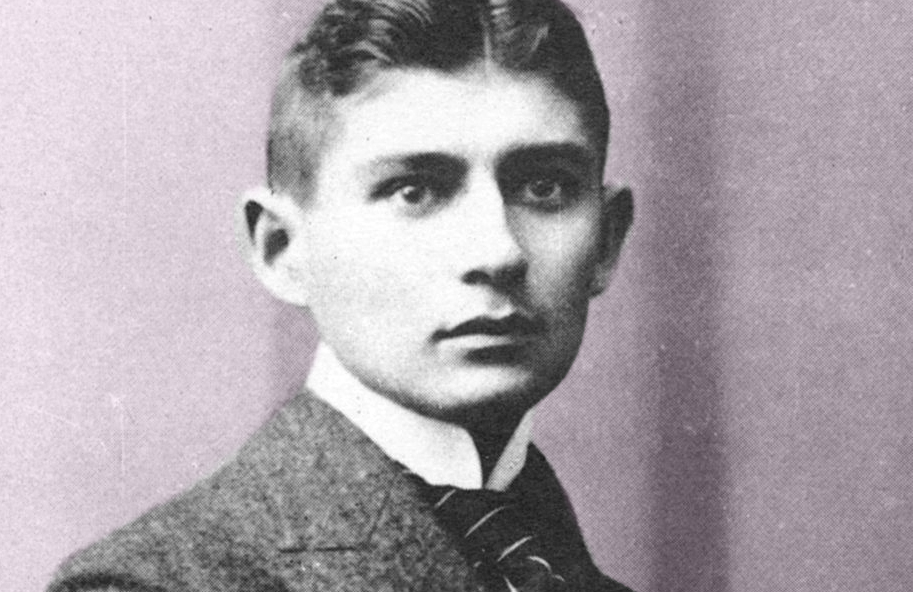

Writing to his close friend Max Brod, then a university classmate who would later become his biographer and literary executor, twenty-one-year-old Franz Kafka muses on the end of summer and the passage of time.

[Prague]

August 28 [1904]

It is so easy to be cheerful at the beginning of the summer. One has a lively heart, a reasonably brisk gait, and can face the future with a certain hope. One expects something out of the Arabian Nights, while disclaiming any such hope with a comic bow and bumbling speech—an exciting game that makes one feel cosy and all aquiver. One sits in one’s tossed bedding and looks at the clock. It reads late morning. But we paint the evening with subdued colors and distant views that stretch on and on. And we rub our hands red with delight because our shadow grows long and so handsomely crepuscular. We adorn ourselves, secretly hoping that adornment will become our nature. And when people ask us about the life we intend to live, we form the habit, in spring, of answering with an expansive wave of the hand, which goes limp after a while, as if to say that it was ridiculously unnecessary to conjure up sure things.

If we were to be totally disappointed, that would be sad, of course, but then again it would be the fulfillment of our daily prayer that the consistency of our life may be preserved, as far as external appearances go.

But we are not disappointed; this season which has only an end but no beginning puts us into a state so alien and natural that it could be the death of us.

We are literally carried by a vagrant breeze wherever it pleases, and there is a certain whimsicality to the way we clap our hands to our brows in the breeze, or try to reassure ourselves by spoken words, thin fingertips pressed to our knees. Whereas we are usually polite enough not to want to know anything about any insight into ourselves, we now weaken to some extent and go seeking it, although in the same manner as when we pretend to be trying hard to catch up with little children who are toddling slowly in front of us. We burrow through ourselves like a mole and emerge blackened and velvet-haired from our sandy underground vaults, our poor little red feet stretched out for tender pity.

On a walk my dog came upon a mole that was trying to cross the road. The dog repeatedly jumped at it and then let it go again, for he is still young and timid. At first I was amused, and enjoyed watching the mole’s agitation; it kept desperately and vainly looking for a hole in the hard ground. But suddenly when the dog again struck it a blow with its paw, it cried out. Ks, ks, it cried. And then I felt—no, I didn’t feel anything. I merely thought I did, because that day my head started to droop so badly that in the evening I noticed my chin had grown into my chest. But next day I was holding my head nice and high again. Next day a girl put on a white dress and fell in love with me. She was very unhappy over it and I did not manage to comfort her; you know how hard it is to do that. On another day when I opened my eyes after a short afternoon nap, still not quite certain I was alive, I heard my mother calling down from the balcony in a natural tone: “What are you up to?” A woman answered from the garden: “I’m having my teatime in the garden.” I was amazed at the stalwart technique for living some people have. Another day I exulted painfully in the drama of overcast weather. Then a week or two or even more whisked away. Then I fell in love with a woman. Then once there was dancing in the tavern and I didn’t go. Then I was down in the dumps and very stupid, so that I stumbled on the country roads, which are very steep around here. Then once I read this passage in Byron’s diaries (I am only paraphrasing because the book is already packed up): “For a week I have not left my house. For three days I have been boxing four hours daily with a boxing master in the library, with the windows open, to calm my mind.” And then, and then the summer was over and I find it is getting cool, getting to be time to answer the summer letters, that my pen has skidded a little and I might as well lay it down.

Yours, Franz K.

From Franz Kafka: Letters to Friends, Family, & Editors. Translated by Richard and Clara Winston. New York: Schocken Books, 1977. 509 pp.

FURTHER READING

To explore Kafka’s Wound, a digital literary essay by Will Self, click here.

Kafka retained the interest in moles he seems to exhibit here; his unfinished short story The Burrow describes the experience of a mole-like creature as it tunnels through its “sandy underground vaults.” Read one scholar’s analysis here.