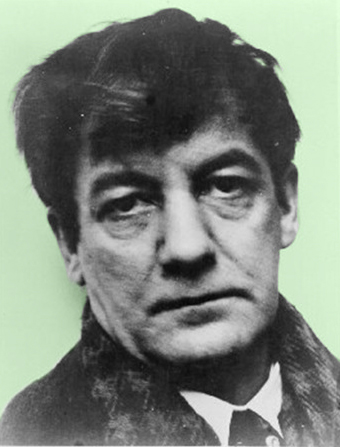

In the letter below, Sherwood Anderson writes to photographer Alfred Stieglitz, famous for his efforts to promote and support modern art as a patron, gallery owner, and collector. Stieglitz was married to Georgia O’Keeffe, of whom he produced more than 350 mounted prints. At the time of his writing, Sherwood Anderson was living in Reno, Nevada, where he had moved in order to facilitate his divorce from sculptor Tennessee Mitchell. Anderson dedicated his semi-autobiographical novel A Story Teller’s Story to Stieglitz, stating that he was “more than a father to so many puzzled, wistful children of the arts.”

Reno, June 30, 1923

Dear Alfred Stieglitz: Where will one find another such as you, to take the trouble to write me when you are so tired and distraught? I imagine these things begin to happen after a time, people on whom one had depended begin to disappear, the place begins to seem empty. But, dear man, you do so make the world a living place for so many people. I imagine only a few have really got to know you. It takes time and a kind of power in oneself to know another just as it does to get anywhere in one of the crafts. There are little distracting things not understood in oneself and the other. As for myself, I freely admit that I have often been stupid about you, and it was only last year that I came to know and really value you.

One day I was going to the country, and as I sat in the train, I suddenly began to weep bitterly and had to turn my face away from the people in the car for shame of my apparent[ly] causeless grief. However, I was not unhappy. It was just that I had at last realized fully what your life had come to mean to me. In our age, you know, there is much to distract from the faithful devotion to cleanliness and health in one’s attitude toward the crafts, and it takes time to realize what the quality has meant in you. I really think, and, you have registered more deeply than you know on Marin, O’Keeffe, Rosenfeld, myself and others. I myself was helped to an understand[ing] of you and your life by just a chance remark dropped by Marin. It illuminated and made clear a whole side of your nature I had not understood.

My new book Horses and Men is in press and, I hope, will turn out to be a real book of tales. There are some new ventures in it that have, I believe, real significance. In the meantime I get along into this semi autobiographical thing on which I am at work. It is thoughts, notions, and tales all thrown together. The central notion is that one’s fanciful life is of as much significance as one’s real flesh-and-blood life and that one cannot tell where the one cuts off and the other begins. This thing I have thought has as much physical existence as the stupid physical act I yesterday did. In fact, so strongly has the purely fanciful lived in me that I cannot tell after a time which of my acts had physical reality and which did not. It makes me in one sense a great liar, but, as I said in the Testament, “It is only by lying to the limit one can come at truth.”

I was a good deal disconcerted last year when I saw you in the Galleries doing a thing I thought might well kill you if you did not let up, and now I am glad enough to think of you up there at that quiet place with O’Keeffe. And whatever blows the actuality of life may deal you, I think you may well know that no other man of our day is so deeply loved. You have kept the old faith that gets so lost and faint, but that always has some man like yourself to make it real again to the younger ones. At any rate, you may know that this feeling I have come to have for you is no sudden thing, but a slow, sure growth.

It is dear of you to want me to have the things of your[s], and I want to have them. I get them out every day and look at them, and they are symbols to me of you and the real morality of you. They are living things to me, and I suppose that is what every artist wants—to leave thus living traces of the fine thing in himself for other craftsmen to see and understand a little.

Bless you, man. I hope the summer will bring peace and rest, and naturally I hope after a time you will begin working again, as of course you will.

Do you know the letter Petrarch wrote to Boccaccio when Boccaccio was foolish enough to write to Petrarch and suggest that he, Petrarch, was tired and had better not try to work any more? It is answer. My love to O’Keeffe. I have one little painting you and she may like a little—no more.

With love.

From The Letters of Sherwood Anderson. Edited by Howard Mumford Jones. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1953. pp. 99-100.

FURTHER READING

Read an essay by Anderson in praise of Stieglitz, first published in The New Republic.