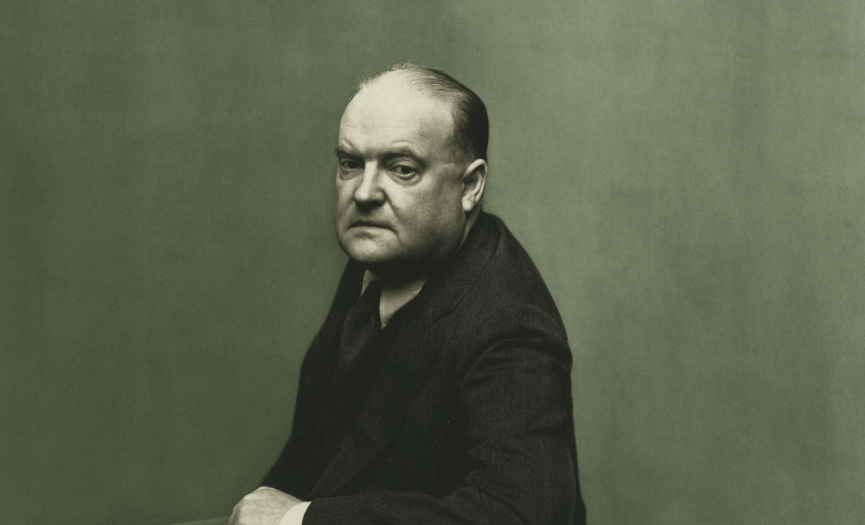

In the letter below, Edmund Wilson writes to John Lester, his former professor, thanking him for his instruction in “the architectonics of prose,” and criticizing the sloppiness of “a good deal of American writing.”

November 20, 1950, Cape Cod

Dear John Lester:

The Hill is celebrating a centenary this year. They have asked me to go there and speak, but it is too far from where I live, and there cannot be anybody I know left there—and in any case I have not had in recent years a very good impression of its standing. So it has occurred to me that the only appropriate thing that I can do to commemorate the occasion is to write to you, as the only survivor of the masters I knew at Hill, in acknowledgement of my great debt to you from my schooldays.

I have thought of you often, and the more I have seen of the inadequate training in English in this country, the more I have appreciated the training you gave us. The work you made us do, for example, in diagramming sentences gave me a grasp of the structure of language which I regard as one of the most valuable things I learned at school, and I can see how the lack of a sense of the architectonics of prose leaves a good deal of American writing so sloppy. I think it is a great advantage, at this stage of one’s education, to be taught English by an Englishman, and I am not sure that things haven’t reached a point where we ought to get teachers from England to teach English as a semi-foreign language, in which students have to be drilled from the ground up. What was remarkable, however, in your courses was the combination of this drill you gave us with a deep appreciation of the literature we were reading and a scholarly attention to the text. Your method of studying the Ancient Mariner still represents for me an ideal of knowing a work of literature inside out, and I have never read it since without thinking of our old classes.

I am struck, in looking back on the Hill, by the amount and the relatively high quality of the literary activity that went on there, and I don’t know that I can quite account for it. It was largely, I suppose, due to you and Rolfe and Bement and the Bavertus, and you people, I suppose, were due to John Meigs—though, as you once later said to me, his ideas on education must have been otherwise rather dim—having set out to equip the Hill with top-notch masters in every department. But it may be that we students were unconsciously taking part in the general literary renascence that was going on in this country at that time. In any case, it seems to me curious to find in the colleges nowadays these composition courses designed to encourage “creative writing.” In our time, we tried to do creative writing outside the college curriculum without any need for such courses and on the basis of the training and stimulus that we got out of the courses in literature. Though Hill did have what seem, as I look back on it, some rather depressing features, a boy with an interest in writing could certainly not, in this country at that time, have gone to any other school that would have given him so much help and inspiration.

I was sorry not to have seen that Exeter and St. Paul’s—both, I should say, inferior to Hill in its best days and both rather old-fashioned—have, in their respective ways, survived and kept up their standards through a long succession of administrations, whereas Hill, so far as I hear, is now more or less second rate. I haven’t been able to make up my mind where to send my son. He is at present a day-scholar (in the Second Form) at St. George’s in Newport, but I am not sure that I want him to finish there. I get the impression that St. George’s, too, is not quite what it used to be. Is there any school at present that you would recommend for a boy who is already developing decided intellectual interests?

In the meantime, I am sending you two books of mind. There is an essay in one of them on Alfred Rolfe. When I first wrote it, I also had you and some of the other masters in it, but decided that it was better to concentrate on a single subject. Your imprint is, however, to be seen in everything I have ever written, for I first learned from you to pay attention to the mechanics of writing and to have some ideal of prose expression. Wasn’t the great message of Buehler’s Rhetoric, cleanness, precision, ease and force?

I hope that you are well and happy. I hear good reports of your son from Harvard. Please remember me to your wife, of whom I have pleasant memories.

Yours as ever, / Edmund Wilson

+