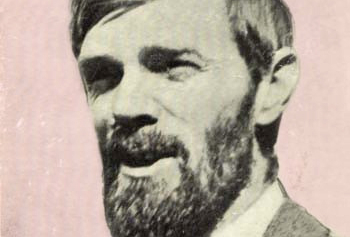

In The Fantasia of the Unconscious, D.H. Lawrence wrote: “Remember, dear reader, that there is not the slightest need for you to believe me, or even read me.” Lawrence held the masses in low esteem, which is why many of his love scenes take place in the wilderness, far from the community of city or town. His fervent search for an authentic point of connection led to a distaste for the reading public, although he never, even at his most isolated, stopped writing to an audience. In the following letter, Lawrence wrestles with the unease he felt towards humanity as a whole, declaring a “war” which would last until his death in 1930.

To Gordon Campbell, 23 December 1916

Zennor, St. Ives, Cornwall

23 Dec. 1916

My dear Campbell,

I was glad to hear from you, but your letter was not a happy one. I read Murry’s novel in MS, and thought it just wasn’t a book at all: statement, not created. I am afraid he is not a creative artist in any sense. Where it looks like creation, it is replica. —I am glad you didn’t write your novel, really, if it was going to be at all like Murry’s. What I can’t stand about him is his central conceit. He wants to be, in his own ideal, equal with the best and greatest of men: Tolstoy or Dostoevsky or whosoever it may be: he is utterly unwilling to take himself for what he is, a clever, but unoriginal, non-creative individual. He never has a new thought: he is very clever arranger of given thoughts, making new combinations of given terms…I dislike him that he must assume himself the equal of the highest. That is the very essence of his malady, and all his twist and struggle is to make this falsehood appear a truth to himself. There is a ghastly feeling in the country. I never felt so sick as I do now with the ugly spirit that pervades everything. It is loathsome that this is Christmas. But the coming year will see the collapse of a great deal of us, and I hope we shall be able to begin something new. One always hopes and hopes for this. […]

I don’t know what will happen to us—it doesn’t seem to matter much. I feel all right in myself: it is the social part of me that feels dragged down. My individual self is all right, but it seems quite cut off and isolated, as if it had no connection and no relation with anybody, beyond Frieda. It is all right for myself: that side of myself which is single is fulfilled and happy. But there is a gnawing craving in oneself, to move and live not only as a single, satisfied individual, but as a real representative of the whole race. I am a pure self, and fulfilled in that. But I have no connection with the rest of people, I am only at war with them, at war with the whole body of mankind. And to be isolated in resistance against the whole body of mankind isn’t right. But it will alter, when the existing frame smashes, as it must smash directly.

I hope one day we shall be in accord, you and I, and do some sort of work together. Kindest regards to you all from Frieda and me.

Yours,

D.H. Lawrence

Notes: John Middleton Murry, best known for his critical work on Fyodor Dostoevsky and John Keats, published his first work of fiction in 1916. The novel Still Life was met with resounding scorn from critics and friends alike for its weighty style and explicitly autobiographical content. Murry admitted post-publication that it was his own “blundering way of learning.”

From The Letters of D.H. Lawrence, Vol. 3. Ed. James T. Boulton and Andrew Robertson. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

FURTHER READING

Full text of The Fantasia of the Unconscious, described by Linda Ruth Williams as “a highly systematized but certifiable schizo-rant”.

A centennial tribute to Sons and Lovers with full account of its current critical standing.

The Lawrence hub at the University of Nottingham.