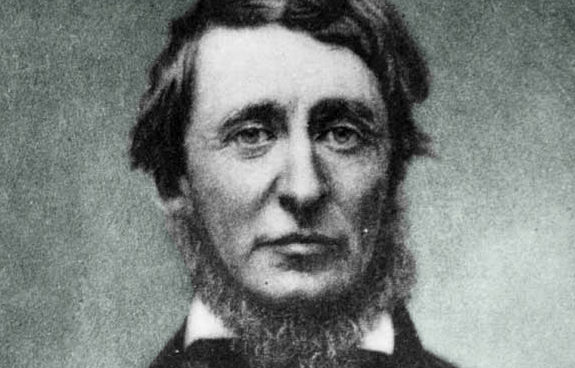

At the time of this letter’s writing, Henry David Thoreau had completed his experiment in simple living at Walden Pond. Yet, though he filled volumes of journals, he was better known as a pencil maker and evader of taxes than an author. He started delivering lectures in 1848 at the Concord Lyceum (on his brief stint in prison) and published his first essay, “Ktaadn,” about a hiking trip in Maine later that year. Below, Thoreau addresses Harrison Blake, an ex-Unitarian minister and widower from Worcester, Massachusetts. Blake first wrote to Thoreau after reading a transcription of one of his lectures, appearing to ask for spiritual council. This is Thoreau’s reply. The two became close correspondents, and upon Thoreau’s death in 1862, Blake took on the editing of Thoreau’s posthumous publications.

To Harrison Blake

March 27, 1848

Concord, Massachusetts

I am glad to hear that any words of mine, though spoken so long ago that I can hardly claim identity with their author, have reached you. It gives me pleasure, because I have therefore reason to suppose that I have uttered what concerns men, and that it is not in vain that man speaks to man. This is the value of literature. Yet those days are so distant, in every sense, that I have had to look at that page again, to learn what was the tenor of my thoughts then. I should value that article, however, if only because it was the occasion of your letter.

I do believe that the outward and the inward life correspond; that if any should succeed to live a higher life, others would not know of it; that difference and distance are one. To set about living a true life is to go [on] a journey to a distant country, gradually to find ourselves surrounded by new scenes and men; and as long as the old are around me, I know that I am not in any true sense living a new or a better life. The outward is only the outside of that which is within. Men are not concealed under habits, but are revealed by them; they are their true clothes. I care not how curious a reason they may give for their abiding by them. Circumstances are not rigid and unyielding, but our habits are rigid…

Change is change. No new life occupies the old bodies; —they decay. It is born, and grows, and flourishes. Men very pathetically inform the old, accept and war it. Why put it up with the almshouse when you may go to heaven? It is embalming, —no more. Let alone your ointments and your linen swathes, and go into an infant’s body. You see in the catacombs of Egypt the result of that experiment, —that is the end of it.

I do believe in simplicity. It is astonishing as well as sad, how many trivial affairs even the wisest man thinks he must attend to in a day; how singular an affair he thinks he must omit. When the mathematician would solve a difficult problem, he first frees the equation all encumbrances, and reduces it to its simplest terms. So simplify the problem of life, distinguish the necessary and the real. Probe the earth to see where your main roots run. I would stand upon facts. Why not see, —use our eyes? Do men know nothing? I know many men who, in common things, are not to be deceived; who trust no moonshine; who count their money correctly, and know how to invest it; who are said to be prudent and knowing, who yet will stand at a desk the greater part of their lives, as cashiers in banks, and glimmer and rust and finally go out there. If they know anything, what under the sun do they do that for? Do they know what bread is? Or what it is for? Do they know what life is? If they knew something, the places which know them now would know them no more forever…

Men cannot conceive of a state of things so fair that it cannot be realized. Can any man honestly consult his experience and say that it is so? Have we any facts to appeal to when we say that our dreams are premature? Did you ever hear of a man who had striven all his life faithfully and singly toward an object and in no measure obtained it? If a man constantly aspires, is he not elevated? Did ever a man try heroism, magnanimity, truth, sincerity, and find that there was no advantage in them? that it was a vain endeavor? Of course we do not expect that our paradise will be a garden. We know not what we ask. To look at literature;—how many fine thoughts has ever man had! how few fine thoughts are expressed! Yet we never have a fantasy so subtle and ethereal, but that talent merely, with more resolution and faithful persistency, after a thousand failures, might fix and engrave it in distinct and enduring words, and we should see that our dreams are the solidest facts that we know. But I speak not of dreams.

What can be expressed in words can be expressed in life.

My actual life is a fact in view of which I have no occasion to congratulate myself, but for my faith and aspiration I have respect. It is from these that I speak. Every man’s position is in fact too simple to be described. I have sworn no oath. I have no designs on society—or nature—or God. I am simply what I am, or I begin to be that…I love to live, I love reform better than its modes…I believe something, and there is nothing else but that. I know that I am…

As for positions—as for combinations and details—what are they? In clear weather when we look into the heavens, what do we see, but the sky and the sun?

…Men will believe what they see. Let them see.

Pursue, keep up with, circle round and round your life as a dog does his master’s chaise. Do what you love. Know your own bone; gnaw at it, bury it, unearth it, and gnaw it still. Do not be too moral. You may cheat yourself out of much life so. Aim above morality. Be not simply good—be good for something. —All fables indeed have their morals, but the innocent enjoy the story.

Let nothing come between you and the light. Respect men as brothers only. When you travel to the celestial city, carry no letter of introduction. When you knock ask to see God—none of the servants. In what concerns you much do not think that you have companions—know that you are alone in the world.

This I write at random. I need to see you, and I trust I shall, to correct my mistakes. Perhaps you have some oracles for me.

Henry Thoreau

FURTHER READING

“I fear not spirits, ghosts, of which I am one . . . but I fear bodies”: Joyce Carol Oates on Thoreau’s mysteries.

“Ktaadn,” at the Thoreau Reader.

The often overlooked correspondence between Thoreau and Blake, an outlet which allowed Thoreau to develop many of his ideas for Walden.

Walden in the digital age.