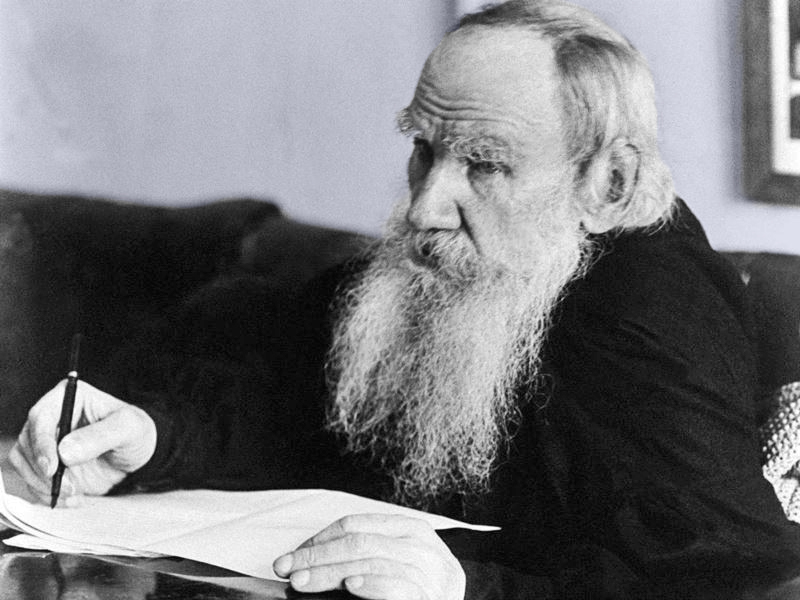

Below, Tolstoy writes to Vladimir Chertkov, who he had met in 1883. Together they founded The Intermediary in 1884, a publishing house for a popular audience which facilitated the dissemination of Tolstoy’s writings. After Tolstoy’s death, Chertkov was nominated to the position of editor-in-chief for the memorial edition of the author’s works. Below, Tolstoy mentions notable guests at his home, Yasnaya Polyana. Among them was Mikhail Sosnovsky, a member of the revolutionary terrorist organisation “The People’s Will,” who would be arrested one year later for his ties to an assassination attempt on Alexander III.

Yasnaya Polyana, 28 May 1886

I got your letter, dear friend, and was very glad of it. Mine, I suppose, won’t find you in Petersburg. We are well here. I continue to work a little—more with my hands now than with my head, since I’m more attracted to that sort of work. Besides, there have been many guests. We have had Ozmidov, Gribovsky and Marya Alexandrovna Schmidt, and Sosnovsky is here now. I was very glad to see Ozmidov. And I got on very well with him. I’m also glad that the prejudice against him in my family has been overcome. Gribovsky is very young. This is the main thing to remember about him, as well as the fact that the first awakening of his spiritual activity was revolutionary—scientific, as it’s called. What a terrible plague this is! The same is true to a far greater degree with Sosnovsky. We often delude ourselves by thinking that when we meet revolutionaries, we stand close by their side. No state—no state; no property—no property; no inequality—no inequality; and much else. It seems we’re just the same. But not only is there a big difference; there are no people further apart from us. For a Christian there is no state, but for them it is necessary to destroy the state; for a Christian there is no property, but they destroy property. It’s just like two ends of a ring that hasn’t been joined up. The ends are adjacent, but they are further apart from each other than all the other parts of the ring are. You have to go right round the ring in order to join up the ends.

Sosnovsky and Feinermann interrupted me as I was writing this letter. They came from the country (Sosnovsky had spent 2 days with Feinermann) and we had a very good talk. Incidentally I read to Sosnovsky what I’m writing about him. I liked him very much. There’s a lot of goodness in him. He’s just leaving now. If you have copied out the beginning of the story about the peasant and the boy (from my papers: it’s in a very messy state), send it to me. I was thinking about it today. Perhaps I shall manage to finish it. I’m busy now not only with the Buddha, but with Brahmanism, Confucius and Lao-Tzu. Perhaps nothing will come of it, but perhaps something will—which I won’t write about because you can’t say anything in a letter. There are heaps of guests here today—young people, Seryozha, Kuzminsky—inundating us with frivolities and temptations for the children, and the children succumb, while I struggle, not against temptations, but against anger at those who introduce them. I hope God will help. At moments like this I think with special affection about you and all who are near to me. Write more often, dear friend. Give regards to your mother. Sosnovsky asked me to send his warm regards. All my family remember you with love.

From Tolstoy’s Letters Volume II: 1880-1910. Edited and translated by R. F. Christian. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1978.

FURTHER READING

View a series of photographs of Tolstoy and Chertkov.

Learn about Tolstoy and Chertkov’s first meeting.