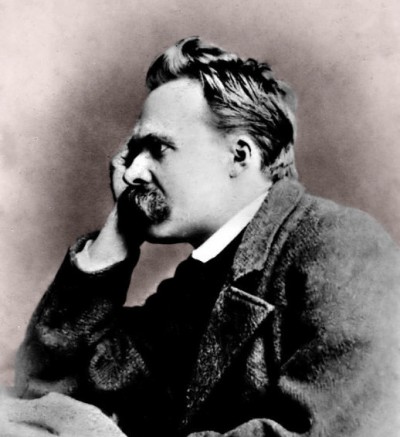

Below, Nietzsche pens an energetic—and, perhaps, uncharacteristically mirthful—dispatch to his mother, Franziska Oehler. The letter was, in part, compensatory, as Nietzsche himself was supposed to arrive at his mother’s at roughly this time. Of this incident, Nietzsche’s sister noted: “The touching letter from our dear mother is still extant in which she expresses her disappointment over the fact that after she had made all sorts of preparations, a letter came instead of her son.” Nietzsche had published his first work, The Birth of Tragedy, earlier this same year.

October, 1872

Spülgen, Hotel Bodenhaus

MY DARLING MOTHER:

This time you are going to laugh, for this long letter is all about a journey and lots of funny things. Half against my will I decided to go to Italy; though it lay heavily on my conscience that I had already written you a letter accepting. But who can resist the capricious manner in which the weather has suddenly become the reverse of what it was! Now it is beautifully and purely autumnal, just the very weather for a walking tour. Or, to be nearer the truth, I felt the most burning desire for once to be quite alone with my thoughts for a little while. You can guess from the address of the hotel printed above that I have been unexpectedly successful.

…I had almost reached Zurich when I discovered that my companion in the compartment was a man who was well known to me and had been even better recommended the musician Goetz (a pupil of Bülow’s) and he told me how much his musical work had increased in Zurich since Kirclmer’s departure. But what seemed to agitate him most of all was the prospect of seeing his opera accepted by the Hanover Theatre and produced for the first time. After leaving Zurich, in spite of the nice unobtrusive company, I gradually grew so cold and ill that I had not the courage to go as far as Chur. With great difficulty—that is to say, with a splitting headache—I reached Weesen and the Lake of Wallenstatt in the dead of night. I found the Schwert Hotel ‘bus and got into it, and it set me down at a fine, comfortable, though completely empty, hotel. On the following morning I rose with a headache. My window looked on to the Lake of Wallenstatt, which you can imagine as being like the Lake of Lucerne, but much simpler and not so sublime. Then I went on to Chur, feeling unfortunately ever more and more ill at ease—so much so that I went through Ragaz, etc., almost without feeling the slightest interest. I was very glad to be able to leave the train at Chur, refused the post officials offer to drive with him—which after all was the plan—and, putting up at the Hotel Lukmanier, I went straight to bed. It was 10 a.m. I slept well until 2 p.m., felt better and ate a little. A smart and well-informed waiter recommended me to walk as far as Pessug, a place that was imprinted on my memory by a picture I had seen of it in an illustrated paper. Sabbath peace and an afternoon mood prevailed in the town of Chur. I walked up the main road at a leisurely pace; as on the previous day, everything lay before me transfigured by the glow of autumn. The scenery behind me was magnificent, while the view constantly changed and widened. After about half an hours walk I came to a little side path which was beautifully shaded; until then the road had been rather hot. Then I reached the gorge through which the Rabiusa pours; its beauty defies description. I pressed on over bridges and paths winding round the side of the rock for about half an hour, and at last discovered Bad Passug indicated by a flag. At first it disappointed me, for I had expected a Pension and saw only a second-rate inn, full of Sunday excursionists from Chur—a crowd of comfortably feasting and coffee-sipping families. The first thing I did was to drink three glassfuls of the saline-soda spring; then the improved state of my head soon allowed me to add a bottle of white Asti Spumante—you remember it!—together with the softest of goat s milk cheese. A man with Chinese eyes, who sat at my table, also had some of the Asti to drink; he thanked me, drank and was much gratified. Then the proprietess handed me a number of analyses of the water, etc. Finally, Sprecher, the proprietor of the watering place, an excitable sort of man, showed me all over his property, the incredibly fantastic position of which I was obliged to acknowledge. Again I drank copious draughts of water from three entirely different springs. The proprietor promised the opening of important new springs, and noticing my interest in the matter offered to make me his partner in the founding of a hotel, etc., etc.—irony! The valley is extremely fascinating for a geologist of unfathomable versatility—aye, and even whimsicality. There are seams of graphite and there is also quartz with ochre. The proprietor even hinted at gold. You can see the most different kinds of stone strata and varieties of stone, bending hither and thither and cracked as in the Axenstein on the Lake of Lucerne, but here they are much smaller and less rugged. Late in the evening, just as it was getting dusk, I returned delighted with my afternoon, although my mind often wandered back to the reception I ought to have been enjoying at Naumburg. A little child with flaxen hair was looking about for nuts, and was very amusing. At last an aged couple came towards me, father and daughter. They had a few words to say, and listened in turn. He was a very old, hoary cabinet maker, had been in Naumburg fifty-two years ago while on his wanderings, and remembered a very hot day there. His son has been a missionary in India since 1858, and is expected to come to Chur next year in order to see his father once more. The daughter said she had often been to Egypt, and spoke of Bale as an unpleasant, hot, and stuffy town. I accompanied the good old hobbling couple a little further. Then I returned to dinner at my hotel, where I found one or two companions ready for the Splügen tour on the morrow. On Monday I rose at 4 a. in., the diligence being timed to leave just after 5. Before we left we had to sit in an evil-smelling waiting room, among a number of peasants from Graubünden and Tessin. But at this early hour man is in any case a disagreeable creature. I was released by the departure of the diligence, for I had arranged with the conductor to occupy his seat high up on the top of the conveyance. There I alone, and it was the finest diligence drive I have ever had. I cannot write about the tremendous grandeur of the Via mala; it made me feel as if I did not yet know Switzerland at all. This is my Nature, and when we got near to Splügen I was overcome by the wish to stay there. I found a good hotel and a little room that was quite touching in its simplicity. And yet it has a balcony from which one can enjoy a most beautiful view. This high Alpine valley (about 5,000 feet) is exactly to my taste pure and bracing air, hills and rocks of every shape and size, and mighty snow mountains all around. But what I like most of all are the magnificent high roads along which I walk for hours at a time, sometimes in the direction of Bernadino and sometimes along the heights of the Pass of Spülgen, without heeding the road in the least. But as often as I look about me I am certain to see something gorgeous and unexpected. To-morrow it is almost sure to snow, and I am heartily looking forward to it. In the afternoon, if the diligence arrives, I take my meal with the new arrivals. There is no need for me to speak to anyone; no one knows me; I am absolutely alone and could stay here for weeks, sitting and walking about. In my little room I work with renewed vigour that is to say, I make notes and collect ideas for the theme that is chiefly occupying me at present: “The Future of Our Educational Institutions.”

You do not know how pleased I am with this place. Since I have come to know it, Switzerland has acquired quite a new charm for me. Now I know of a nook where I can gain strength, work with fresh energy, and live without any company. In this place human beings seem to be like phantoms. Now I have described everything to you. The days that follow will all be like the first. Thank God, those damnations known as “change” and “distraction” are lacking here. Here I am together with my pen, ink, and paper. All of us send our heartiest wishes.

Your devoted son,

FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE.