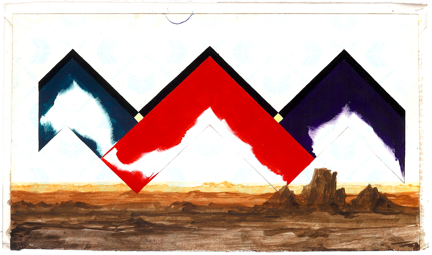

“Untitled (C-34). Erik Schoonebeek.”

1) Poetry, my brother tells me, is too human for him. When he reads poetry he always feels like he’s missing something. Communication is very difficult for me, he tells me.

2) We are talking tonight about the lives we live with art. I bring up one of his paintings, Untitled (C-34), a work composed on the torn-off front cover of a clothbound book, and I think: so it’s deserted. Like a crime scene. And then I hear Walter Benjamin: all efforts to render politics aesthetic, he says—they culminate in one thing: war.

3) I wonder what happens to my brother when he faces a white page filled with poetry. Does he feel the words are rising up against him? Is there longing? I build myself a scenario: my brother is speaking to me in the language we speak every day. I recognize his words and hear them inside my head, but I can’t say what he’s trying to tell me. I tarry a moment inside this unsettlement.

4) And so it was time once again to ask questions of art and a few Americans who make it. Poetry, my brother tells me, is too human for him, so I began by asking my brother’s painting.

5)

| A POET: | What happens to me when I face you? |

| A PAINTING: | Yes you feel sad for me that I’m empty. |

| A POET: | But there’s mountains inside of you. |

| A PAINTING: | You know those old linen postcards—the ones with, I don’t know, the Empire State Building inside of them—where no one is present, where nothing is present save the monument the work glorifies? |

| A POET: | Yes? |

| A PAINTING: |

You’re feeling that way about me. There’s an America you no longer recognize inside of me. |

| A POET: | So what are you trying to tell me about America? |

| A PAINTING: | The question is not tell you the question is I am here will you confront me. |

| A POET: | Yes? |

| A PAINTING: |

I’m intruded upon by three shapes they are dark and bright at once and do they want to call themselves mountains, you wonder. And do they want to confront me the way I’m confronting them now. |

6) A man and a woman are shouting at each other outside in the street. And remember, Don DeLillo tells me. War is just another form of longing.

7)

| A POET: | And do you read poetry? |

| A MUSICIAN: | I do not. |

| A POET: | And why don’t you read poetry? |

| A MUSICIAN: | Well I wouldn’t know what I like. |

8) I wonder if we haven’t, in the last fifteen years, begun the work of turning language into a ritual against loss. When we perform language—as we perform rituals as commonplace as brushing our teeth or looking at photographs of our loved ones—I wonder if we haven’t arrived at a point where language is only valuable to us insofar as it makes good on the tasks we expect it to perform. This is what ritual provides us, after all: a return on our investment.

9) Another artist I know, a designer, asks her partner to marry her this summer. Yes, Elizabeth Bishop tells me. Yes, that peculiar affirmative…

10) It’s required of language, for instance, that we can tell someone we want to begin a family with them—yes—or order our children food by putting language to work. Likewise, it’s the job of language to tell people our status and prohibit others from calling us friends. Every day, it’s language that must announce to the world what we like. And I wonder if we don’t expect language to perform this ritual more than any generation before us. Post by post, text by text, send by send, and all within a box provided to us and within 140 characters, the job we demand of language above all others is to carry out our business.

11)

| A POET: | And why don’t you read poetry? |

| AN ILLUSTRATOR: |

I don’t need a million literary devices if they don’t add jack shit to what you’re trying to make me feel. |

12) When I wonder if poetry has dignity, as I do tonight, I wonder if the reason American artists and citizens don’t engage with poetry is because poetry is language that refuses to carry out business.

13) My father, a photographer, asks me what’s new at work. It’s hard, oh it’s hard, William Carlos Williams tells me. It’s hard to get the news from poems.

14) And it’s true: poetry doesn’t arrive on our doorsteps each morning tied snug with twine. But poetry still remains the place to which you can bring yourself to confront the lives of others, which is all the news ever was in the first place.

15) But if people spoke in shapes and colors, my brother tells me, I would work with something other than the visual.

16) I wonder about American culture when my roommate sings in the shower. I wonder about our respect for the arts that refuse to carry out business in far more literal ways than poetry. One cannot perform a minuet in D on the cello in order to file one’s taxes, for instance. Nor can my brother paint me a mountainscape in order to answer my questions.[i] Music and painting, to use two examples, each maintain their mythos because we don’t use the raw materials of these arts in order to live our lives every day. When Chopin comes on the radio, I wonder if the beauty of the music doesn’t go unchallenged because we haven’t had to fire anyone with a piano that day. Nor have we had to fight for a raise in the key of D Minor.

17) Well I don’t understand it, but I love it. I hear several of my relatives utter this phrase while staring at my brother’s paintings in a gallery in Chelsea this summer. Of the twenty-one paintings he shows that night, he sells thirteen. An auspicious solo exhibition, my aunt whispers, in two regards: my brother is speaking the art world’s language, and they are paying him in return for his work.

18) When I visit a gallery, I wonder if the job our culture demands of language isn’t already performed by the gallery. If attendance is our first investment, the gallery makes good on this investment by telling us what art is. It’s simply a matter of what’s hung on the walls. As for the problem of understanding, of knowing what a painting is trying to make us feel and what we like, it’s the job of money to overcome this dilemma. Like war, the purchasing of luxury art is a political act rendered aesthetic via the form of longing. I wonder how we engage the art inside a gallery with luxury pricing. It’s as though the stature of the art in question is already asserted before our arrival. And our job, as it has so passed into our hands in the absence of language, is to bring ourselves to bear upon these works and confront ourselves as we stand before them in white space.

19) Now I want you to think about facing a white page filled with poetry and ask yourself: where does the onus, the burden of work, fall in this instance? Tell me, we say as we stare at the page. Tell me what you’re trying to make me feel.

20) I wonder if poetry is political, as everyone tells me. When my brother reads a poem, I wonder if he feels he’s being asked to risk losing, to risk missing something. I wonder if he feels he can’t engage the language because it won’t perform the ritual against loss that he demands of it. It’s inside this threat that poetry asks us to risk feeling too human, to not know what we like, and to not feel jack shit toward the feeling we’re trying to feel. The result of which demands that we confront our own longing, our own forms of war. And to refuse to engage with poetry as art amounts to rendering a political reality an aesthetic one. I fire my flare gun into the clouds for poetry as I would for any art that challenges me at home in my skin every day. For any art that stands penniless and failed and reminds me that our laws exist in order to undermine us. The news will always exist inside this unsettlement, which is where we confront the longing and loss in the lives of others, which is all the news ever was in the first place.

21) And what about the student of art history who wrote me to say she doesn’t want poetry written about her. Well you’ll choose the goneness now, Eileen Myles tells me. Like bowing your head to love.

[i] For the sake of argument, the author is playing the devil here. He encourages his brother to answer all questions he asks him for the rest of his life by painting mountainscapes.