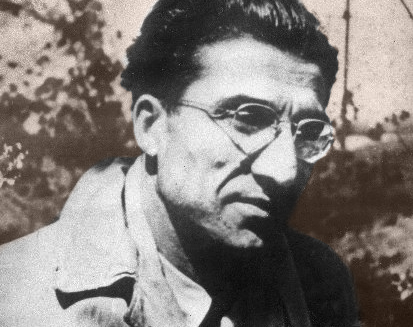

Cesare Pavese’s life often mirrored that of his protagonists: lonely and solitary.

To Enso Monferini, Ancona

Turin [January 1938]

Dear Enso,

I have often meant to answer your letter of last summer, but, as you know, pressure of work leaves me hardly time to breathe.

You gave me excellent advice, as far as it went. I should be sincere in everything I do and learn to accept responsibility. But you took no account of the influence of women or, rather, of one particular woman, on a man’s life. The very thought of it drove me to make a half-hearted attempt to gas myself.

How are you? And your new ‘friend’? Those happy days I spent at Ancona now seem incredibly remote. At that period I still had a shred of illusion and was deeply moved by the serenity of life in your home. I thought I could follow your example, but today I know I cannot. I still think enviously about your way of living. If a man’s misfortunes stem from his own ignorance and weakness, if he is by nature incapable and lacks any vestige of common sense, how can he escape his own destiny?

This isn’t a matter of moral sensibility. (As you know, I do not believe in any mystic divinity with supernatural powers). It’s a question of understanding, of coming to terms with life and managing to get along, the very art of living, and I’m convinced that unless a man has acquired these aptitudes by the time he is eighteen, he will never get them at all.

I beg you to believe that as I write this I am not blinded by passion. Day by day I reach a better understanding of myself, and I have come to the conclusion that, but for the education I absorbed involuntarily, which taught me to be afraid, I should have become a common cutthroat.

To think I was dreaming only of marrying her, working and being faithful to her! Good sense tell me: if it hadn’t been this girl, it would have been another. But I’m ready to swear that isn’t true, if only because of the knife-thrust she gave me when she said that sexually I could not satisfy a woman. It would be pointless and indecent to explain it to you, but I know it is true.

Please, please, do not spread this story when writing to friends, not even with the well-meaning intention of having me examined by a psychiatrist or someone of that sort. I have already done everything possible and have nothing to add.

In November I found a little peace by working like a dog on three translations at once, feeling like a starving man chewing paper. To you, happy in your own home with your little son, all this will seem like an ugly film-script, but to me it’s as real as a cancer.

When you reply to this letter, I should be grateful if you would refrain from making any reference to the matter. I’m writing to you as one would write an epilogue to a story, so as not to leave you in suspense, but I want no condolences, no sermons. I know how pointless they are.

Charity is useless, too, unless one has faith in God. ‘If there is no God, nothing is forbidden.’ Power is the only law. One can either live apart from the world (and how can that be possible, if it means remaining in the world?) or accept the rule of power. I’m a pessimist, too, this time seriously. If you can forget your home and children for a moment remember the conflagration of the ’14-18’ war, which destroyed not only humble people like me but a whole generation of intellectuals who opposed the rule of force. My dearest wish would have been to join them. In short, I live with the idea of suicide always in mind. That is far worse than having actually committed suicide, which, after all, is simply a sanitary operation.

How I wish I could live a little while with you, as I did last summer, chatting with Ernesto and roaming around with you. Though I’m convinced that all human intercourse falls short of one’s desire, I have terrible thirst for friendship and communal living, a longing shared by all elderly spinsters. You might well be my ideal friend, but I’m not threatening to visit you, if only because I have work to do.