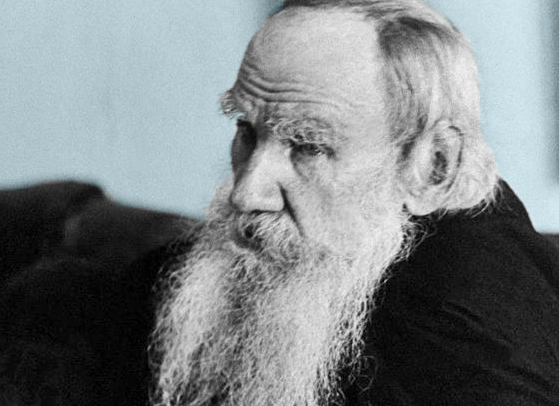

Leo Tolstoy responds to philosopher and critic Nikolai Strakhov’s reaction to Anna Karenina, and describes his vision for what literary criticism should be.

Yasnaya Polyana

[26 April, 1876]

Our letters to each other have crossed, dear Nikolai Nikolaievich. I have just replied to your philosophical letter when I got your heartening reply to mine. You write: do you understand my novel correctly, and what do I think about your opinions? Of course you understand it correctly. Of course your understanding heartens me beyond words; but not everyone is bound to understand it as you do. Perhaps you are only an amateur at these things, just as I am. Just like one of our Tula pigeon-fanciers. He rates a tumbler-pigeon very highly, but whether the pigeon has any real merits is another question. Besides, the likes of us, as you know, are constantly leaping without any transition from despondency and self-abasement to inordinate pride. I say this because your opinion about my novel is true, but isn’t everything—i.e. everything is true, but what you said doesn’t express everything I wanted to say. For example, you speak about two sorts of people. I always feel this—I know—but I didn’t intend it so. But when you say it, I know that it’s one of the truths which can be said. But if I were to try to say in words everything that I intended to express in my novel, I would have to write the same novel I wrote from the beginning. And if short-sighted critics think that I only wanted to describe the things that I like, what Oblonsky has for dinner or what Karenina’s shoulders are like, they are mistaken. In everything, or nearly everything I have written, I have been guided by the need to gather together ideas which for the purpose of self-expression were interconnected; but every idea expressed separately in words loses its meaning and is terribly impoverished when taken by itself out of the connection in which it occurs. The connection itself is made up, I think, not by the idea, but by something else, and it is impossible to express the basis of this connection directly in words. It can only be expressed indirectly—by words describing characters, actions and situations.

You know all this better than I do, but it has been occupying my attention recently. For me, one of the most manifest proofs of this was Vronsky’s suicide which you liked. This had never been so clear to me before. The chapter about how Vronsky accepted his role after meeting the husband had been written by me a long time ago. I began to correct it, and quite unexpectedly for me, but unmistakably, Vronsky went and shot himself. And now it turns out that this was organically necessary for what comes afterwards.

That’s why such a nice clever man as Grigoryev interests me very little. It’s true that if there were no criticism at all, then Grigoryev and you who understand art would be redundant. But now indeed when 9/10 of everything printed is criticism, people are needed for the criticism of art who can show the pointlessness of looking for ideas in a work of art and can steadfastly guide readers through that endless labyrinth of connections which is the essence of art, and towards those laws that serve as the basis for those connections.

And if critics already understand and can express in a newspaper article what I wanted to say, I congratulate them and can boldly assure them qu’ils en savent plus long que moi.

I’m very grateful to you. When I read through my last dejected and humble letter, I realized that I was really asking for praise and that you had send it to me. And your praise—sincere, I know, although, I’m afraid, too partial—is very, very, dear to me.

I’m very annoyed that I made mistakes over the wedding, as I love that chapter.

I’m afraid there may also be mistakes over the special subject which I touch on in the part which will come out now in April. Please write and tell me if you or other people find any.

You are right that War and Peace grows in my eyes. I have a strange feeling of joy when people remind me of something from it as Istomin did recently (he’ll be staying with you), but it’s strange, I remember very few passages from it, and the rest I forget.

Goodbye; a thousand thanks once more. I still hope to finish. But I shall hardly have the strength. In summer I often feel the physical impossibility of writing.

Yours,

L. Tolstoy

FURTHER READING

Leo Tolstoy and Nikolai Strakhov remained close friends throughout their lives, rallying around similar slavophilic philosophies and cultural tastes. To delve further into this fruitful friendship, read here

Read here for a film review describing shortcomings Joe Wright’s recent adaptation of Anna Karenina

For a gloss of the Tolstoyan ghost in Nabokov’s Laughter in the Dark, look no further than here