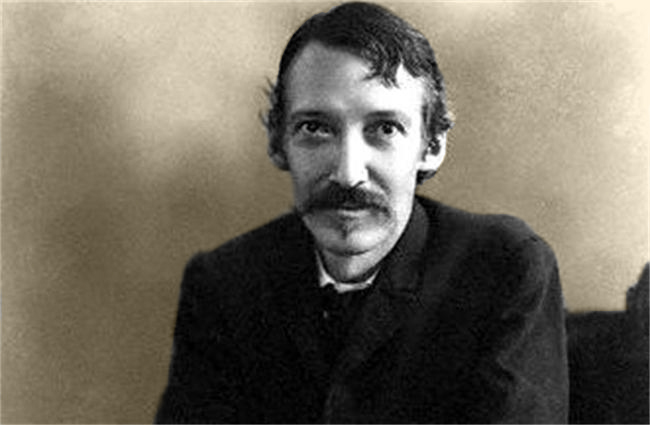

In the following letter, Robert Louis Stevenson addresses his close friend (and scandalous woman of society) Mrs. Fanny Sitwell. Sitwell, separated from her minister husband, struck up an intimate friendship with a number of male acquaintances, and formed a particularly close relationship with Stevenson. The two corresponded frequently. Despite the talk of other women in the letter, Stevenson’s intentions were romantic; Sitwell, twelve years his elder, served as the departure for many of his romantic fantasies.

November 28, 1874

Edinburgh

To Mrs. Sitwell:

Well, I’ve got some women now, and they’re better than nothing…I have come now to think the sitting figure, in spite of its beautiful drapery rather a blemish, rather an interruption to the sentiment. [They] are better than one has ever dreamed; I think these two women are the only things in the world that have been better than, in Bible phrase, it had entered into my heart to conceive. Was it Pheidias? Or do they not know? It is wonderful they are—noble company. And then I have now three Japanese pictures that are after my own heart, and I get up from time and turn a bit of favourite colour over and over, roll it under my tongue, savour it till it gets all through me; and then back to my chair and to work.

This afternoon about six there was a small orange moon, lost in a great world of blue evening. A few leafless boughs, and a bit of garden railing, criss-cross its face; and below it there was blueness and the spread lights of Leith, lost in blue haze. To the east, the town, also subdued to the same blue, piled itself up, with here and there a lit window, until it could print off its outline against a faint patch of green and russet that remained behind the sunset.

…I cannot write English because I have been speaking French all evening with some French people of my knowledge. It’s a sad thing, the state I get into, when I cannot remember English and yet do not know French! And it is worse when it is complicated, as at present, with a pen that will not write! If you knew how I have to paint and how I have to manoeuvre [sic] to get the stuff legible at all.

…I have said the Fates are only women after a fashion; and that is one of the strangest things about them. They are wonderfully womanly—they are more womanly than any woman—and those girt draperies are drawn over a wonderful greatness of body instinct with sex; I do not see a line in them that could be a line in a man. And yet, when all is said, they are not women for us; they are of another race, immortal, separate; one has no wish to look at them with love, only with a sort of lowly adoration, physical, but wanting what is the soul of all love, whether admitted to oneself or not, hope; in a word ‘the desire of the moth for the star.’ O great white stars of eternal marble, O shapely, colossal women, and yet not women. It is not love that we seek from them, we do not desire to see their great eyes troubled with our passions, or the great impassive members contorted by any hope or pain or pleasure; only now and again, to be conscious that they exist, to have knowledge of them far off in cloudland or feel their steady eyes shining, like quite watchful stars, above the turmoil of the earth

…if all goes to the worst, shall I not be able to lay my head on the great knees of the middle Fate—O these great knees—I know all Baudelaire meant now with his géante—to lay my head on her great knees and go to sleep.

…I know now that there is a more subtle and dangerous sort of selfishness in habit than there ever can be in disorder. I never ceased to be generous when I was most déréglé; now when I am beginning to settle into habits, I see the danger in front of me—one might cease to be generous and grow hard and sordid in time trouble. However, thank God it is life I want, and nothing posthumous, and for two good emotions I would sacrifice a thousand years of fame. Moreover I know so well that I shall never be much as a writer that I am not very sorely tempted…My only chance is in my stories…

From The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson. Ed. By Sidney Colvin. New York: Scribner (1911).

FURTHER READING

The metaphor of the moth seeking the moon can be found in Percy Shelley’s homage to a lover, “One Word is Too Often Profaned.”

For a description of the mammoth-sized female, see Baudelaire’s poem “The Giantess.”

Look here for an extensive Stevenson biography.