in a dialectic between himself and everything else that is extremely difficult to acquire and maintain. This is possible only for those who have very clear ideas on the direction they must be going in, for those who know—more and more clearly—what they want, what they must want; but more than the succession of points of arrival what counts is seeing the world being transformed by the little that each of us does, that each of us gets involved during the process of transforming it. That was why socialism emerged from “utopia” (from “paradise”) when it started to be a “science” and hence a “praxis”; for this reason the Communist fights even though he knows that the results of his sacrifices will be enjoyed only by future generations. That is why one cannot imagine a “contemplative” Marxist (ouch! What a piece of auto-criticism for the lazy fellow you believe I am!).

The “paradise” to be reached (with its little angels, or its sausage-tree: it’s all the same) is the wrong way of posing the problem of man who does not feel he has the keys in his hands to allow him to fit in the world. Instead of looking for these keys, of learning to use them, he dreams of (or makes this the myth of his activity, wasting his time and labor) a world without locks, a non-world, a non-history, an “absolute human state.” Whereas the problem is precisely that of being aware of one’s own relativity, of becoming master of it, and knowing how to deal with this relativity.

Ever since I started reflecting on this, I notice that I’ve started classifying historical figures, writers, cultural movements into “paradisiacal” or not. As happens with these juxtapositions invented on the spot (which also have their own auxiliary usefulness, as long as one doesn’t dwell too long on them), the system always works out: the “paradisiacal” ones are all those that I systematically distrust, the “non-paradisiacal” are those from whom I believe I’ve gathered some “concrete teaching.”

How many paradises are there, for instance, in recent literature! What can be more “paradisiacal” than Surrealism? And psychoanalysis? And Gidean irresponsibility? But even more significant, it seems to me, is the fact that the most coveted myth in modern literature is the regressive paradise: memory. And what can one say about the gilded paradise of the Hermeticists: absence?

Behind this there always lies Romanticism, that great river of paradisiacal incontinence. And behind that again, Rousseau, the inventor of one of the most beloved ways of writing about paradise. (However, I believe we should go carefully with Rousseau’s myths: just because someone likes the South Seas—at a time when one could still believe in such things, of course—it is not necessarily the case that he has to be an unthinking escapist. If instead one goes there seriously, maybe one feels good there, and finds just what he wants: that’s what happened to Gaugin and Stevenson.)

And as far as I am concerned, “infernal” writers are also a subspecies of “paradisiacal” writers: they have the same preoccupation with some human absolute to be reached, which for them is the anti-human absolute, the terrifying God or his terrifying absence (or rather Absence). Kafka is the one who travels furthest in this infernal diretion, because he is the one who suffers it in concrete terms right to the end and wants to find out if there are really no ways out, and invents (or discovers as he looks around) certain Infernos that not even Dante would have dreamed up. (By the way, I don’t want to talk rubbish about Dante, but it seems to me that he is not “infernal” or “paradisiacal” at all, given that concern of his for men as they are, on the “earth.”) The French Existentialists instead are more inclined to act like children, to cultivate the inferno: the gelatinous, hairy inferno of “existing,” in Sartre; the cold insensate inferno, but with nearby beaches and parasols, in Camus.

I am certainly not looking to such people for examples of what I mean by “exit from paradise,” but to men who have as their homeland the things they do and see—a homeland that is constantly fraught with obstacles and has to be regained—these are “to the extent that” men, men who are impervious to marvelous hopes as much to marvelous despair.

On their side (I’ll continue to cite names of writers because they are more familiar to me; you might be able to replace them with names of philosophers since you know them better) there is Conrad, with his dark vision of the universe and his confidence in man, his morality which stems from the practicing of a skill, a job—working on sailing ships—(and this makes a rigid conservative of him, but who if not revolutionaries now learn from him?), his refusal to make a paradise of the tropics, the sea, which he sees as a test of man’s moral strength and technique. On their sides Chekhov, who gnaws pitilessly to the bone of every proud presumption of petit-bourgeois man (of human petit-bourgeois mentality), but he does so in order to discover beneath it, in each of us, that there is a man to be saved, in other words to test the historical utility of every man, which is—setting aside all the individual failures—the only human dignity and salvation. And as for the failures he recounts, what remains in your mind is the “positive” loophole that stays open despite everything, just as in his landscapes, in the loopholes of nature that he lets us glimpse every so often, you get a wonderful sense of breadth from the harmony of minute, scattered fragments. On their side is Hemingway—notwithstanding (or rather precisely because of) the fundamental American emptiness that he notices all around him and of which he too is a part—Hemingway who feels the need to go back to the basic relationships of man with things: fishing well, lighting fires well, establishing relations between a man and a woman well, and between men and other men, blowing up bridges well (except that he lacks the general perspective, and becomes futile and gets bored; what do bull-fights matter to us, even when well-done?).

I could go on, but I would like to point something out to you: I’ve provided the names of three atheists, and this is no accident. Actually these considerations can be expanded; that presupposition of a “paradise” (of the angelic or sausage variety), of man continually on the threshold of a kingdom that is his alone (and not belonging to him and the stone, say, or to him and the lizard, him and hydrogen, mold, whales, hail), that presupposition that the virtues that derive from things are separate from the things themselves, I now think I realize that this is what you call religion. Whereas this burying the rewards of one’s own actions in the furrow of one’s own duties and jobs, which have been established with science and confidence, would instead be the attitude toward the world that often in oral discussions with you I would uphold with the definition of atheistic atheism. You say that such a position cannot hold philosophically, but what does that matter? We have so many centuries ahead of us to think about it.

Only by going down this route, I believe, can one avoid “losing all real understanding of history,” “choosing a paradigm devoid of sense to evaluate it.”

Forgive me this garbled letter and for having chosen an (apparently) marginal topic to enter into discussion in your journal, but the mouse starts gnawing the cheese from the sides.

Italo Calvino

From Italo Calvino: Letters, 1941-1985. Princeton University Press. Edited by Martin McLaughlin. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2013. pp. 55-57.

FURTHER READING

The debate over the publication of Calvino’s letters to married actress Elsa de’ Giorgi.

Learning to Be Dead, an excerpt from Calvino’s 1983 novel Mr. Palomar.