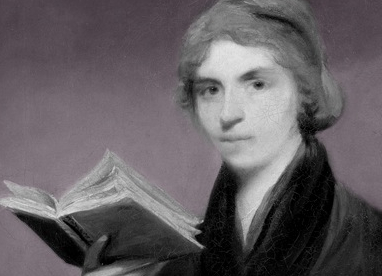

Joseph Johnson was a London-based bookseller and publisher famous (notorious) for printing the work of intellectual ‘radicals’ such as William Godwin, Joseph Priestly, William Blake (whom he employed, occasionally, as an engraver) and Mary Wollstonecraft. Below, Wollstonecraft writes to Johnson regarding her lingering fondness for former pupil, Margaret King; her attempt to translate an Italian MS. while knowing only rudimentary Italian; and her thoughts on Johnson’s objections to the (stern, insistent) preface she had written for her Original Stories from Real Life, a collection of tales for children. In the preface, Wollstonecraft had argued that children should be taught by example rather than precept, adding: “But to wish that parents would, themselves, mould the ductile passions, is a chimerical wish, for the present generation have their own passions to combat with and fastidious pleasures to pursue, neglecting those pointed out by nature: we must therefore pour premature knowledge into the succeeding one; and, teaching virtue, explain the nature of vice. Cruel necessity.”

TO JOSEPH JOHNSON

December, 1787, London

My dear sir,

Though your remarks are generally judicious—I cannot now concur with you, I mean with respect to the preface, and have not altered it. I hate the usual smooth way of exhibiting proud humility. A general rule only extends to the majority—and, believe me, the few judicious parents who may peruse my book, will not feel themselves hurt—and the weak are too vain to mind what is said in a book intended for children.

I return you the Italian MS.—but do not hastily imagine that I am indolent. I would not spare any labour to do my duty—and, after the most laborious day, that single thought would solace me more than any pleasures the senses could enjoy. I find I could not translate the MS. well. If it was not a MS, I should not be so easily intimidated; but the hand, and errors in orthography, or abbreviations, are a stumbling-block at the first setting out.—I cannot bear to do any thing I cannot do well—and I should lose time in the vain attempt.

I had, the other day, the satisfaction of again receiving a letter from my poor, dear Margaret.—With all a mother’s fondness I could transcribe a part of it—She says, every day her affection to me, and dependence on heaven increase, &c.—I miss her innocent caresses—and sometimes indulge a pleasing hope, that she may be allowed to cheer my childless age—if I am to live to be old.—At any rate, I may hear of the virtues I may not contemplate—and my reason may permit me to love a female.—I now allude to ——-. I have received another letter from her, and her childish complaints vex me—indeed they do—As usual, good-night.

Mary.

If parents attended to their children, I would not have written the stories; for, what are books—compared to conversations which affection inforces!—

+

FURTHER READING

For the full text of Wollstonecraft’s Original Stories from Real Life: with conversations, calculated to regulate the affections, and form the mind to truth and goodness, click here.

For more on Johnson’s publishing ventures and political radicalism, click here.