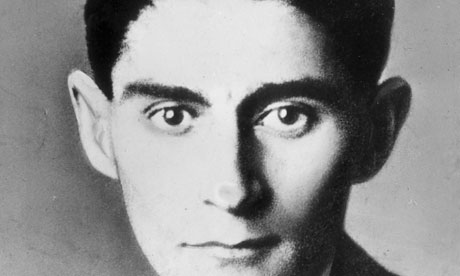

Franz Kafka

Franz Kafka

After he was diagnosed with tuberculosis in August of 1917, Franz Kafka moved to the Bohemian village of Zürau, where he kept a small and humble house with his sister, Ottla. Below, he writes best friend (and, of course, eventual literary executor) Max Brod about his first impressions of the place. (NB: Again, we cheat a bit here. The letter is dated only to “mid-September, 1917.” It did, however, seem worth a slight shirking of the governing constraint.)

TO MAX BROD

mid-September 1917, Zürau

Dear Max,

The exquisite instinct you and I both have! A vulture, seeking quiet, I fly upward and swoop, straight as a die, into this room, opposite which a piano, wildly thumping its pedals, is playing, surely the only piano in this whole region. But I toss it, unfortunately only figuratively, into the mix, along with the many good things that have come my way here.

Our correspondence can be very simple: I do my writing, you yours, and that is answer, verdict, consolation, inconsolability, whatever one likes. For it is the same knife against whose blade our throats, our poor pigeons’ throats, one here, on there, are cut. But so slowly, so insidiously, with so little blood, so heartrendingly, so hearts-rendingly.

In this context the morality is perhaps the last consideration, not even the last, the blood is the first and the second and the last. The question is how much passion is there, how much time it will take, for the walls of the heart to be pounded thin, that is if the lungs do not give out before the heart.

F. has sent a few lines saying she is coming. I don’t grasp her, she is extraordinary, or rather I do grasp her but cannot hold her. I run all around her, barking, as a nervous dog might tear around a statue, or to present an equally true but converse picture, I gaze at her as a stuffed animal head mounted on the wall might look down on the person living quietly in his room. Half-truths, a thousandth of a truth. All that is true is that F. is probably coming.

So many things trouble me, I can find no way out. Was it false hope, self-deception, when I told myself I wanted to stay here forever, I mean in the country, far from the railroad, near the relentless twilight, which descends without hindrance from anyone or anything. If it is self-deception, then it comes because my blood is tempting me to a reincarnation of my uncle, the country doctor whom I (with all due and indeed the greatest respect) sometimes call the Twitterer, because he has such an inhumanly thin old-bachelor’s birdlike wit that squeaks out of a constricted throat and never deserts him. And he lives this way in the country, won’t be budged from it, contented, the way a faintly burbling madness which one takes for the melody of life leads to contentment. But if the longing for the land is not self-deception, then it is something good. But have I the right to expect something good, at the age of thirty-four, with my highly fragile lungs and still more fragile human relationships. Country doctor is more probable; if you look for confirmation, the father’s curse is there at once. Lovely nocturnal sight when hope wrestles with the Father.

Let’s drop the wrestlers. The plans you have for your novella are exactly what I would wish. The novella is going to be splendid. But in the face of these plans, can the first two chapters stand? They are after all too lightweight. To my feeling, not at all. What are those three pages like, that you have written? Do they decide anything for the whole? Is it painful that the whole thing will refute Tycho? It will not refute it since all truth is irrefutable, though it may throw him down. But as all the war correspondents write, isn’t the best assault technique still: stand up, run, throw yourself down? A procedure that must be incessantly repeated in the assault upon the tremendous bastion, until in the last volume of the Collected Works, blissfully weary, one drops or—with worse luck—remains on one’s knees.

I do not mean this sadly. Nor am I basically sad. I live with Ottla in a good minor marriage; marriage not on the basis of the usual violent high currents but of the small windings of the low voltages. We run a fine household, which all of you, I hope, will like. I will try to put some supplies aside for you, Felix, and Oskar, which isn’t easy; there is not much food around here and the many family mouths to feed have priority. But there is always something, which however everyone must procure in person.

As for my sickness—I have no fever. Weight on arrival was 6½ kilos but I have already put on a little. Beautiful weather. Been lying in the sun a good deal. At the moment do not miss Switzerland; in any case your news from there can only be badly dated.

All the best and may Heaven shower some comforts on you.

Franz

[IN THE MARGIN]

Should you need help with letters, I could easily ask my typist.

I imagine you have already received a letter from me. Letters take three or four days one way.

+

FURTHER READING

For more on “F.”, click here and here.

For more on the Kafka/Brod relationship (as well as some of the insanity surrounding the legal fate of Kafka’s papers after Brod’s death), click here and here.