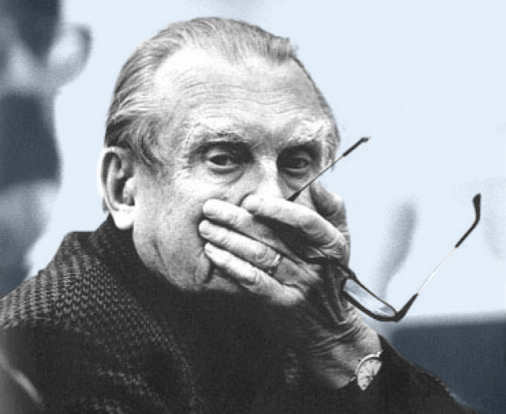

Czesław Miłosz writes to Thomas Merton, forming one link in the long chain of correspondence between the worldly poet and the Trappist monk. Miłosz diagnoses the malaise of modernity as a problem of dualist perception, and offers Merton advice on how to make his literary work more accessible and appealing to non-Catholic readers.

28.II.60

Dear Merton,

Centuries. Once I wrote a long letter to you but did not send it. First, about your books. You forgive me if I approach them now from a practical angle instead of writing essays of criticism. Since I believe I cannot yeah higher than “active contemplation” as you call it in your reappraisal; the practical aspect is for me important. I wish your books had influence not only upon Roman Catholics. If I cling to such people as you, in spite of my weak faith, it is because I am revolted against that complete craziness one observes today in art and literature and which reflects a more general madness. Of late I saw Les Nègres of Jean Genet, already typical by its diabolical skill put to the use of “ricanement.” That play opens and ends by a celestial Mozart music just to make the audience better taste two hours of blasphemies and hatred in the middle. Perhaps we approach a time when only groups of monks in monasteries will remain sane. Your books should have influence. Yet I see an obstacle. To put it briefly (too briefly) it is your kind of sensitivity, reinforced probably by your training. Let us take the example of your diary. Every time you speak of Nature, it appears to you as soothing, rich in symbols, as a veil or curtain. You do not pay much attention to torture or suffering in Nature. You are completely right when you praise Boris Pasternak for his feeling of wholeness, of participation in the mystery of being. But he is so near to you just because of what is for you a danger as it can reduce your influence upon non-Catholics. We live through a time when Manichaeism is particularly strong and one could enumerate many reasons for it—though we do not grasp as yet all the causes. I do not know to what extent a sort of despair at the sight of ruthless necessity in Nature is justified. Yet it exists while it was not known until quite modern times. The distance between man and the rest of Creation was so great that for Descartes too the animal was a machine. Some old Manichaean elements started to revive perhaps in the Reformation but they were mitigated. You can say that overstressed compassion for millions and billions of creatures crushed every second makes part of the modern schism with destroyed quite real barriers between man and animal. But the bitter taste of necessity colors the style of our contemporaries and if Simone Weil is such a force and if she counterbalances many modern follies, it is because she was one Cathare. Albert Camus called her (in a letter) “the only great spirit of our time” and Camus undoubtedly was a Manichaean. By the way, I would like to convince you to comment upon La Chute de Camus, a very ambiguous book, which is a cry of despair and a treatise on Grace (absent). Perhaps it would be useful if you write a theological commentary. I am far from wishing to convert you to Manichaeism. Only it is so that the palate of your readers is used to very strong sauces and le Prince de ce monde is a constant subject in their reflections. That ruler of Nature and of History (if laws are different, necessity is similar) does not annoy you enough—in your writings. […]

I do not know how one should finish letters to you, there is this respect for the priest’s robe, let me say with brotherly love,

Czesław Miłosz