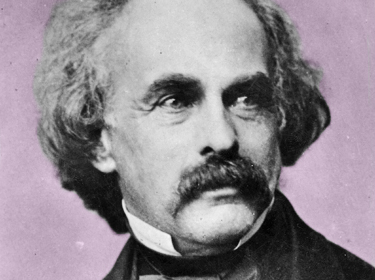

Sophia Peabody, transcendentalist philosopher and artist, is best known for her domestic role as wife to Nathaniel Hawthorne. An accomplished painter, she was far more independent and spirited than her husband’s biographers frequently acknowledge her to be. This is in part due to the way Hawthorne emphasizes her infirm health and ethereal appearance in his correspondences. His most frequently used trope, as exemplified in the letter below, is the image of the “naughty Dove” who flies away, only to return, reformed, in order to seek shelter in the breast pocket of her master’s coat. Although Hawthorne uses the terms of husband and wife in order to describe their relationship, the couple had not yet married.

Boston, October 3d, 1839. ½ past 7 P.M.

Ownest Dove;

Did you get home safe and sound, and with a quiet and happy heart? Providence acted lovingly toward us on Tuesday evening, allowing us to meet in the wide desert of this world, and mingle our spirits. It would have seemed all a vision then, now we have the symbol of its reality. You looked like a vision, beautifullest wife, with the width of the room between us—so spiritual that my human heart wanted to be assured that you had an earthly vesture on…

Do you remember a story of a cat who was changed into a lovely lady?—and on her bridal night, a mouse happened to run across the floor; and forthwith the cat-wife leaped out of bed to catch it. What if mine own Dove, in some woeful hour for her poor husband, should remember her dove-instincts,and spread her wings upon the western breeze, and return to him no more! Then would he stretch out his arms, poor wingless biped, not having the wherewithal to fly, and say aloud—“Come back, naughty Dove!—whither are you going?—come back, and fold your wings upon my heart again, or it will freeze!” And the Dove would flutter her wings, and pause a moment in the air, meditating whether or not she should come back: for in truth, as her conscience would tell her, this poor mortal had given her all he had to give—a resting-place on his bosom—a home in his deepest heart. But then she would say to herself—“my home is in the gladsome air—and if I need a resting-place, I can find one on any of the sunset-clouds. He is unreasonable to call me back; but if he can follow me, he may!“

Then would the poor deserted husband do his best to fly in pursuit of the faithless Dove; and for that purpose would ascend to the topmast of a salt-ship, and leap desperately into the air, and fall down head-foremost upon the deck, and break his neck. And there should be engraven on his tombstone—“Mate not thyself with a Dove, unless thou hast wings to fly.”

Now will my Dove scold at me for this foolish flight of fancy;—but the fact is, my goose quill flew away with me. I do think that I have gotten a bunch of quills from the silliest flock of geese on earth.

…Now, good night, truest Dove in the world. You will never fly away from me; and it is only the infinite impossibility of it that enables me to sport with the idea.

…Mine own Dove, I dreamed the queerest dreams last night, about being deserted, and all such nonsense…It seems to me that my dreams are generally about fantasies, and very seldom about what I really think and feel. You did not appear visibly in my last night’s dreams: but they were made up of desolation; and it was good to awake, and know that my spirit was forever and irrevocably linked with the soul of my truest and tenderest Dove. You have warmed my heart, mine own wife: and never again can I know what it is to be cold and desolate, save in dreams. You love me dearly—don’t you?

And so my Dove has been in great peril since we parted. No—I do not believe she was; it was only a shadow of peril, not a reality. My spirit cannot anticipate any harm to you, and I trust you to God with securest faith. I know not whether I could endure actually to see you in danger: but when I hear of any risk—as, for instance, when your steed seemed to be on the point of dashing you to pieces (but I do quake a little at that thought) against a tree—my mind does not seize upon it as if it had any substance. Believe me, dearest, the tree would have stood aside to let you pass, had there been no other means of salvation. Nevertheless, do not drive your steed against trees willfully.

Mercy on us, what a peril that was of the fat woman, when she “smashed herself down” beside my Dove! Poor Dove! Did you not feel as if an avalanche had all but buried you. I can see my Dove at this moment, my slender, little delicatest white Dove, squeezed almost out of Christendom by that great mass of female flesh—that ton of woman—that beef-eater and beer-guzzler, whose immense cloak, though broad as a ship’s mainsail, could not be made to meet in front—that picture of an ale-wife—that triple, quadruple, dozen-fold old lady.

Will not my Dove confess that there is a little nonsense in this epistle? But be not worth with me, darling wife;—my heart sports with you because it loves you…

Your Ownest Husband.

FURTHER READING

An extensive discussion of Hawthorne’s use of the rhetorical “dove” can be found in the biography Sophia Peabody, A Life, by Patricia Dunlavy Valenti (University of Missouri Press, 2004).

For general information on Hawthorne family life, read here.