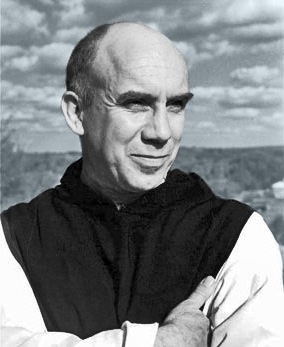

Below, American Catholic author Thomas Merton writes to Daniel J. Berrigan, who was in Prague at the time, establishing the Catholic Peace Fellowship. From there, Berrigan toured the Soviet Union before returning to New York City (by way of Africa) where he would become associate editor of Jesuit Missions. Merton had recently completed Seeds of Destruction which would be published that fall.

August 4, 1964

…When you come down in the fall, the purpose will be for you to give us a talk on South Africa, and also another one on anything else you like, religious life, aggiornamento, etc. Would you want to talk at Loretto? They are eager to have you.

I forget what news I have to give, if any. I don’t think it is much hotter in Africa than it is here. I have a book coming in the fall with a big chunk of peace stuff in it after all. That is nice. I look forward to seeing you and John H. and a few others in October but let’s make it purposeless and freewheeling and a vacation for all and let the Holy Spirit suggest anything that needs to be suggested. Let’s be Quakers and the heck with projects. I am so sick, fed up and ready to vomit with projects and hopes and expectations.

Let me write about this for a moment, even at the risk of being neurotic about it. It is of course not God’s will that a religious or a priest should spend his life more or less in frustration and defeat over the most important issues that face the Church. But you and I know that, in fact, that is what a lot of people have to face. I have a great deal less reason to complain of it than most. I have been extraordinarily fortunate in chances to speak, much much more than one would expect in a Trappist monastery of all places, so that really I have been blessed with special graces. So I should not complain. However, at the same time I realize that I am about at the end of some kind of a line. What line? What is the trolley I am probably getting off? The trolley is called a special kind of hope. The streetcar of expectation, of proximately to be fulfilled desire of betterment, of things becoming much more intelligible, of things being set in a new kind of order, and so on. Point one, things are not going to get better. Point two, things are going to get worse. I will not dwell on point two. Point three, I don’t need to be on the trolley car anyway, I don’t belong riding in a trolley. You can call the trolley anything you like, I have got off it. You can call the trolley a form of religious leprosy if you like. It is burning out. In a lot of sweat and pain if you like but it is burning out for real. The leprosy of that particular kind of temporal home, that special expectation that young monks have, that priests have. As a priest I am a burnt-out case, repeat, burnt-out case. So burnt out that the question of standing and so forth becomes irrelevant. I just continue to stand there where I was hit by the bullet. And I will continue to stand there, saying Mass. Not that Mass doesn’t mean a thousand times more. You know what I mean. But I have been shot dead and the situation is somehow different. I have no priestly ax to grind with anyone or about anything, monastic either. This has got a bit of burning out to do yet, though. The funny thing is that I will probably continue to write books. And word will go round about how they got this priest who was shot and they got him stuffed sitting up at a desk propped up with books and writing books, this book machine that was killed. I am waiting to fall over and it may take about ten more years of writing. When I fall over, it will be a big laugh because I wasn’t there at all.

I do not propose this as a paradigm for anything or anyone, it is just something that happened (or did not happen, verbs are deceptive) to me (pronouns are even more deceptive than verbs).

I am sick up to the teeth and beyond the teeth, up to the eyes and beyond the eyes, with all forms of projects and expectations and statements and programs and explanations of anything, especially explanations about where we are all going, because where we are all going is where we went a long time ago, over the falls. We are in a new river and we don’t know it.

With this spiritual nosegay I declare myself your happy and insouciant Kentucky friend, and nowonder Henry Miller says I look like an ex-con and like him and like Genet. Actually, though, it is only Picasso I look like which is deceptive: he got money.

From The Hidden Ground of Love: the Letters of Thomas Merton on Religious Experience and Social Concerns. Edited by William H. Shannon. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1985. pp. 83-4.

FURTHER READING

Read an essay by Merton on his Confessions of Crimes Against the State.

Read an article on Daniel Berrigan’s role in Occupy Wall Street at the age of 92.

Watch a PBS special on the life of Thomas Merton.