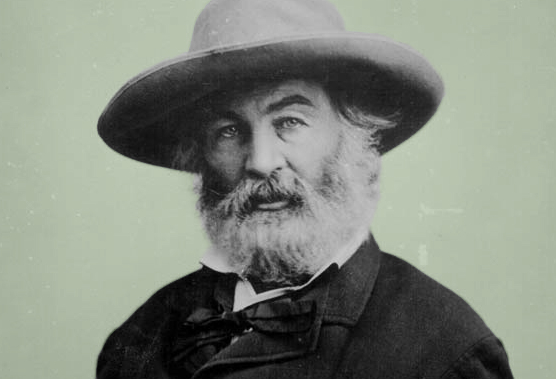

In this letter to his friend, the critic and editor William Michael Rosetti, Walt Whitman describes the Washington D.C. scenery before lamenting his work’s critical failure. Whitman was roundly criticized by the press, but, with the aid of Rosetti, gained a small, dedicated following in both Europe and the US. Rosetti edited a European edition of Leaves of Grass, eliminating any content that would offend British censors, and considered Walt Whitman to be “by far the greatest American poet.” A few years after this letter’s writing, Rosetti made great efforts to help Whitman out of poverty, raising the equivalent of $200,000 and requesting a government-sponsored poet’s pension from President Cleveland.

My dear Mr. Rossetti,

I send you my newest piece, (in a magazine lately started away off in Kansas, fifteen or eighteen hundred miles inland)—And also improve the occasion to write you a too-long-delayed letter. Your letters of July 9 last, & Oct. 8, were welcomed—since which last nothing from you has reached me. John Burroughs returned with glowing accounts of England, & heartiest satisfaction from his visits to you, & talks, &c. I saw him day before yesterday. He is well & flourishing.

I still remain here as clerk in a government department—find it not unpleasant—find it allows quite a free margin–working hours from 9 to 3—work at present easy—my pay $1600 a year (paper)—

Washington is a broad, magnificent place in its natural features—avenues, spaces, vistas, environing hills, rivers, &c. all so ample, plenteous—& then, as you go, on fine, hard wide roads, (made by military engineers, in the war) leading far away down dale & over hill, many & many a mile—Often of full-moonlight nights I have a habit of going on long jaunts with some companion six, eight miles away into Virginia or Maryland over these roads. It is wonderfully inspiriting, with such new presentations. We have spells here, night or day, of the finest weather & atmosphere in the world. The nights especially are at times miracles of clearness & purity—the air dry, exhilarating. In fact, night or day, this whole District affords an inexhaustible mine of explorations, walks—soothing, sane, open-air hours. To these mostly my habits are adjusted. I have good sturdy health—am fortunate enough to almost always get out of bed in the morning with a light heart & a good appetite—I read or study very little–spend two or three hours every day on the streets, or in frequented public spaces–come sufficiently in contact with all sorts of people—go not at all in “society” so-called–have however the blessing of some first-rate women friends—My life, upon the whole, toned down, flowing calm enough, democratic, on a cheap scale, popular, suitable, occupied sufficiently, enjoying a good deal–flecked, of course with some clouds & shadows. I still keep in good flesh & weight. The photos I sent you last fall are faithful of physiognomical likenesses. (I still have yours, carte, among a little special cluster before me on my desk door.)

My poetry remains yet, in substance, quite recognized here in the land for which it was written. The best-established magazines & literary authorities (eminencies) quite ignore me & it. It has to this day failed to find an American publisher (as you perhaps know, I have myself printed the successive editions). And though there is a small minority of approval and discipleship, the great majority result continues to bring sneers, contempt, & official coolness. My dismissal from moderate employment in 1865 by the Secretary of the Interior, Mr. Harlan, avowedly for the sole reason of my being the author of “Leaves of Grass,” still affords an indication of the high conventional feeling. The journals are often inveterately spiteful…

Of general matters here, I will only say that the country seems to have entirely recuperated from the war. Except in a part of the Southern States, every thing is teeming & busy—more so than ever. Productiveness, wealth, population, improvements, material activity, success, results—beyond all measure, all precedent—& then spreading over such an area—three to four millions square miles—Great debits and offsets, of course—but how grand this oceanic plenitude & ceaselessness of domestic comfort–universal supplies of eating and drinking, houses to live in, farms to till, copious travelling, migratory habits, plenty of money, extravagance even—true there is something meteoric about it, and yet from an overarching view it is Kosmic and real enough—It gives glow & enjoyment to me, being and moving amid the whirl & din, intensity, material success here—as I am myself sufficiently sluggish & ballasted to stand it–though the best is with reference to its foundation & for bearing on the future—(as best is with reference to its foundation for & bearing on the future—(as you doubtless see in my book how this though prevails with me).

…I shall be happy to receive a copy of your Selections from American Poets, when ready—& always, glad, my friend, to hear from you—hope, indeed, you will not punish me for my own delay—but write me fully & freely.

Walt Whitman

P.S. Will send the magazine by next mail.

From The Selected Letters of Walt Whitman. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press (1990).

FURTHER READING

Account of Rosetti’s love of Whitman’s work.

The Atlantic writes in 1882 on the poet’s mixed reputation.