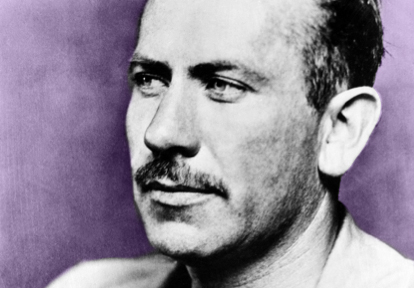

John Steinbeck writes to literary critic Eugène Vinaver to complain about the feel of modern metal pens and to theorize about debauchery in nunneries. Steinbeck was then working on what would eventually become The Acts of King Arthur and His Noble Knights.

My dear Eugène:

Sometimes I simply want to talk to you, and not having you here, a letter is the next best. I do feel that I much impose on your time, so taken with your work and midge-bitten with undergraduates.

It is my custom, before going to work in the morning, to do some writing, much like an athlete warming his muscles for a match. This I have always done—sometimes notes and sometimes letters. But please to remember, they are not traps for answers.

I always write by hand and my fingers are very sensitive to shapes and textures. Modern pencils and pens are too thick and ill-balanced, and you will understand that five to eight hours a day, holding the instrument can make this very important. The wing quill of the goose is the best for weight and balance, curve and the texture of the quill is not foreign to the touch like metal or plastics. Therefore I mount the best fillers from ball points in the stem of the quill and thus have, for me, the best of all writing instruments. When I find some particularly fine quills I will send you one. Besides, some of the finest writing has been done with a quill. For a time I cut my pens but I don’t like the scratching sound. No, this is best and I will like making one for you but I must find a perfect feather from a grandfather goose.

I’m afraid I have fallen a little afoul of the publishing end. Sending some copy to New York I have aroused disappointment. I think they expected something like T. H. White, whose work I admire very much but it is not what I am trying to do.

I am working now on Morgan Le Fay—and the plot against Arthur’s life—one of the most fascinating parts. And, while it may seem to be magic, it is based on a stern reality. Morgan learned necromancy in a nunnery. What better school for witches—lone, unfulfilled women living together. We can conjecture what must have happened in such places but we don’t have to. In my notes I have a number of charges after visitations by inspecting bishops, charges not only of sexual abnormalities but also several demanding the study of magic and necromancy and the celebrations of obscene rites. There were definite reasons for locking the covers of the fonts.

So much to do and think about. A day is ill-equipped with hours. I have been happily digging in the foundations of one of the five cottages of Discove Manor of which the one we live in is the last remaining. I believe that Discove was a Roman religious center, possibly dedicated to Dis Pater and perhaps built on an older ring. Now I know how cottages were built and still are. When a structure burned or was destroyed in war, the stones and bricks and tiles were taken to build something else. Just picking in the foundation of the burned cottage and quite casually, I have found bricks from five different periods, some hardly burned through and some hard, thin, and red, possibly Roman. A hearthstone, coated with modern (last hundred years) cement, when I chipped the coating off, was a shaped stone with just a hint of shallow inscription. Drops of glass, raindrop-shaped, the result of fire but not this recent fire, since they were below the foundation level. Curious stones, some with marine shells and fossils. And these just with my fingers. And when I go down deep—who knows what I shall find? It makes my mind squirm with delight just to think of it.

Now I have done what we call in America bending your ear. I’ve taken enough of your time.

Love to Betty from both of us. Elaine says she is writing to her.

Yours,

John