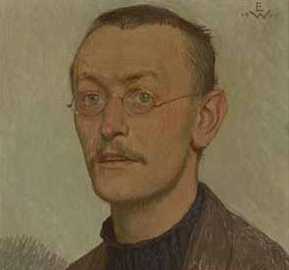

Hermann Hesse won the Nobel Prize in 1946; thereafter, he spent the majority of his time letter-writing, estimating that his daily correspondence occupied some 150 manuscript pages. Below, Hesse responds to a letter by Felix Lützkendorf, who had written a dissertation on his work in the early 1930s.

To Felix Lützkendorf

October 25, 1946

I’m heading off tomorrow for a sanatorium, and my house will remain empty for several months at least. First, I want to thank you for your letter of October 10. It arrived at the same time as a letter from Thomas Mann, in which he says in his own way much the same things about the German mentality as I have been saying in mine, and your comments about your former colleagues in Germanistics provide further confirmation.

No, on the whole I don’t expect anything good to come out of Germany, and never have. The rest of the world, which it had wanted to rape and dominate, is now finding Germany thoroughly indigestible, in intellectual terms as well. But I feel that the world is comprised not of nations but of people, and as far as people go, there are still many worthwhile individuals in your country. Even though I have been living outside Germany for thirty-four years now, I know a few dozen of them, and would rank them among the best anywhere. They are the ones who matter, it seems to me, especially their ability to work on the masses like salt and leaven and keep them under control. Here I am thinking far more of the intellectual and moral life than actual political action.

I have been less taken up with the denunciatory letters that have come my way over the past months than with the various honors. Hesse evenings are being held in a series of cities and towns, talks as well; I receive copies of the formal addresses. Then there was the Goethe Prize, and Calw, my hometown, is producing a Hesse selection in two volumes, just those writings dealing with Calw and Swabia. Almost all of this is a burden, I find, what with the new letters, questions, misunderstandings, often also respectful letters from people who just yesterday still believed in the opposite. And I regard my utter inability to relate to this whole business as a sign that I have lived differently from most people, and relied almost entirely on my own resources, had no fatherland, no like-minded souls around me, no sense of community. I had roots in a homeland, but it was not close by, or even in the present era; my fatherland was called Castalia, and I discerned my saints and kings in the old Indians and Chinese, etc.

I shall feel disappointed and somewhat bitter as I die, but only in regard to my person, my private sphere, and the way I was embedded in the world. I have had to work for a people that reacts either with sentimentality and reverence or with animal-like brutality. Because of the language into which I was born, I have had to entrust my life’s work to that people, and now feel disappointed and cheated. But taken as a whole and in a higher sense, my life and work have certainly been meaningful, and whatever is left of my work will survive. So, to that extent, I am not ending in bankruptcy.

My present relationship to the Germans is subject to all sorts of strange overlappings and sudden changes. For instance, some political friends of mine, who were proven martyrs under Hitler, have drifted away from me and I have been disappointed in them, whereas several former fellow travelers under Hitler have already won me over by means of a pure confession and repentance.

My next address is: c/o Dr. O. Riggenback in Marin near Neuchâtel. If possible, pass this on to Suhrkamp as well.

Enough. I haven’t written this long a letter for months, and shall not be able to do so again for some time.