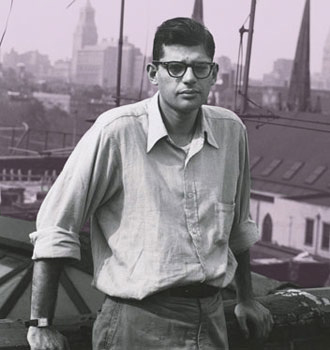

Below, Beat poet Allen Ginsberg addresses his close friend Jack Kerouac, whom he met while attending Columbia University. They wrote frequently to each other throughout their careers, a correspondence initially fueled by Ginsberg’s romantic attraction to Kerouac. Kerouac once told Lawrence Ferlinghetti (poet and co-founder of City Light Books): “Someday ‘The Letters of Allen Ginsberg to Jack Kerouac’ will make America cry.” At the time of this letter’s writing, Kerouac was looking for work and Ginsberg was enrolled at the Maritime Service Training Station in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn.

Paterson, New Jersey

Late July, 1945

Cher Breton:

I am sorry that we could not rescue a final meeting from our departure. The good Dr. Luria [a doctor with the Merchant Marine] told me you’d called, and I sent another postcard in haste. I’m writing a last time in the hope of reaching you before your voyage. A moi — Tomorrow morning, all the preliminaries have been dispensed with, I shall sign into the Merchant Marine, Incipit vita nuova! Monday I shall leave for Sheepshead Bay, where I hope to tutor myself anew in all these strange realities I have learned from the purgatorial season.

Your letter came to me after I returned from a fruitless journey into New York to recapture the grandeur of another time, and it came, almost, as a letter from the past, and conjured up in me all the emotions I had been seeking the days before.

But, Jack, rest assured that I shall return to Columbia. Bill [Burroughs] never advised me to stray from the fount of higher learning! I should return, however, to finish college, even if it were only a pilgrimage of acceptance of former time…

I understand, and I was moved that you were openly conscious that we were not the same comme amis. I have known it, and respected this change, in a way. But perhaps I should explain, for I have felt myself mostly responsible for it. We are of different kinds, as you have said, and I acknowledge it more fully now than before, because at one time I was fearful of this difference, perhaps ashamed of it. Jean, you are an American more completely than I, more fully a child of nature and all that is of the grace of the earth. You know, (I will digress) that is what I admired in him, our savage animal Lucien. He was the inheritor of nature; he was gifted by the earth with all the goodness of her form, physical and spiritual. His soul and body were consonant with each other, and mirrored each other. In much the same way, you are his brother. To categorize according to your own terms, though intermixed, you are romantic visionaries. Introspective yes, and eclectic, yes.

I am neither romantic nor a visionary, and that is my weakness and perhaps my power; at any rate it is one difference. In less romantic and visionary terms. I am a Jew, (with powers of introspection and eclecticism attendant, perhaps.) But I am alien to your natural grace, to the spirit which you would know as a participator in America. Lucien and yourself are much like Tadyis [the young, handsome boy in Death in Venice]; I am not so romantic or inaccurate as to call myself Aschenbach [the old professor who is infatuated with Tadyis], though isolate; I am not a cosmic exile such as [Thomas] Wolfe (or yourself) for I am an exile from myself as well. I respond to my home, my society as you do, with ennui and enervation. You cry “oh to be in some far city and feel the smothering pain of the unrecognized ego!” (Do you remember? We were self ultimate once.) But I do not wish to escape to myself, I wish to escape from myself. I wish to obliterate my consciousness and my knowledge of independent existence, my guilts, my secretiveness, what you would (perhaps unkindly) call my “hypocrisy.” I am no child of nature, I am ugly and imperfect to myself, and I cannot through poetry or romantic visions exalt myself to symbolic glory.

Lest you misunderstand me, I do not, or do not yet, own this difference to be an inferiority. I have sensed that you doubted my — artistic strength — shall we call it? Jean, I have sincerely long ceased to doubt my power as a creator or initiator in art. Of this I am sure. But even if I would, I cannot as you look on it as ultimate radiance, or saving glory, redeeming genius. Art has been for me, when I did not deceive myself, a meager compensation for what I desire. I am bored with these frantic cravings, tired of them and therefore myself, and contemptuous, though tolerant of all my vast powers of self-pity and self-expressive misery. What am I? What do I seek? Self-aggrandizement, as you describe it, is a superficial description of what my motives are, and my purposes. If I overreach myself for love, it is because I crave it so much, and have known so little of it. Love as perhaps an opiate; but I know it to be creative as well. More as a self-aggrandizement that transcends the self-effacement that I unconsciously strive for, and negates the power of self-aggrandizement. I don’t know if you can understand this. I renounce the pain of the “frustrated ego,” I renounce poetic passive hysteria; I have known them too long, and am worn and enervated from seeking them too successfully. I am sick of this damned life!

Well, these last years have been the nearest to fulfillment of my desires, and truthful feeling I thank you for the gift. You were right, I suppose, in keeping your distance, I was too intent on self-fulfillment, and rather crude about it, with all my harlequinade and conscious manipulation of your pity. I overtaxed my own patience and strength even more than I did yours, possibly. You behaved like a gentleman; though I think that you did take me too seriously, assign too much symbolic value to my motion and friction. There is much that was not merely ironic, but also purposeless and foolish in myself and my activity. I can’t forget Burroughs’ tolerant smiles as I mockingly and seriously explained to him all the devious ways of my intelligence. Still, Jack, I was conscious of all that I did, and inwardly sincere at all times, and this I have always been. I wonder if you comprehend the meanings which I can’t explain. Well, though in poetry I shall lie whitely and elevate these frustrations to “wounds,” I shall have flashes of insight and know better. At any rate, if you are able to understand me, I ask your tolerance; if not, I plead for your forgiveness. When we meet again I promise you that seven months will have elapsed profitably, that we will meet again as brothers in comedy, a tragedy, what you will, but brothers.

What is ahead I do not know; a valediction is our heritage; the season dies for a time, and until it is resurrected we must die as well. To all who perish, all who lose, farewell; to the stranger, to the traveler, to the exile, I bid farewell; to the penitents and judges of the trial, farewell; to the pensive and thunderous youth, farewell; to the gentle children and the sons of wrath, to those with flowers in their eyes, of sorrow or of sickness, a tender adieu.

Allen

From: Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg: The Letters. New York: Penguin Books, 2010.

FURTHER READING

Watch a Writer’s Guild Foundation interview with Kill Your Darlings screenwriter Austin Bunn and director John Krokidas.

Read The Rumpus’ essay on the 56th anniversary of Howl’s seizure by U.S. customs agents on grounds of obscenity, an anniversary occurring on the same day as the Supreme Court’s hearing of the cases regarding California Proposition 8 and the Defense of Marriage Act.

Read a New York Times piece about the founding of the core Beats friendships at Columbia University and view a map of key locations on the University campus.