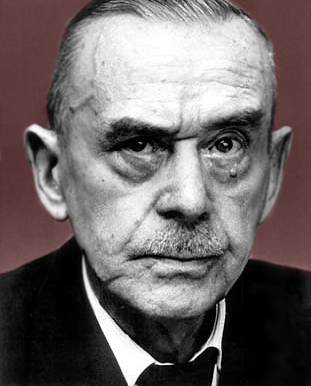

In a letter to the writer Hans Friedrich Blunck, whose work for various Nazi cultural institutions included founding an organization devoted to building a positive image of the Third Reich in other countries, Thomas Mann condemns the German intelligentsia for failing to stand against Nazism.

Pacific Palisades

July 22, 1946

My dear Herr Blunck:

“Consternation” is the only word I can use to describe the feeling with which I read your letter and memorandum. They are not the only ones of their kind; why am I the recipient of these reports, declarations, justifications from Germany? I do not have the power to bind and loose, you know. And if I am taken as representative of the “world,” why, this world is currently behaving so inadequately that one hardly needs to make apologies to it. Everyone must try to settle with his own conscience.

My comment on you was quite by the way, not voluntary, but elicited by your brother’s letter. I could only reply that it would look strange for me, who so ostentatiously turned my back on the Third Reich, if I were not to allow my name to be used to influence the Occupation authorities in favor of a literary spokesman and dignitary of that Reich.

You maintain that you were nothing of the kind, and I do not want to class this argument with the general phenomenon that nowadays everybody insists that he “wasn’t.” But when I read such sentences in your statement as: “When Hitler in 1933 was called to the chancellorship by President von Hindenburg and took the oath of loyalty to the Weimar Constitution, I trusted the solemn declarations that all citizens would have the same rights. I assumed that a brief period of transition to a new constitution was involved….After the death of Rudolf Bending I was invited to take a seat in the German Academy in Munich. My activity was limited to…offering advice and proposals for instruction in the German language abroad—” when I read such things I can only lift my eyes to heaven and say: “Almighty God!” Is so much blindness possible? Can any intellectual have so completely lacked insight and feeling for the horror that was going on? Did Hitler’s magic consist in his ability to make people believe he would be the protector of the Weimar Constitution? Before he issued a new constitution? And the “instruction in the German language abroad”! Every child in the whole wide world knew what was meant by this euphemism, namely the undermining of the democratic forces of resistance everywhere, their demoralization by Nazi propaganda. Only the German writer did not know. He had no problem; he could be a purehearted simpleton and cultivate a placid temper, without moral indignation, without any capacity for detestation, for anger, for horror at the altogether infamous Teufelsdreck [devil’s dung] which National Socialism was to every decent soul from the first day on.

And you were invited to be a member of the Nazi Academy in Munich. Now just imagine: to my way of thinking, no colleague should ever have been willing to take the seat from which I was expelled in the most offensive manner immediately after Hitler took his “oath to the Weimar Constitution.” Does that strike you as very conceited? But I do not stand alone in holding this view. It is shared by the entire intelligentsia. Only in Germany do people lack any feeling for such solidarity, any sense of pride, any courage to protest and take a stand. There they are only too ready to take the side of arrant evil—as long as it looks as if “history” were going to prove the evil right. But a man of letters, a creative writer, ought to know that although life allows all sorts of things, it stops short at absolute immorality.

This letter is degenerating into a philippic, which was the last thing I had in mind. I am scarcely qualified to be a rigid judge of ethics; I am the last to cast a stone and do not in the least regard myself as an authority before whom motions for acquittal should be brought. But nothing can ever dispel my grief and shame at the horrible heartless and brainless failure of the German intelligentsia to meet the test with which it was confronted in 1933. It will have to achieve many glories before that can be forgotten. May God grant it the strength and inner freedom to do so. This is both my general hope and at the same time a very personal wish for your work and future happiness.

FURTHER READING

To hear a 1940 radio clip of Thomas Mann denouncing the effects of anti-Semitism on democracy, click here.

On being awarded the Nobel Prize for literature in 1929, Mann described the grace of German art in the midst of political suffering as an example of “sublime heroism.” To read the full address, click here.